1. FROM THE FURY OF THE ELEMENTS INTO THE QUIET OF THE ALGAL BELT

Variations in water level come at irregular intervals in the Baltic. Unlike in the oceans, governed by diurnal variations, the plants and animals living closest to shoreline have no way of adjusting to the dry periods that can last from days to several weeks. In the Baltic the border between water and dry land simply wanders from one place to another according to the whims of the sea.

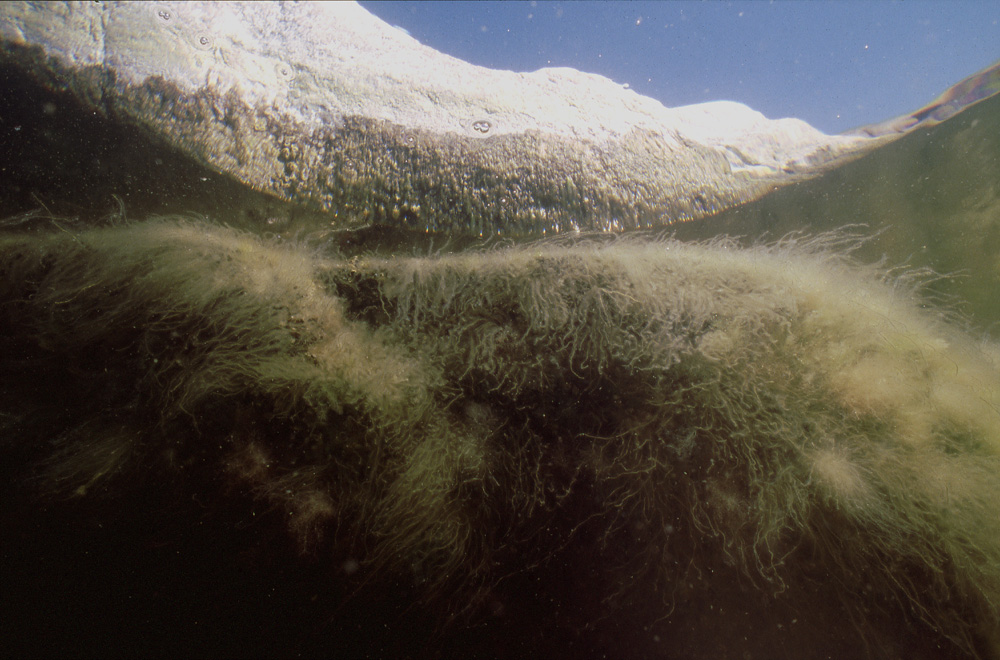

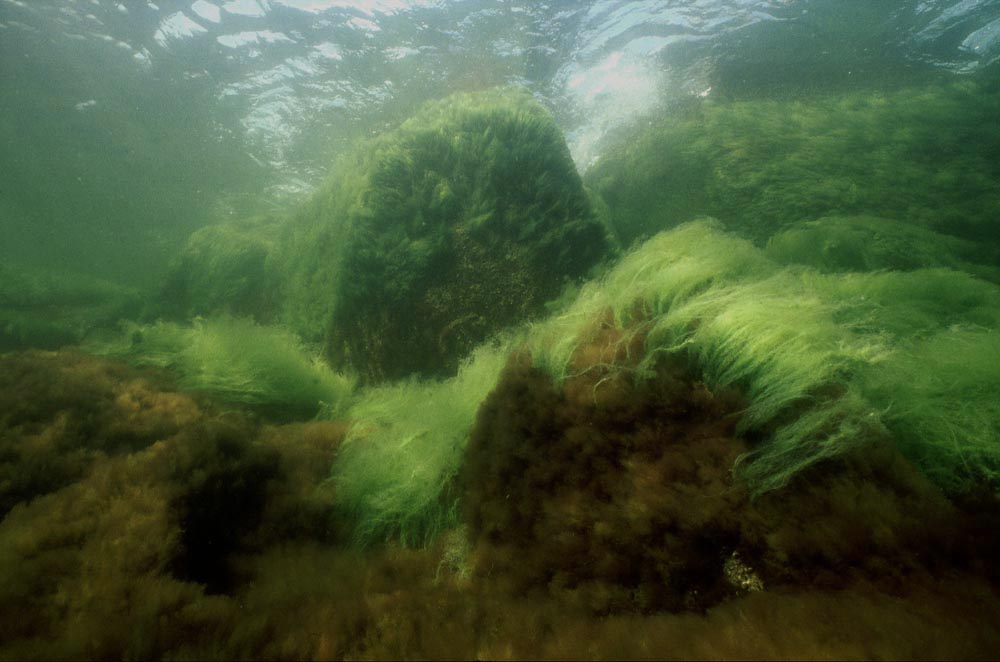

The shores do follow their own patterns of zonation in the Baltic, too, but the governing factors are different. Even if the water level is stable enough for a longer period of growth, larger algae do not survive the grinding of the ice cover occurring regularly in the zone closest to the shoreline. It's the filamentous algae, then, that prevail.

Besides showing differing reproduction strategies suited for surviving the winter various species of filamentous algae also each have their typical period of most active growth. Without oversimplifying it too much it can be stated that the summer period starts with the brown algae dominating, followed in succession by the green and, finally, the red algae.

It’s obvious from the size and structure of the filamentous algae that they provide an ideal living environment for only the smallest of animals. The instability and periodic nature of this habitat and its ability to catch organic matter means that it is as if made for the juveniles of a number of different species. They are the ones to make the most of life in this zone.

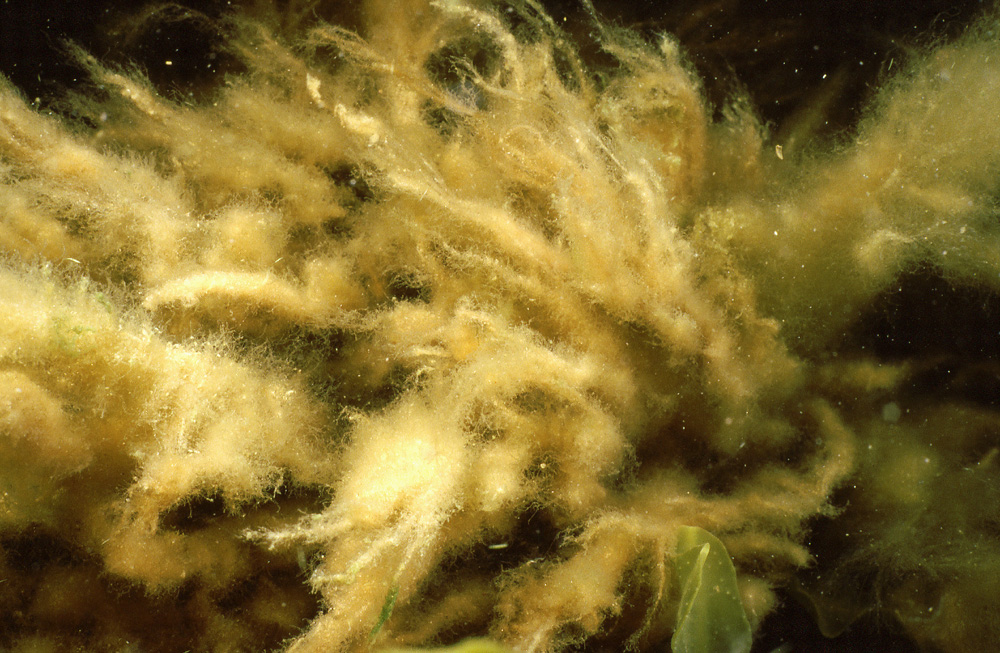

In spring the filamentous algae belt is dominated by brown algae, in these two photos by the genera Stichtyosiphon and Pilayella.

The recent eutrofication of the Baltic and, possibly, mild winters have had an effect on the abundance and distribution of algal species dominating the belt. Even the outermost islands of the archipelago show overgrowth of algae along their more protected sides, of genus Eudesme among others.

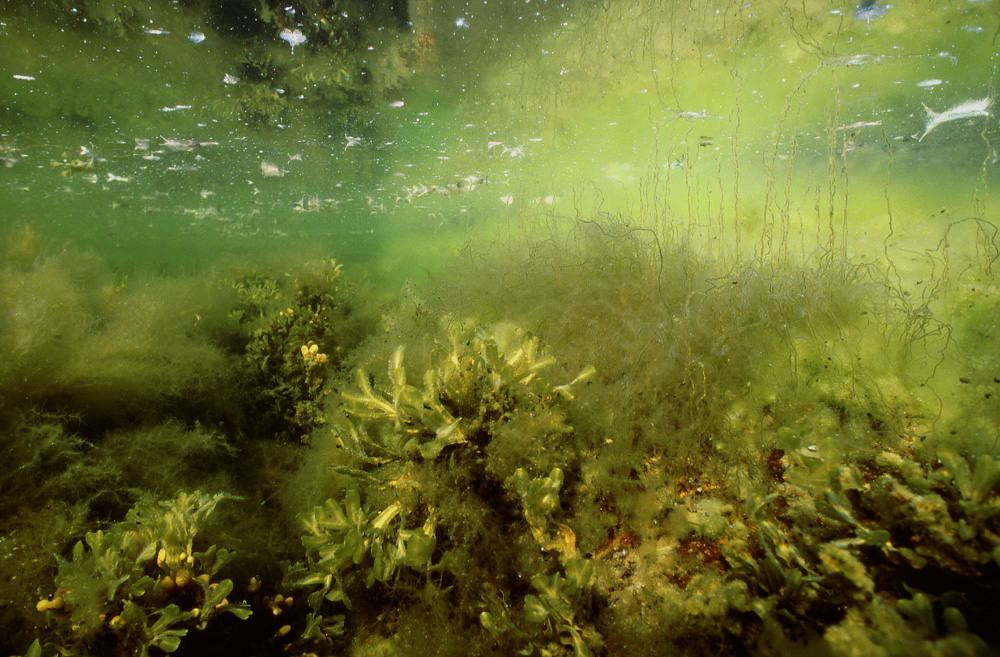

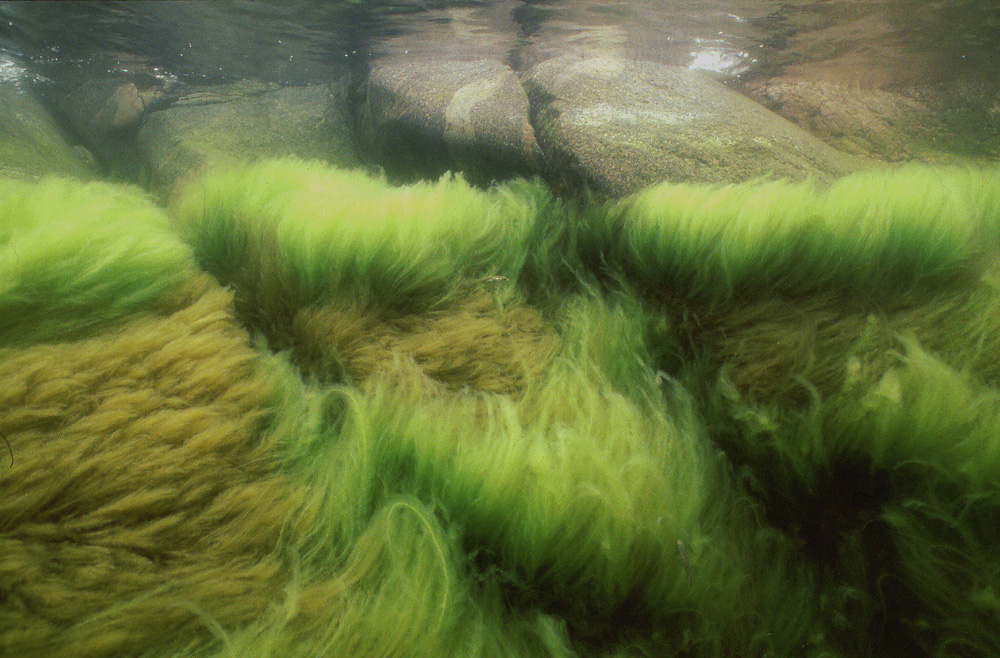

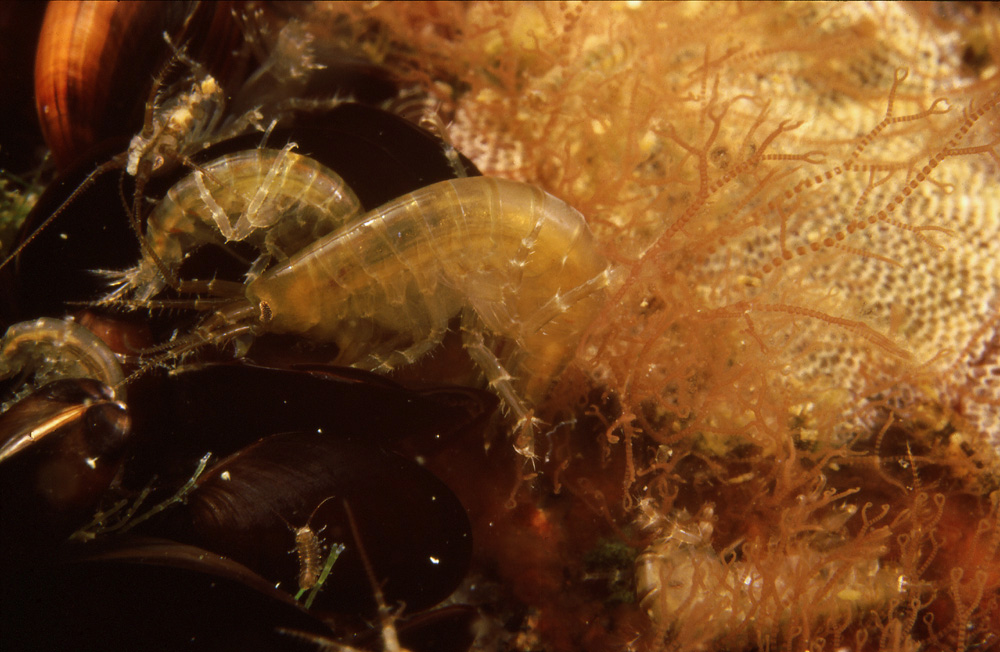

The prominent green algae of the zone are of genus Cladophora. The adult gammariid amphipods feed on organic matter on the algae rather than the algae themselves, unlike e.g. the juveniles of isopods of genus Idotea.

The recent history of water level variations can be read on the algal belts near the shoreline. In this case it is exceptionally clear from the green stripes of cladophoras that there has been a fairly long period of steady water level and that water has risen significantly in the days just before the photo was taken.

With the larger algae (mainly genus Fucus) having diminished recently the different color forms of the filamentous algae dominate even larger areas near the shoreline than before. In this photo Cladophora still dominates in August but red algae are slowly taking over.

Genus Enteromorpha, too, seems to have increased in abundance recently and can even dominate, typically right at the shoreline, later in summer. It can provide an environment suitable for various small animals but is also grazed upon by large birds like swans.

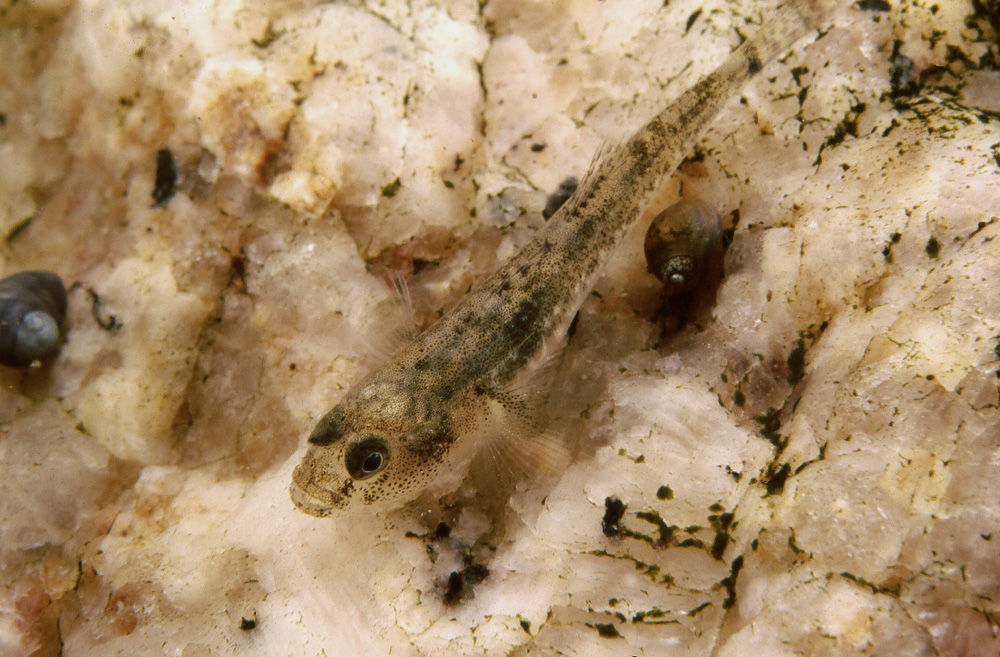

One of the fish species most typically being seen close to the shoreline is the common goby. It can frequent even areas having just been submerged after a dry period, indicated here by the nonexistent algal growth on the rock.

Flatworms usually live under stones or among larger algae. Hiding away in this manner they can, nevertheless, be easily spotted by turning over a stone.

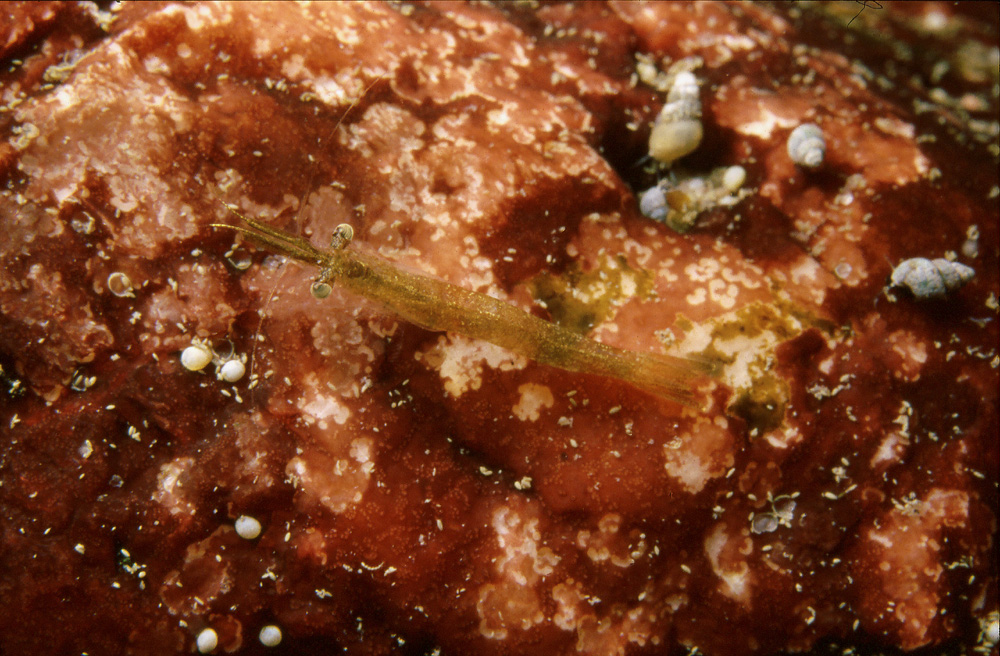

The upper algal belt is sometimes formed by just a thin layer of algae, e.g. by genus Hildenbrandia, as in this case. This film of algae is showing signs of grazing, most probably by gastropods of genus Theodoxus, not by either the mysid shrimp or gastropods Hydrobia appearing on the photo.

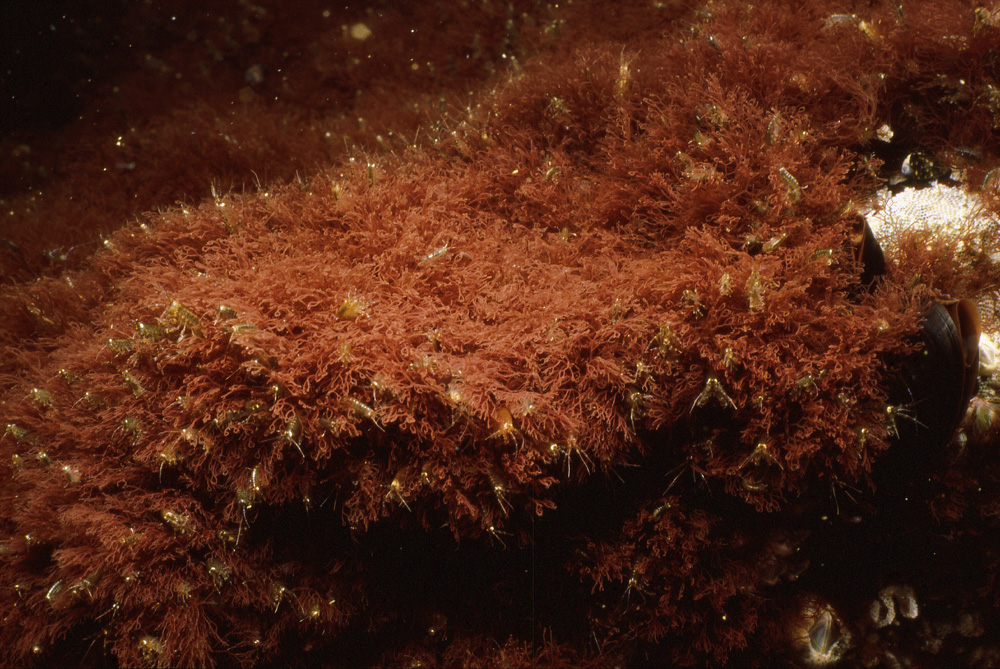

When the green algae are gone, the filamentous algae belt is dominated by the red ones, most typically of genus Ceramium. The algae combined with loose organic matter form a carpet-like layer on rocks and stones, making it an ideal surroundings for a number of small animal species. What could be more suited for living in these carpets than worms? Of the medium-sized worms nemertineans abound but even larger ones like Nereis (first photo), more commonly living in sand bottoms, can be found.

Annually, the gammariid juveniles are actually late-comers in comparison with the idoteids, and towards autumn they can sometimes be found in great numbers in the red carpet.

Autumn is a period of storms and with the current weaker growth of larger algae the shores can look very barren indeed just before the onset of winter.

Winter always comes but rarely, nowadays, does it form a continuous ice cover all the way to the southern Baltic proper. In fact an ice cover like this one, making it possible to drive by car to even some of the remotest islands of the Archipelago Sea is now rare

|