3. LIFE IN THE WRACK FOREST

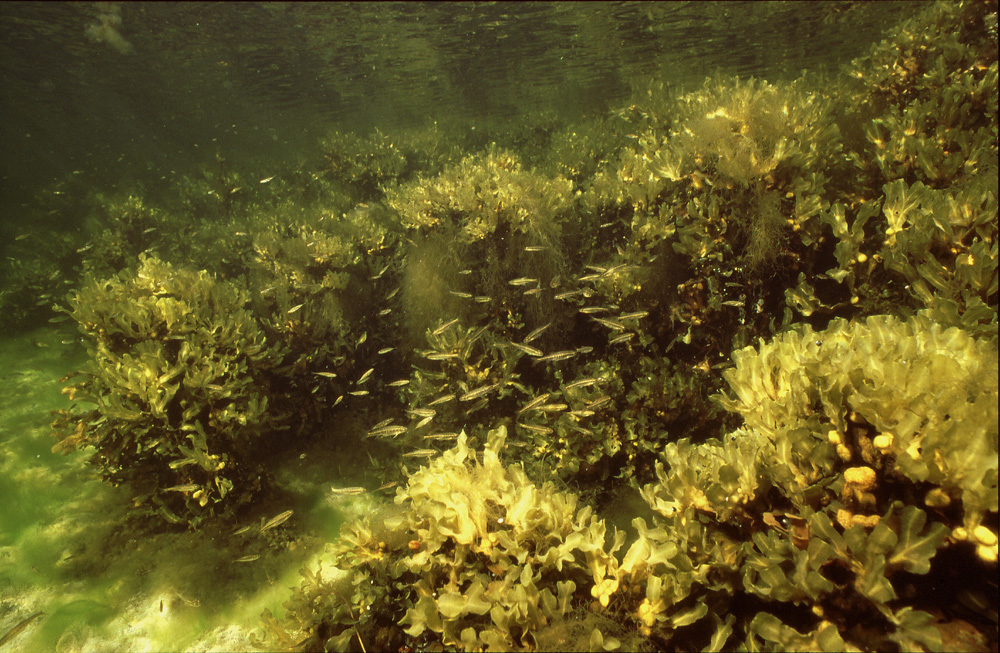

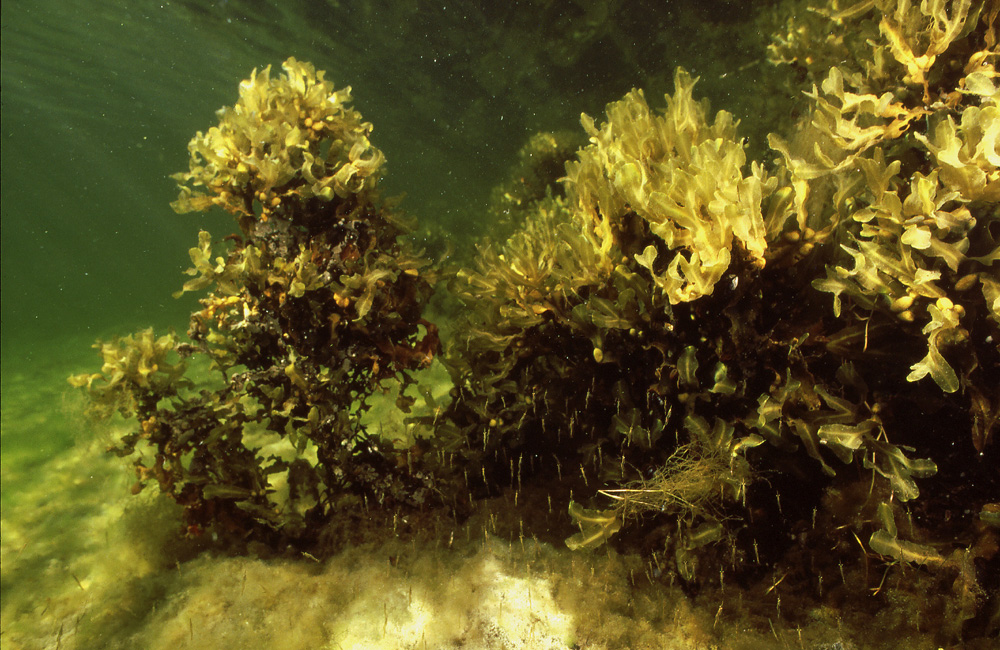

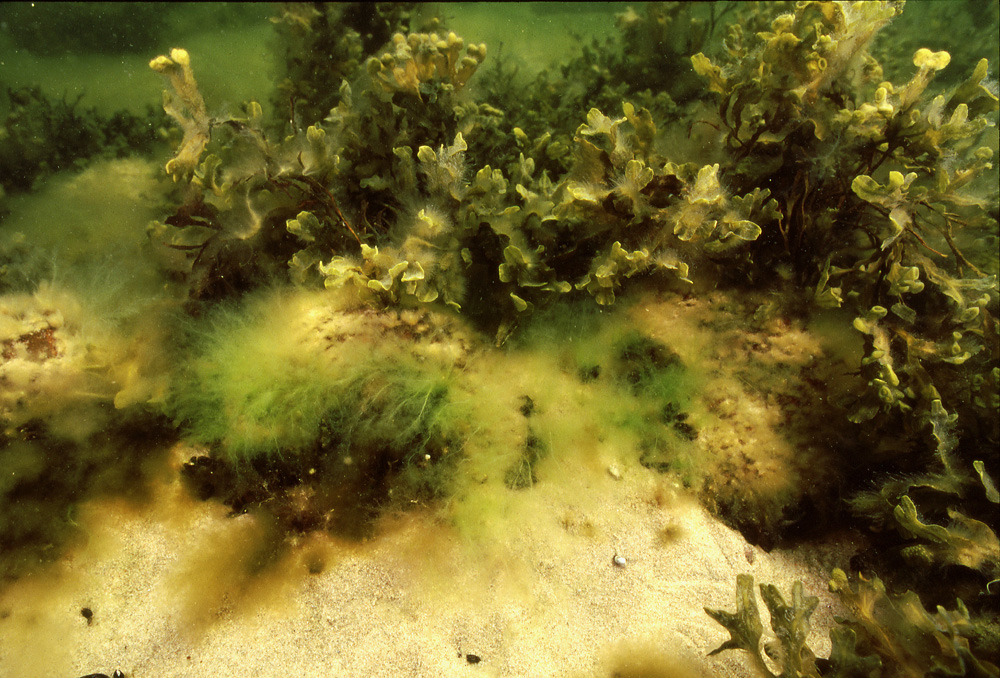

The areas near the shores occupied by bladder wracks are the Baltic counterpart of kelp forests of the oceans. There is a scale difference, though, and while even some larger mammals find shelter within a kelp forest, mostly just the smaller invertebrates of the Baltic will be harbored by the these algal formations.

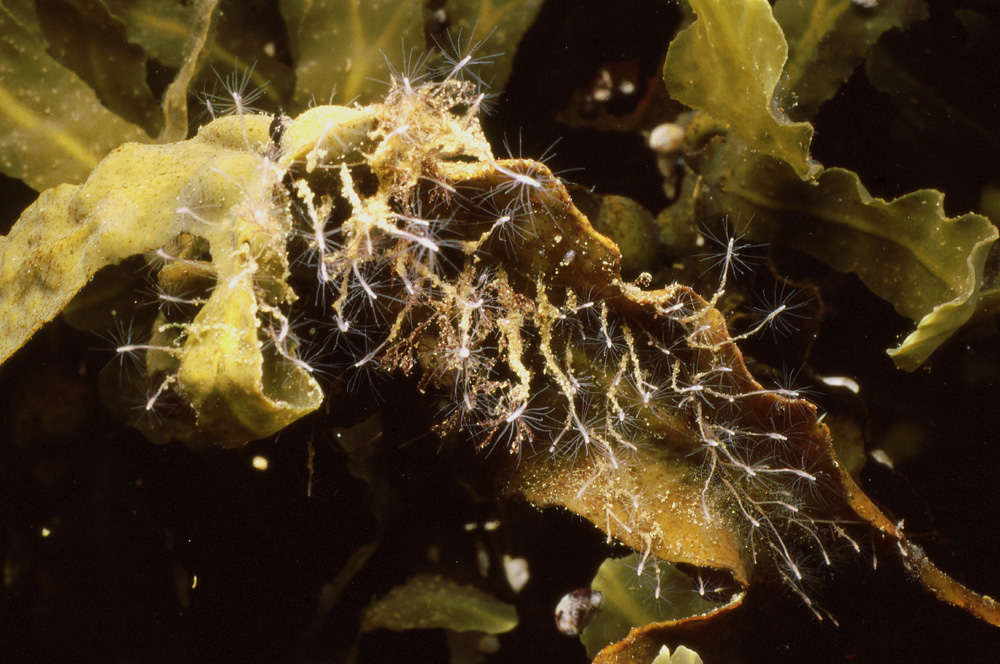

These colonial hydrozoans clearly only thrive in the upper parts of the wrack. When wave conditions are less severe and there is no lack of nutrients in the water, both the laomedea and cordylophora can be abundant.

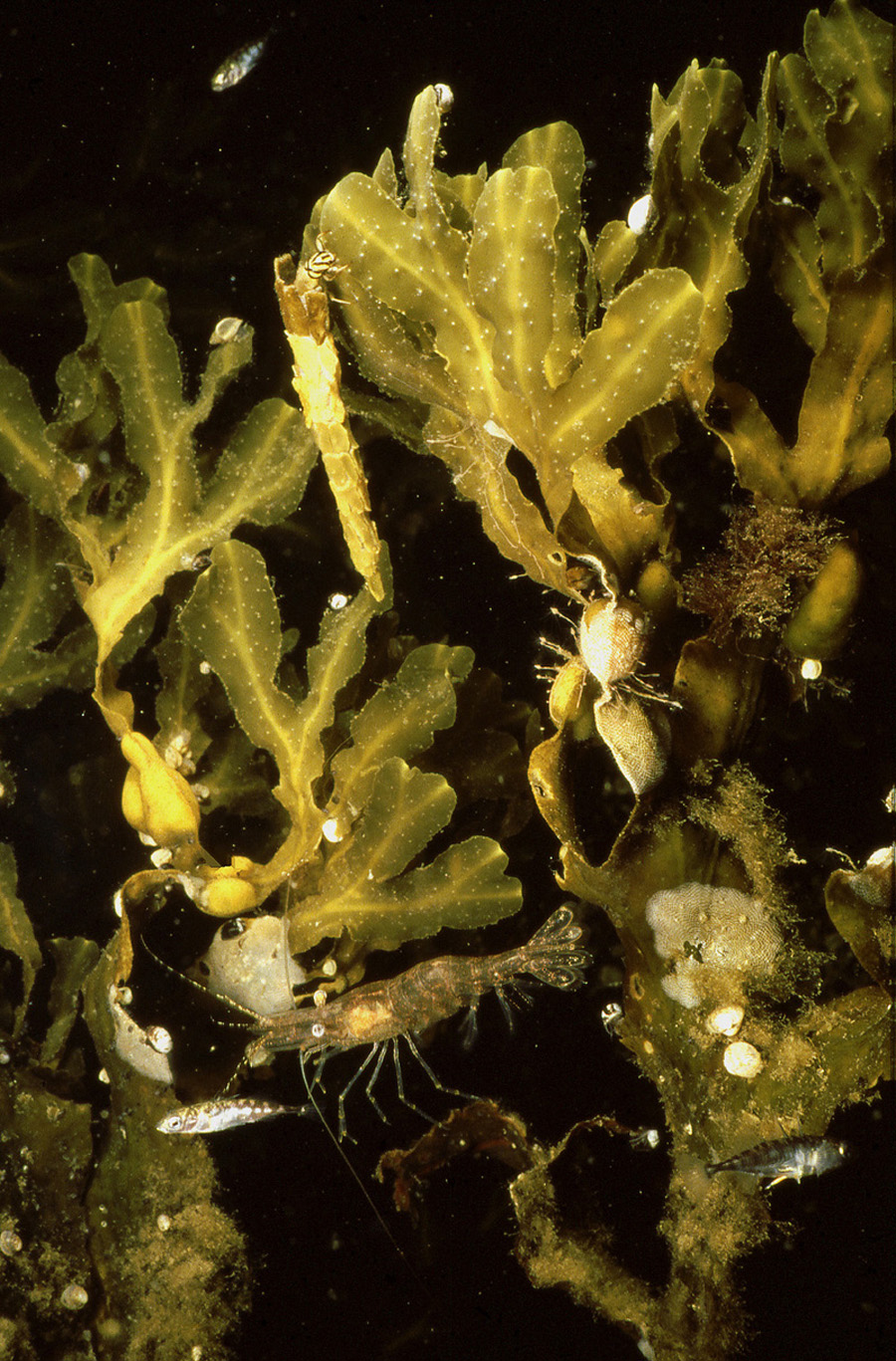

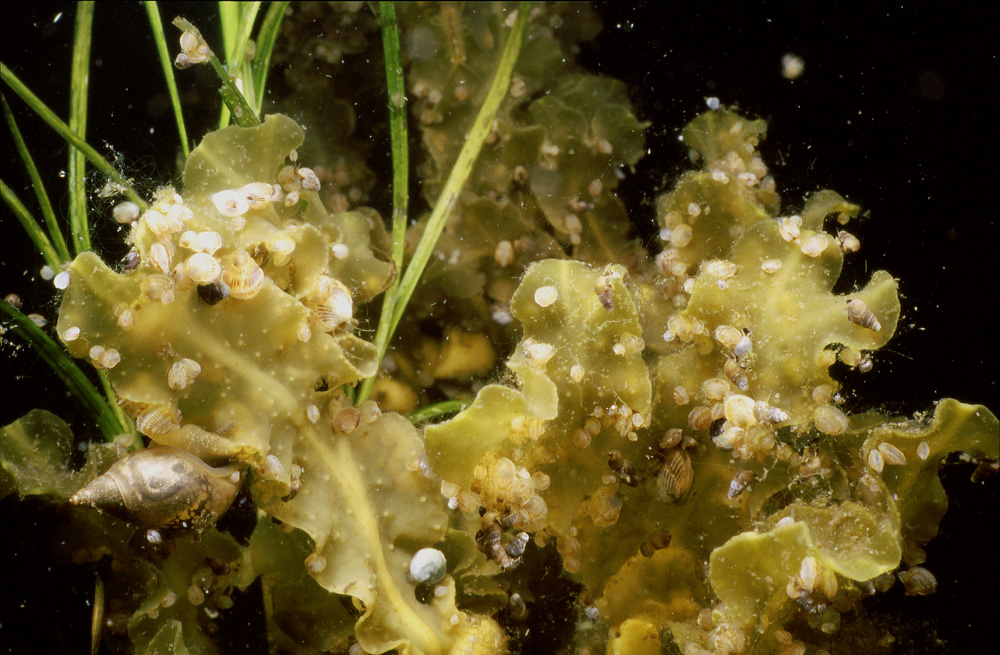

At protected locations, the upper parts of the wrack can also be occupied by motile animals, feeding on organic matter of different kinds. Here there are at least three different species of shells and, possibly, two different cockles.

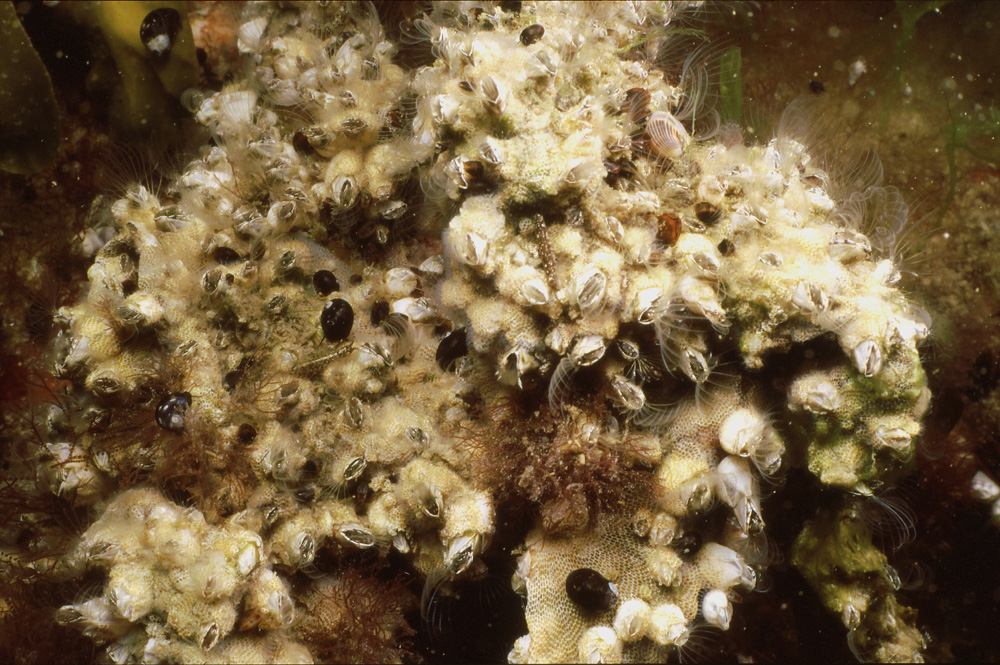

In the more protected lower parts of the alga the sessile colony is dominated by another set of species. Here, bivalves (mostly mussels) and barnacles have overgrown the thalli totally but are covered by the moss animal Electra crustulenta in turn.

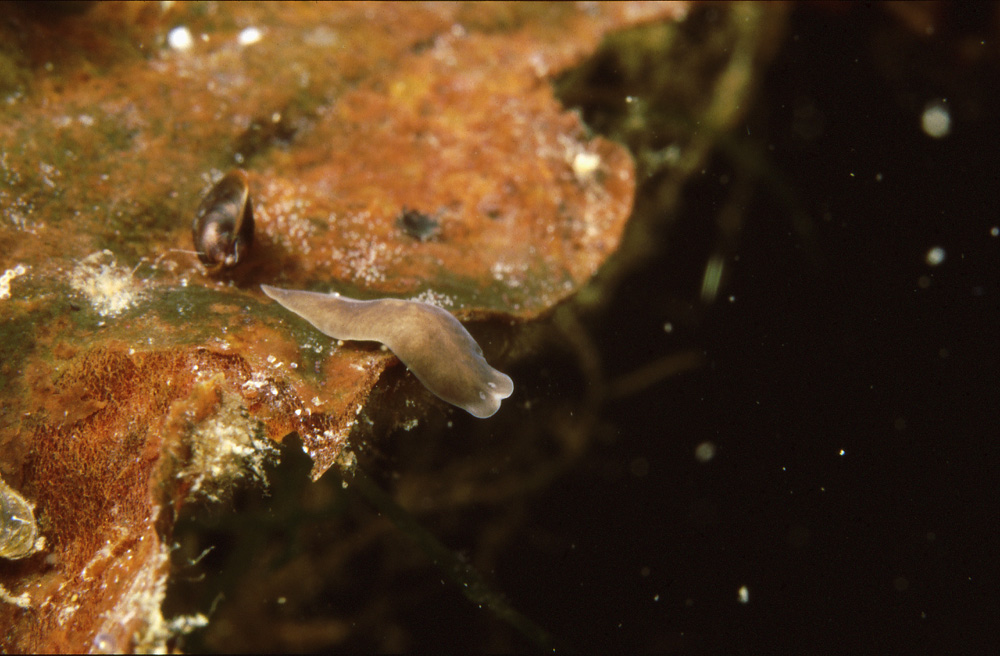

Of the smaller invertebrates creeping on the thalli of the wrack the shells Theodoxus and amphipods Gammarus are usually abundant, the flatworms less so.

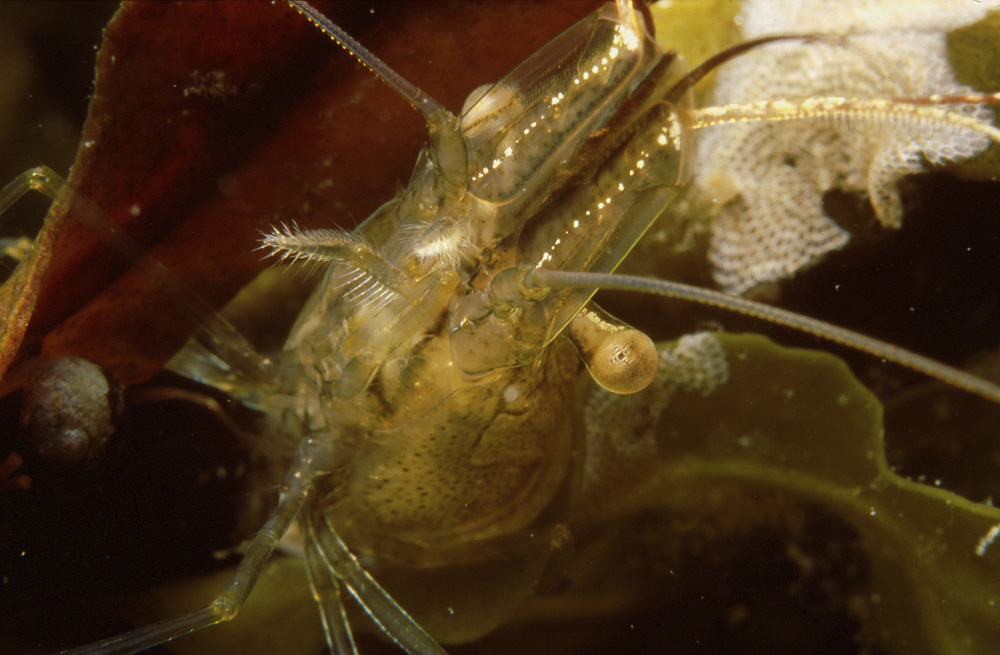

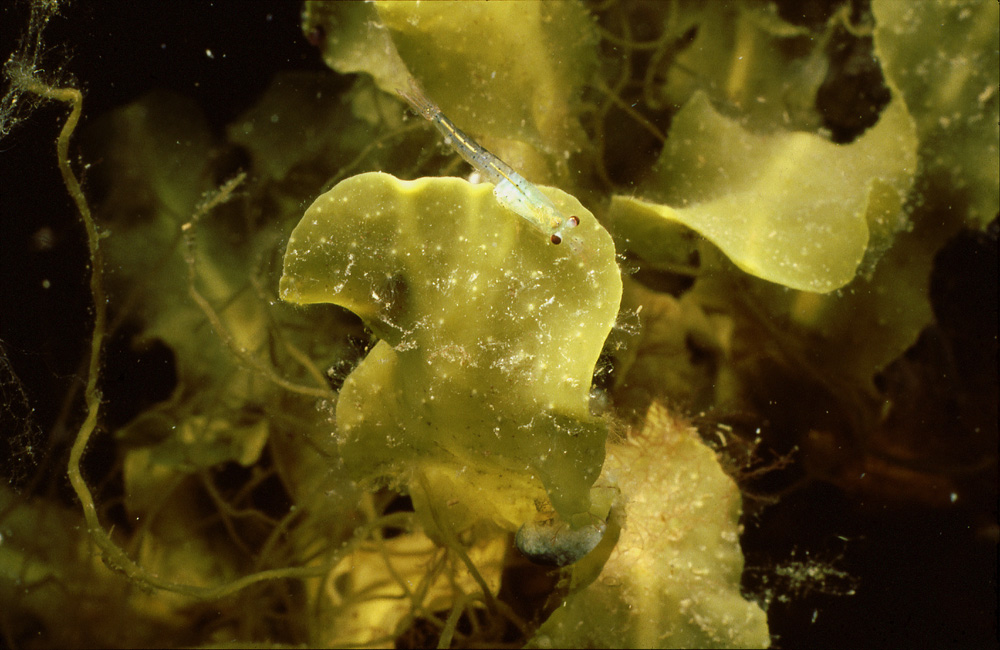

The common shrimp, with its length of about 5 cm, is the largest of the invertebrates hiding on and among the thalli.

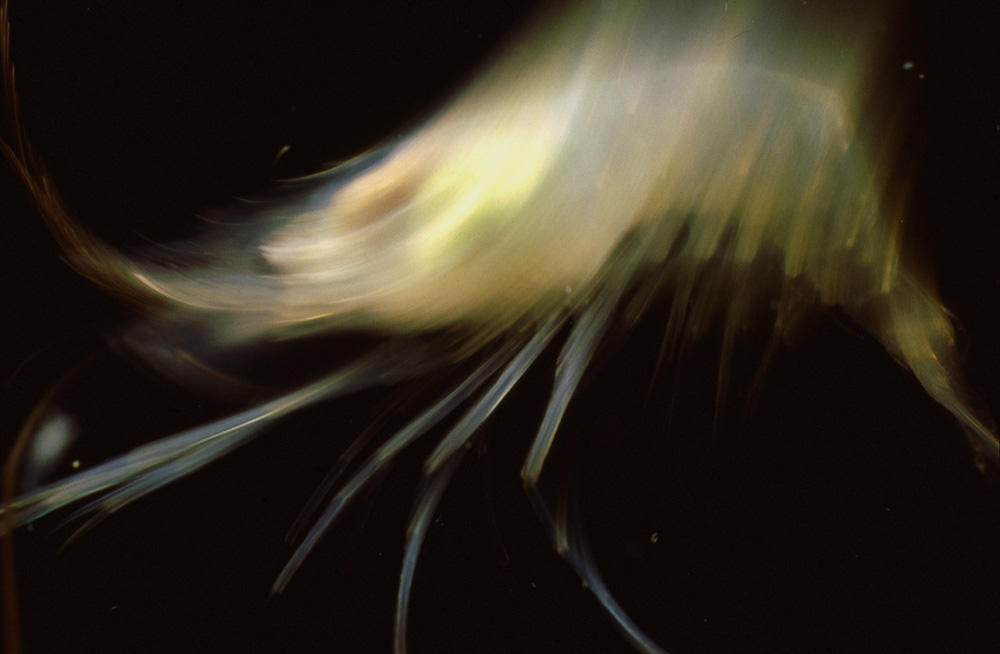

The shrimp swims using the appendages of the abdomen, called pleopods, while the appendages of the thorax, or legs, remain immobile. If startled, the common shrimp, as is typical of the other crustaceans as well, slaps with its posterior body and appendages, called telson, to make a short jump and get out of the danger.

Like all the animals with an exoskeleton the common shrimp has to keep molting, or shedding its exoskeleton, while growing in size.

While her eggs are developing the common shrimp carries them between her pleopods for protection and to create enough flow of water for sufficient oxygen supply.

Two of the three common mysid shrimps in or near the wrack belt belong to the genus Praunus. P. flexuosus is the more abundant and visible one while P. inermis is more elusive and, typically, drops onto the hidden parts of the thalli if disturbed even in the least.

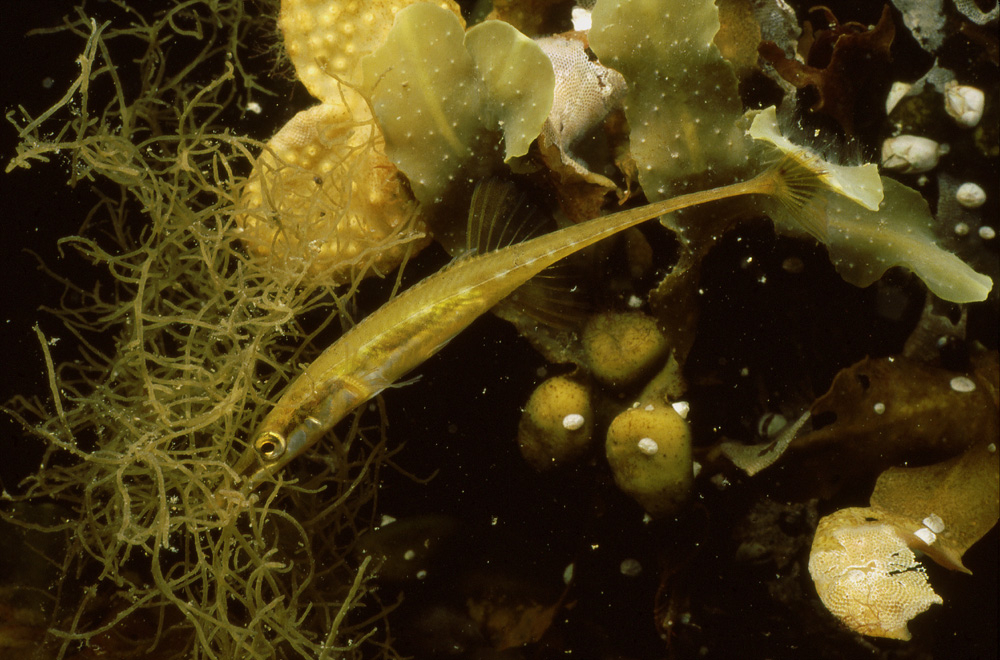

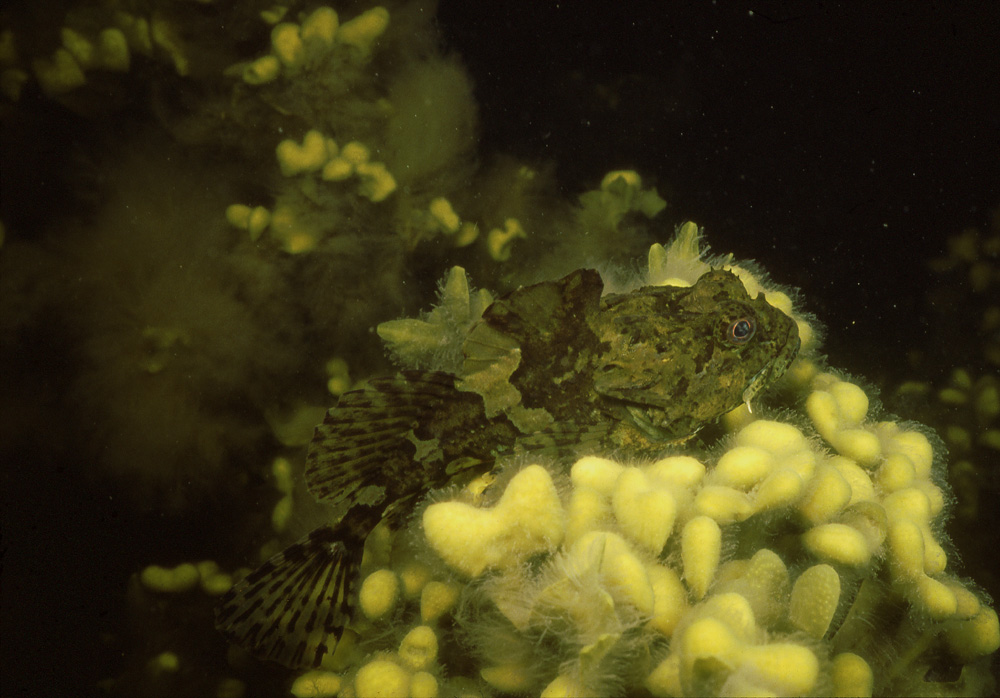

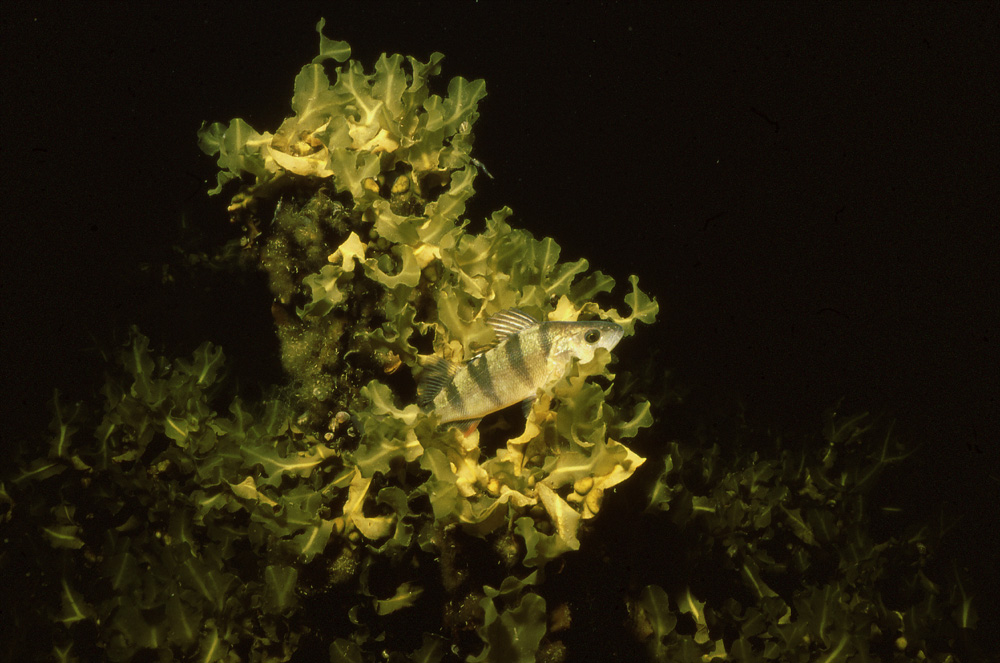

Of all the fishes living in the wrack belt, the life of the fifteen-spined stickleback is the one with the most close intertwining with its surroundings. This species seldom, if ever, leaves the cover of the algae. On this photo you can test its camouflaging ability: the fish is exactly in the middle.

The fifteen-spined stickleback, as far as known, does not live a cycle of full two years. The spring is the time for reproduction for this species, and it is its only chance for it, too. The strategy is to keep mostly hiding among the wracks and, at the same time, look for another fish to mate with.

Like in other species of sticklebacks the male builds a nest using its kidney secretion to bind some vegetation together into a bunch. After luring a female to lay her eggs in the nest the task of the male is to guard the developing offspring.

The fifteen-spined stickleback grows amazingly rapidly: later in summer the young fishes of the year are of the order of ten centimeters long. By then the older generation is thought to be gone already.

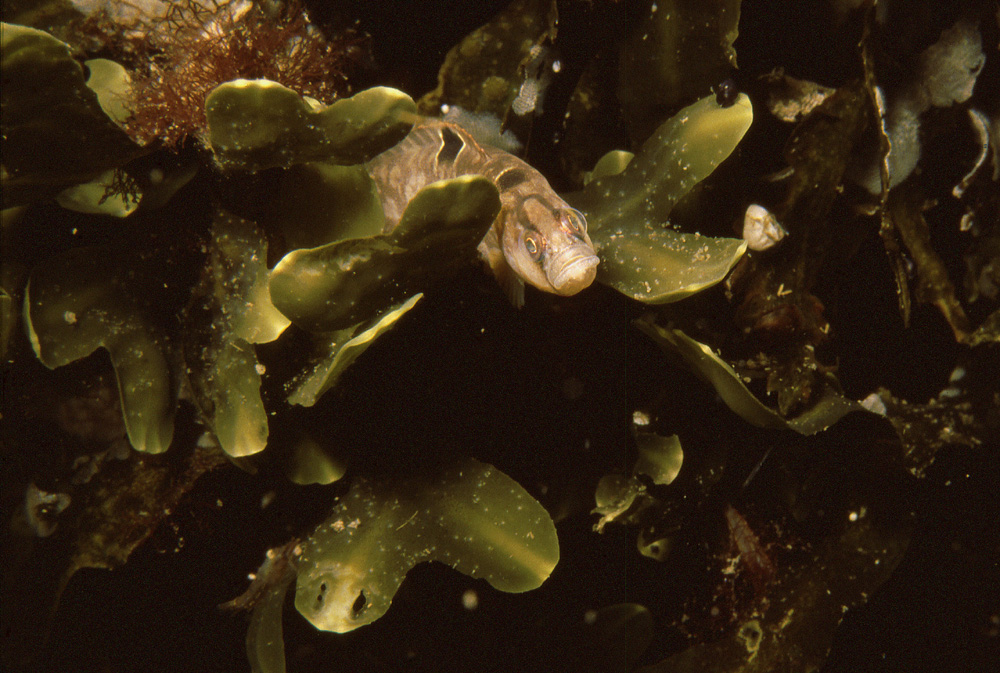

The two-spotted goby hangs around the wrack belt most of the time. It does not seem to actively seek cover among the algae but, rather, its connection is with the mussels growing in the vicinity. It lays its eggs inside empty mussel shells. The male here, resting on the algae sometime in autumn, has already reproduced and, most probably, does not do so anymore.

Some of the occasional visitors into the algae are the scorpion fish, active at night, and the perch, here having its night time nap.

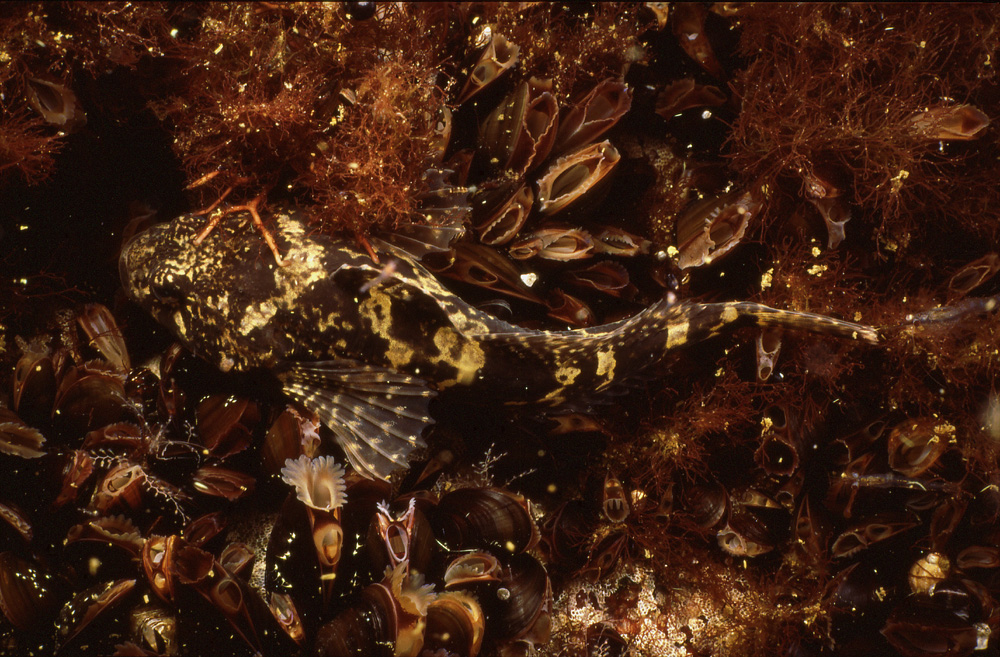

The butterfish leads such an elusive life that it’s difficult to say anything about its abundance in the belt. It is probable, though, that the numbers are low at the moment, just as the sightings in its other living surroundings suggest.

The viviparous blenny is a generalist living in many kinds of surroundings but, just like for the lumpsucker and bullhead, it's the rocks and boulders, found wherever the bladder wrack grows, that it prefers.

For schooling fishes, like the sticklebacks here, the algae are not the only or even the most effective protection against predators: they also tend to seek each other’s company and the cover given by the numbers.

|

Lisää pääkuvan päälle tekstiä klikkaamalla ratas-ikonia,

joka ilmestyy tuodessasi hiiren tämän tekstin päälle.