2. LEADING THE LIFE OF AN ALGA IN THE BALTIC

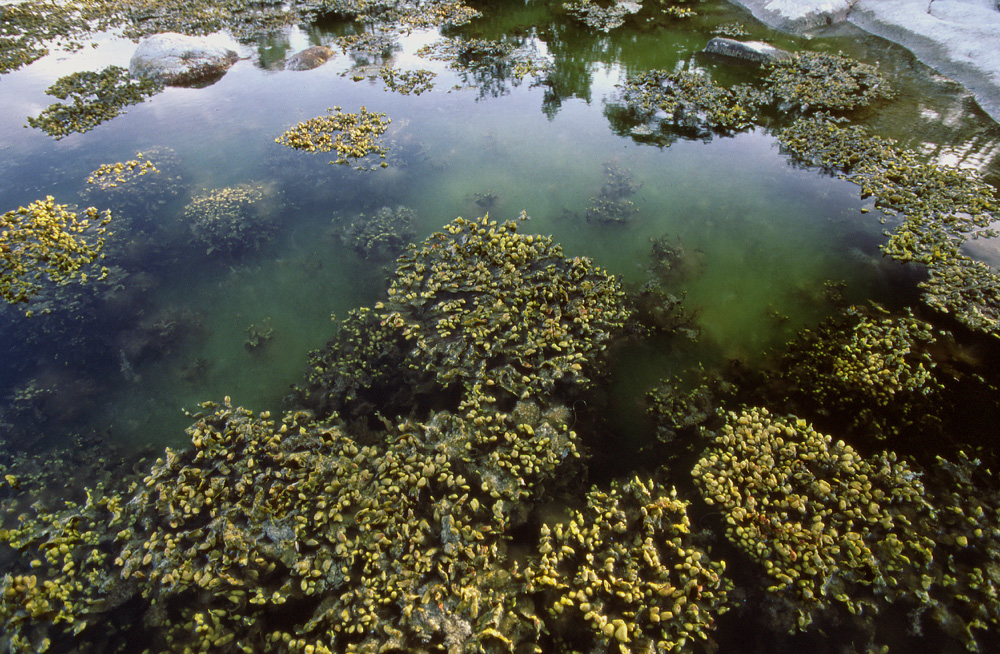

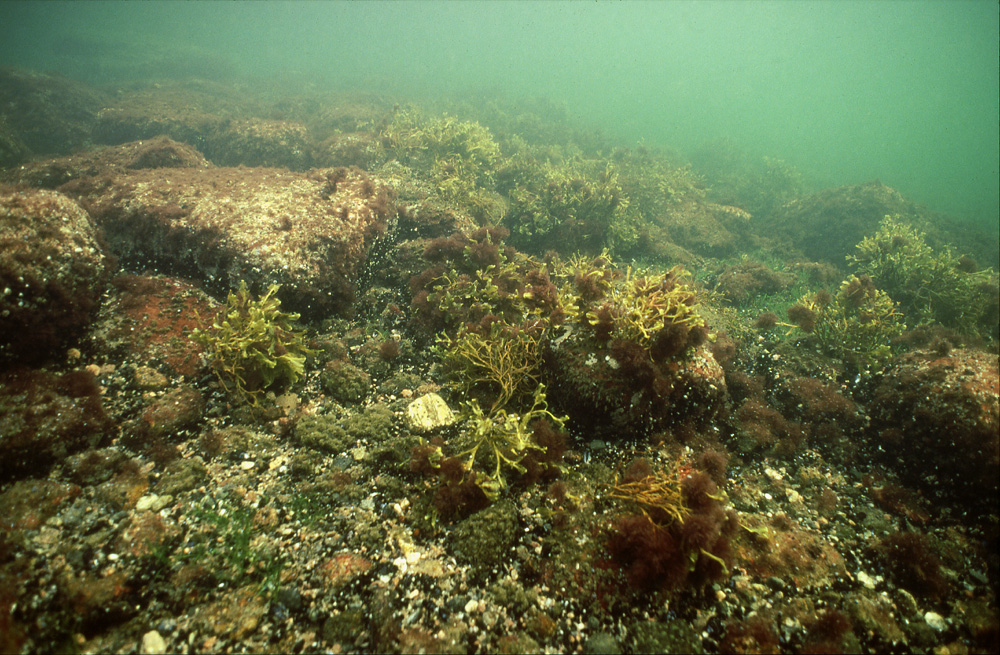

The bladder wrack, Fucus vesiculosus, dominates boulder and rocky shores of the northern Baltic to an unforeseeable extent. Why should just one species have taken over its niche when there are similar algae with similar properties at the same places where the F. vesiculosus comes from. Perhaps it should, rather, be asked what properties the other algae are missing that F. vesiculosus has, but the answer to that question is still unknown.

The bladder wrack comes from tidal coasts of the northern Atlantic and is accustomed to periodic changes of water level, even limited periods in the dry and the low salinity of rainwater. In the Baltic it has attained a number of adaptations, the ability to live in steady low salinity being the most obvious one. Its ability to float has increased but in winter it loses some of its buoyancy to keep the thallus down and prevent the ice cover from ripping it apart. On the other hand, without the tides, tolerance to drying out is not as critical and so the Baltic wrack has lost its tolerance somewhat.

Its remarkable ability to reproduce, though, has stayed the same. With the tides missing the wrack in the Baltic does not need to time its reproduction to the least amount of water flow during the tidal cycle. Nevertheless, timing is important since male and female reproductive organs are in different plants and fertilization takes place in the surrounding water. From the point of reproductive success it is absolutely essential that the male and female gametes are released simultaneously. So the Baltic wrac k still times its reproduction according to phases of the Moon but it also has additional regulatory features to prevent the release of gametes, should the conditions not be in favor of fertilization.

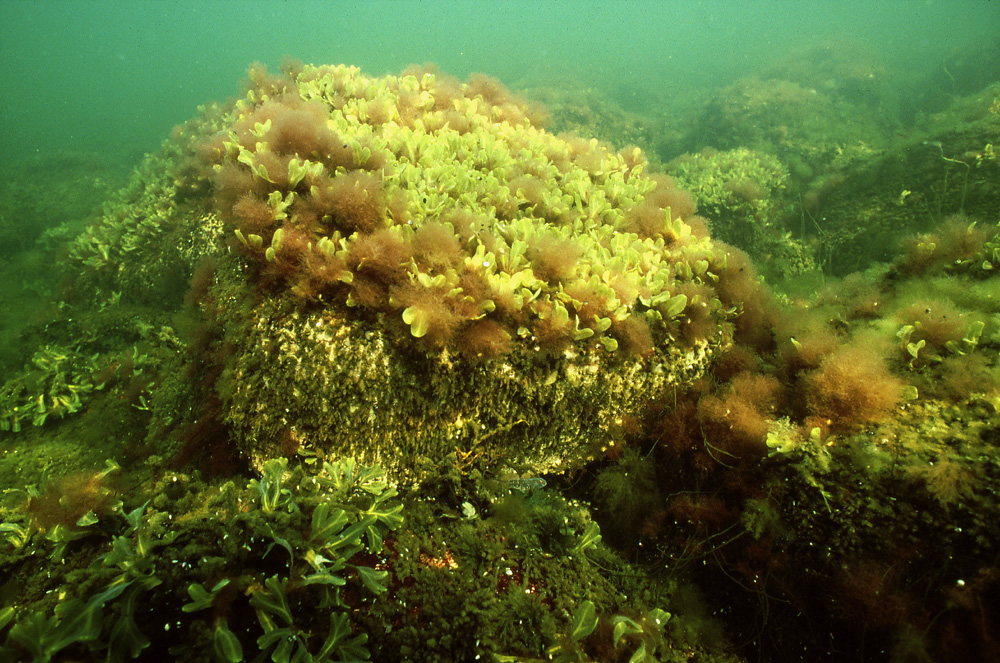

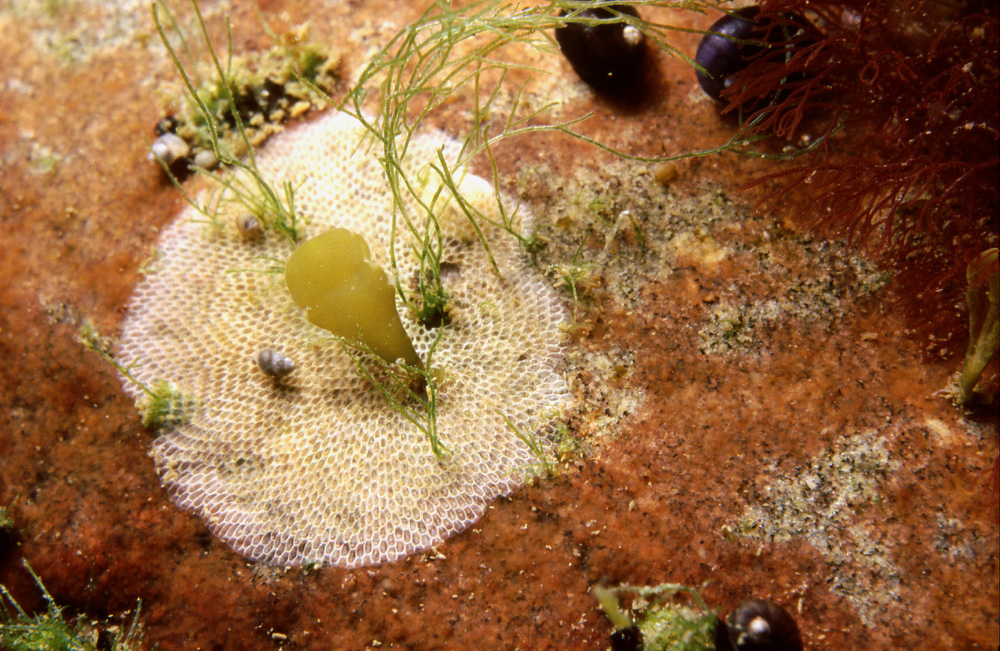

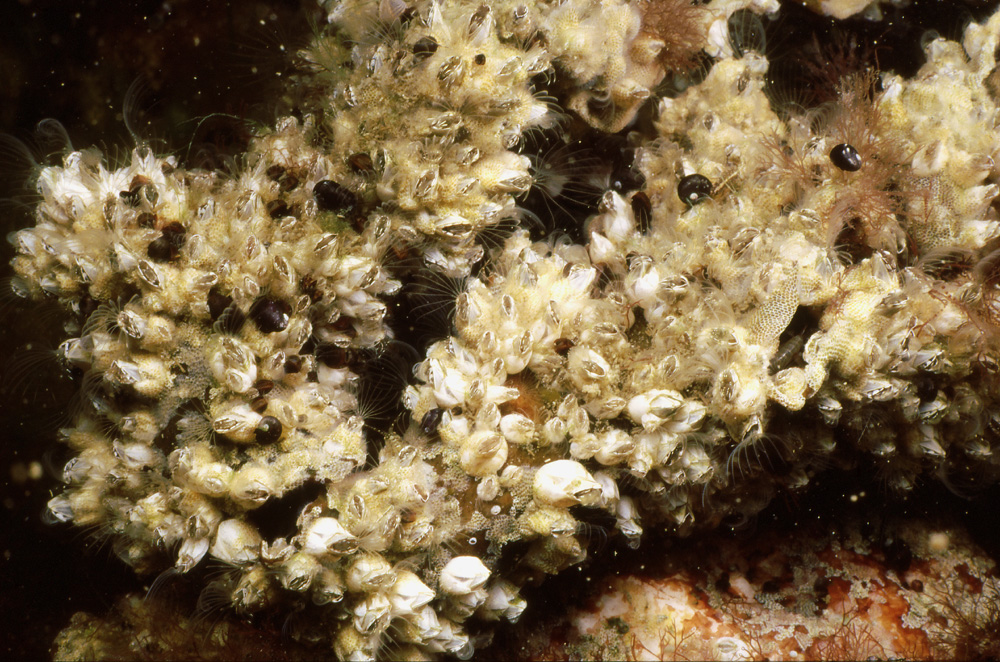

Although its reproductive success is remarkable, one needs to look for an explanation for this kind of accumulation of offspring. One of the possible ones is that ice has turned these stones over recently offering an area to settle on without much competition.

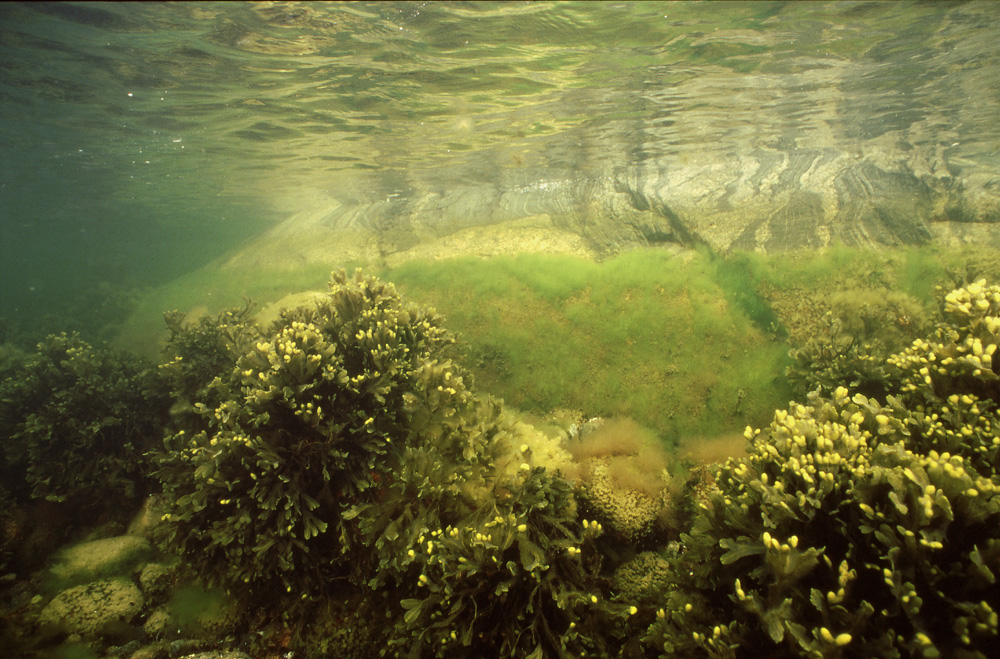

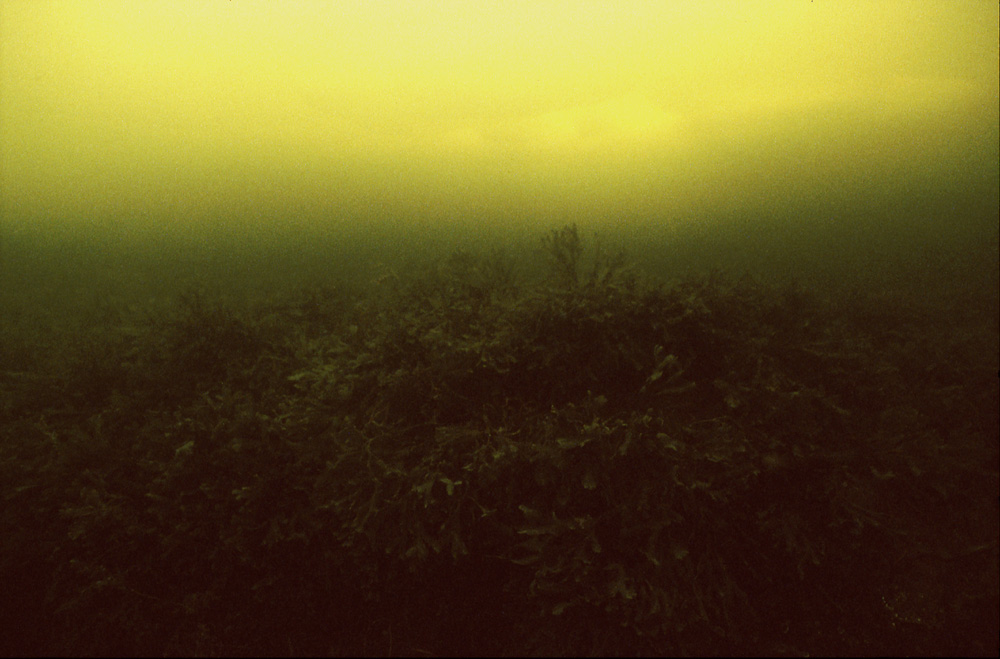

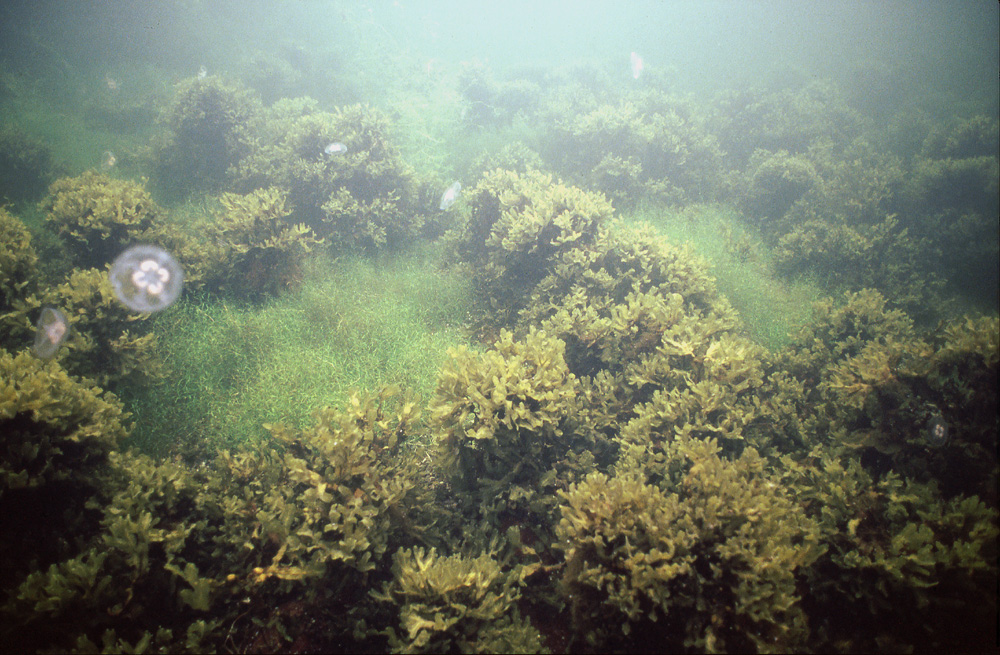

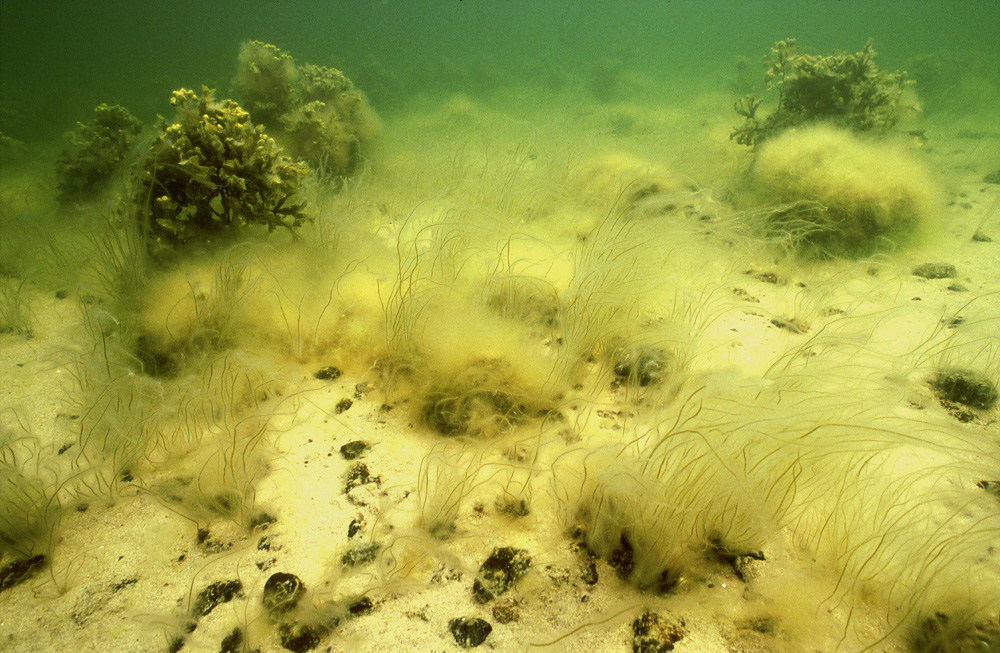

It may look that the wrack is competing for space to grow on in this photo but, in fact, the vascular plants, genus Zannichellia, are growing on loose bottom, spreading their roots into it, and the wracks are fastened to boulders by means of their holdfast.

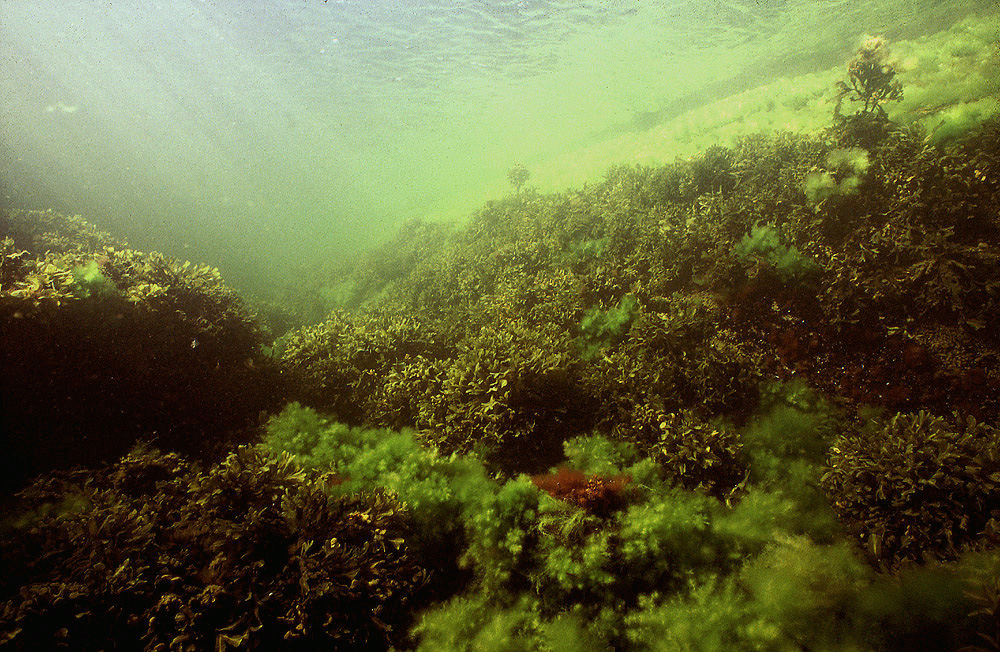

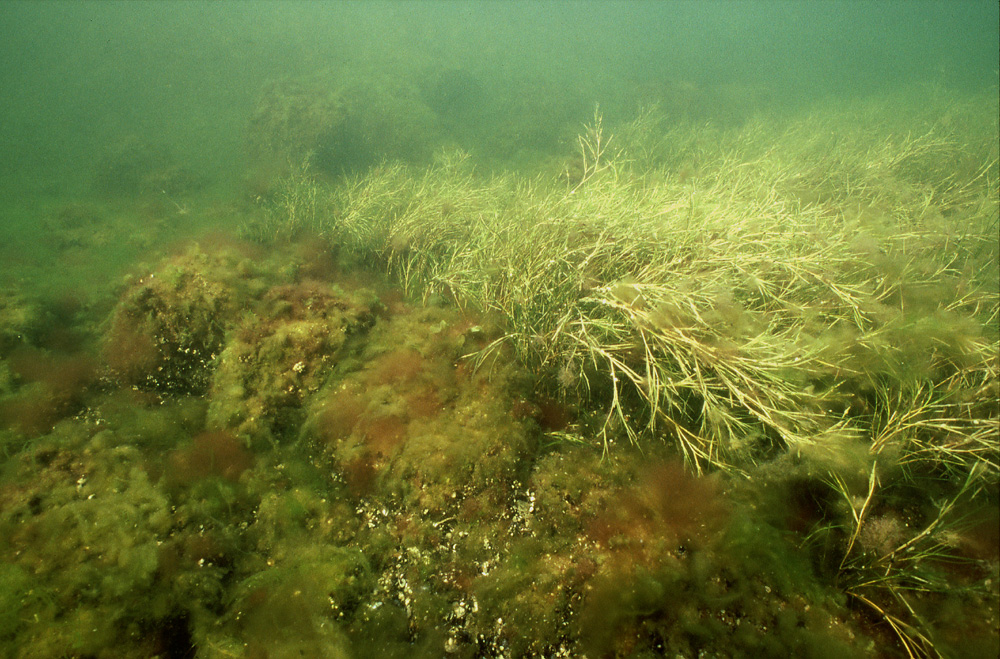

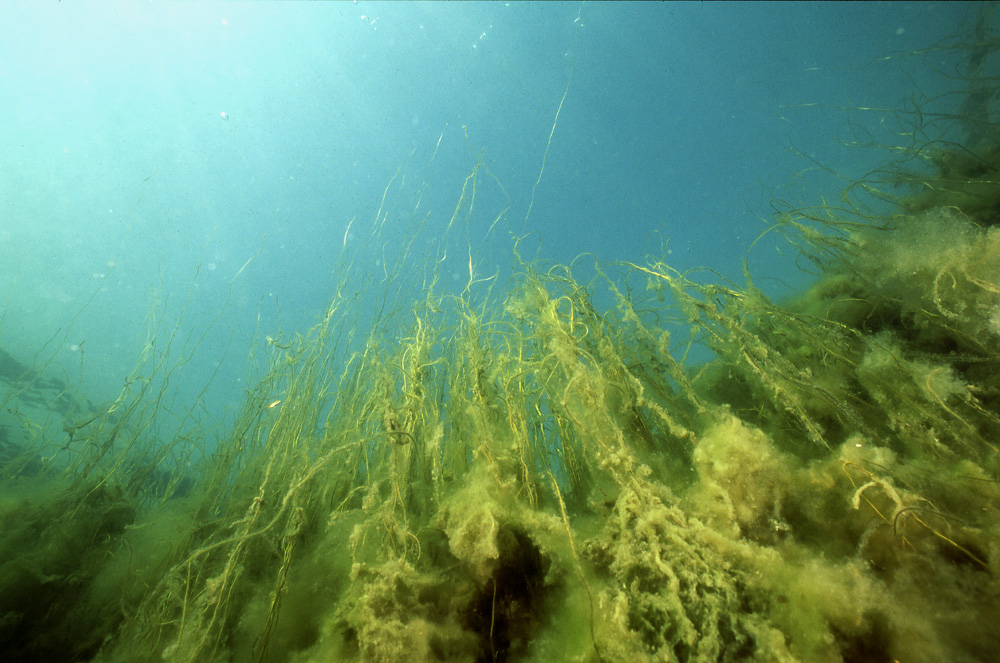

A similar situation with the previous photo but in this case the wracks are missing almost totally due to secondary stress from eutrofication and only the fennel pondweeds remain.

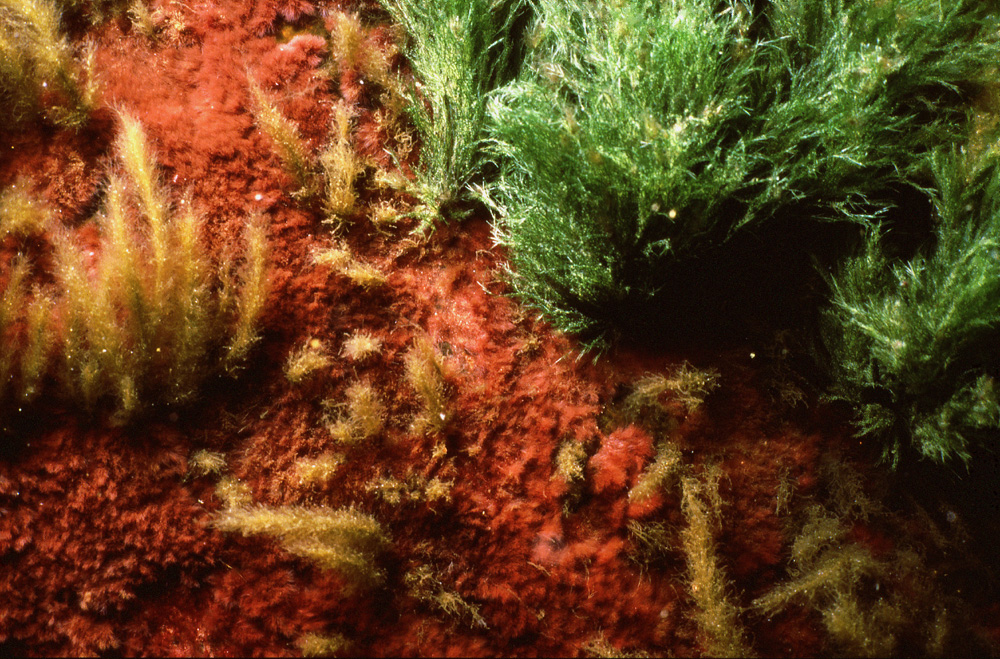

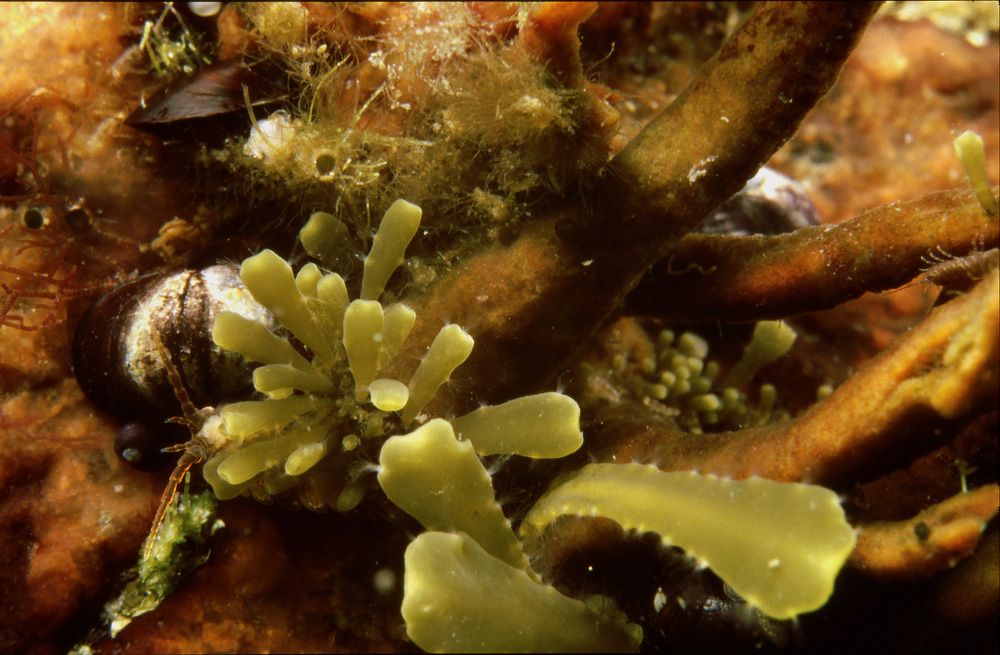

The threadlike brown algae, bootlace weeds, have always been present but in recent times they, too, seem to have had better growing opportunity due to the wrack declining. In the first photo they occupy stones that would be too small for a fully grown wrack. In the second photo they've invaded the upper edge of a rock wall. The spot could be too tight for any significant growth of the wrack but signs of improved conditions for bootlace weeds are there, anyway.

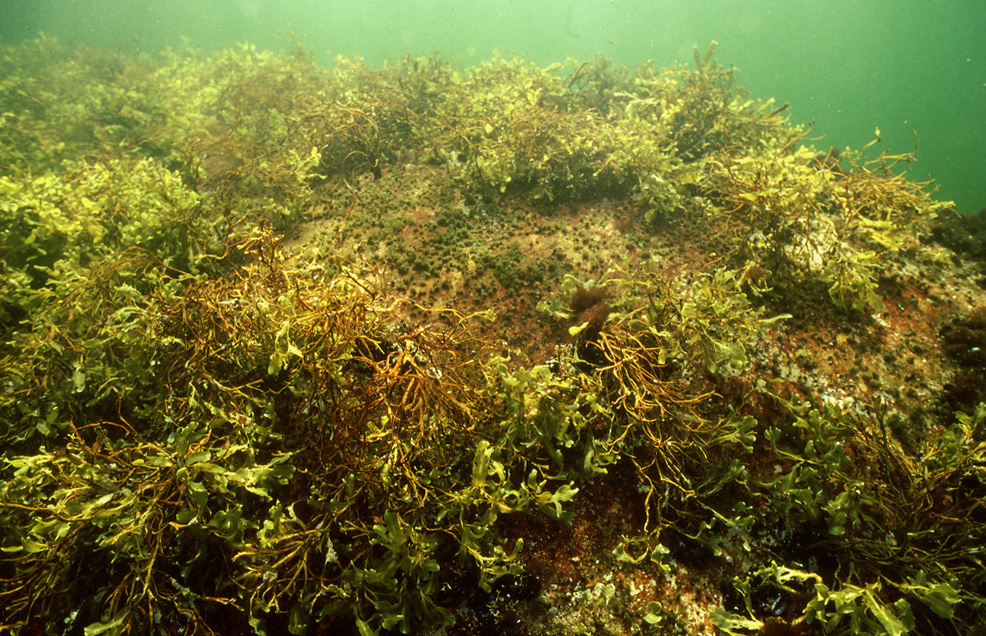

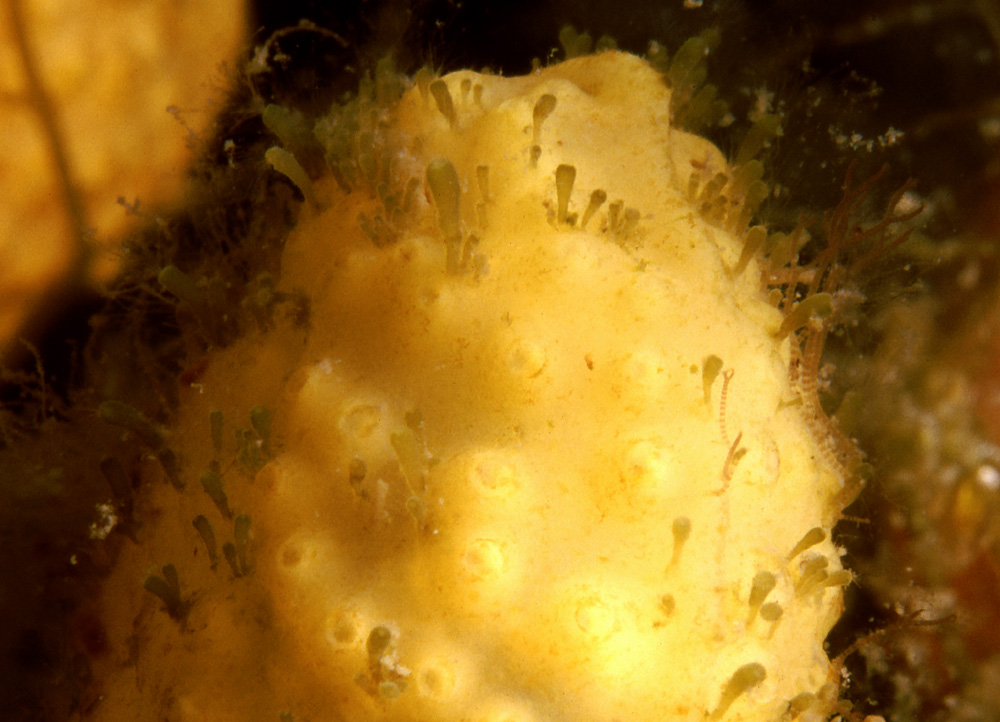

The sessile animals are just as much a part of the diversity of life on the bladder wrack. Too much is too much, though, and when the sessiles cover the thalli like this, they can suffocate and drag the algae down. This is just one of the ways in which the eutrofication threatens the wrack: without light and nutrition the algae starve and, eventually, die.

The early 21st century tendency was still towards diminishing growth of the bladder wrack, at least on moderately exposed shores. Even though some signs of improvement had been seen in more protected waters, most of the shores where these photographs were taken were in decline. In some of the locations algae being decimated by isopod grazing was the final sign before total absence.

|

Lisää pääkuvan päälle tekstiä klikkaamalla ratas-ikonia,

joka ilmestyy tuodessasi hiiren tämän tekstin päälle.