4. IN THE REALM OF THE SESSILES

It may be daring to speak of the cliff habitats as the counterpart of the coral reefs or even rocky shores of the oceans. And it’s true that while reefs are formed by the calciferous structures of living organisms, rock walls are just that: rock, born out of the seismic processes of the earth’s crust and refined relatively recently by the ice age.

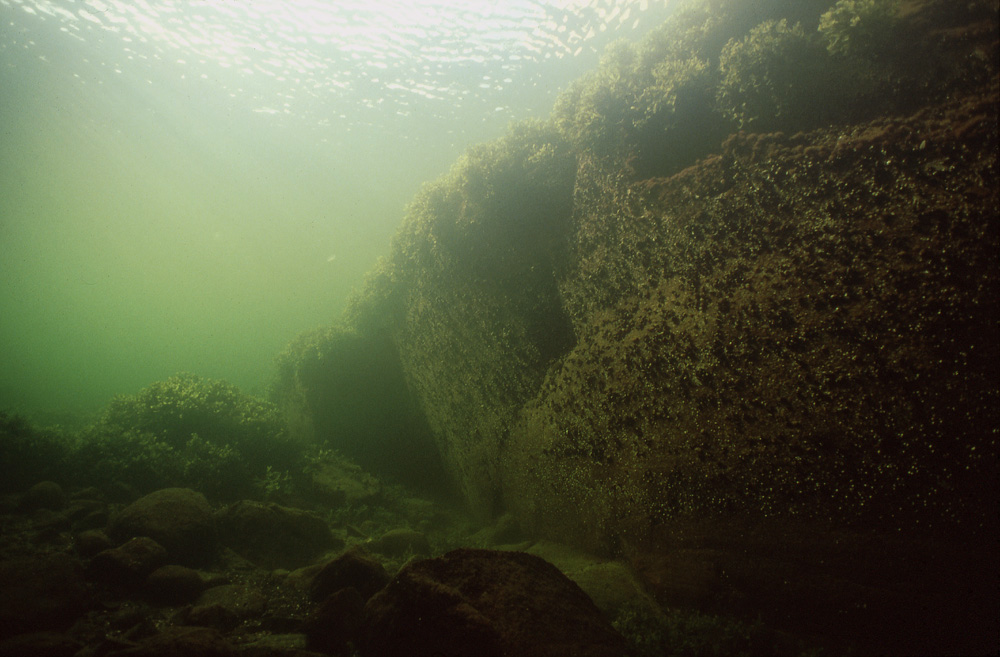

But the similarities are there, too: the relative diversity of the cliff is the result of the activity of mainly the sessile animals taking their nutrition directly from the water surrounding them. The major difference is that on the cliffs of the Baltic there are only very few species of sessile animals, the blue mussel being the overwhelmingly dominant one of them.

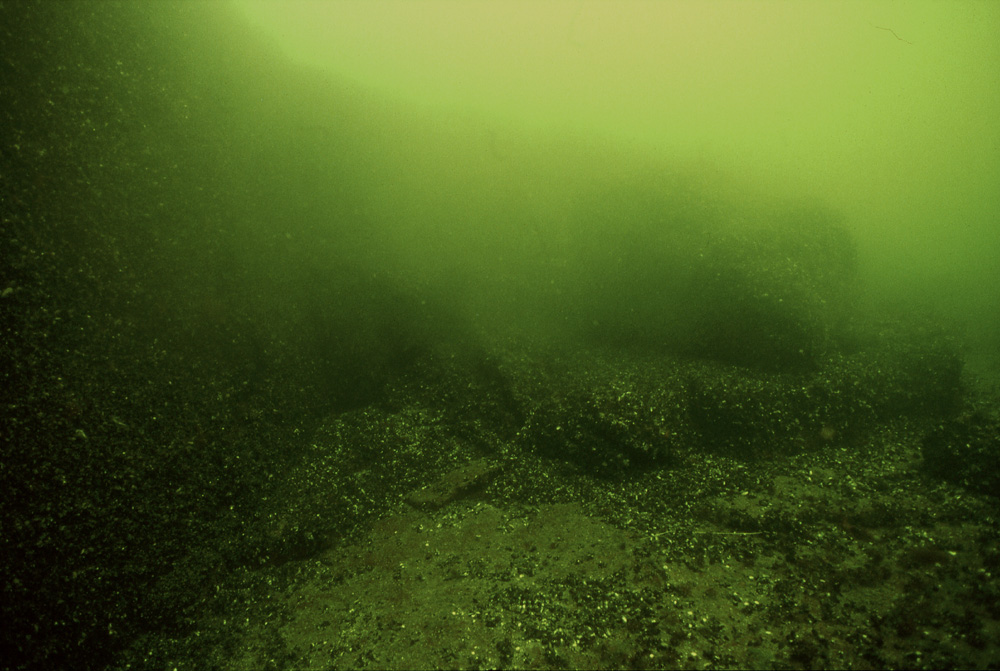

Although the ecosystem of the Baltic cliffs is fairly simple, little is known of the zonation or variations of dominance of the animals. It’s easy to observe that certain species tend to be more abundant on locations best suited for their form of life but even the ongoing decline of the blue mussel at the turn of the century is lacking an explanation.

From the point of view of photography the cliff is quite rewarding: although often minuscule in size, the animals and plants cannot easily hide away from the human observer. They tend to stay put relying on their camouflage and show a pretty variety of color, too.

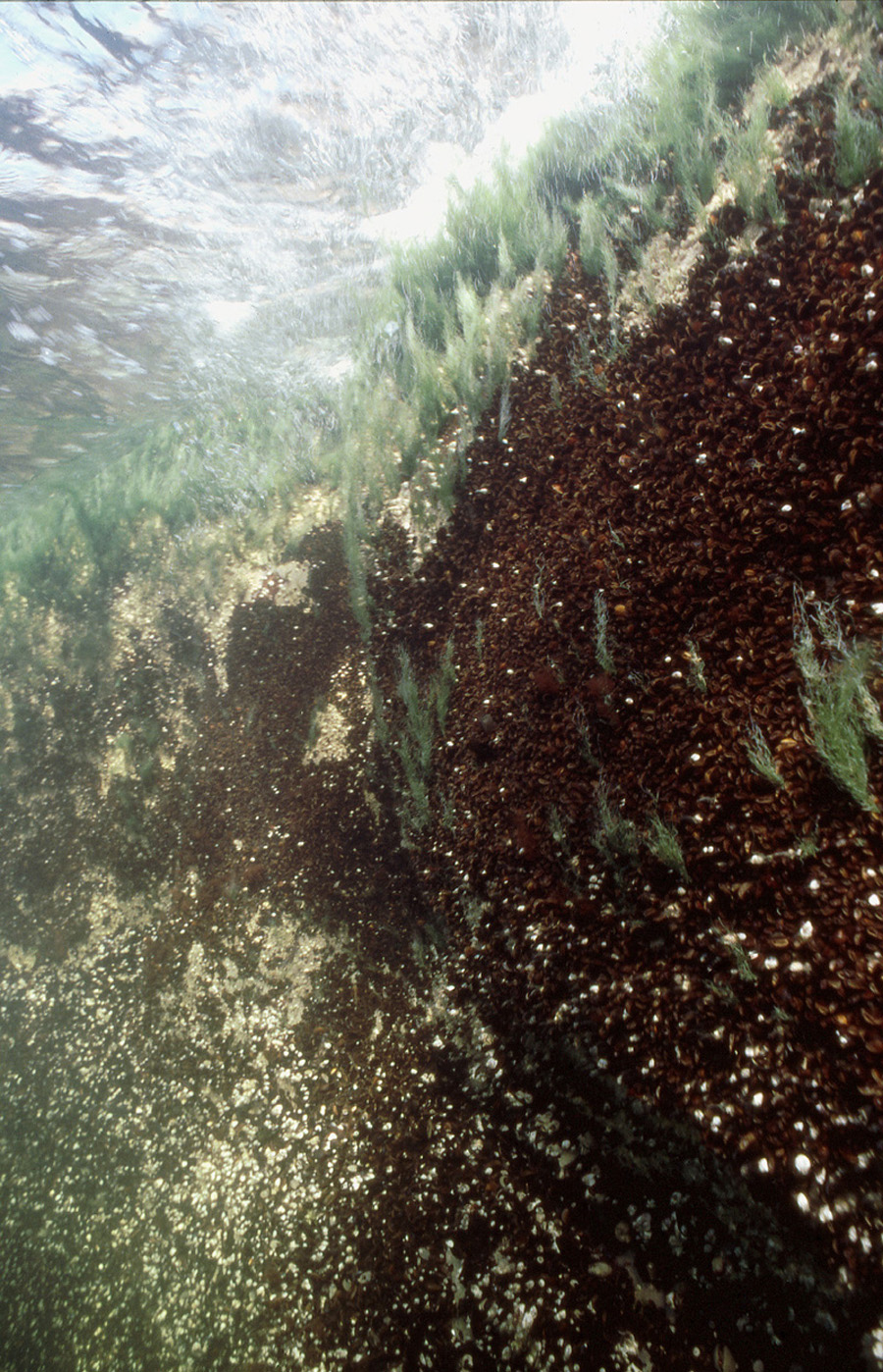

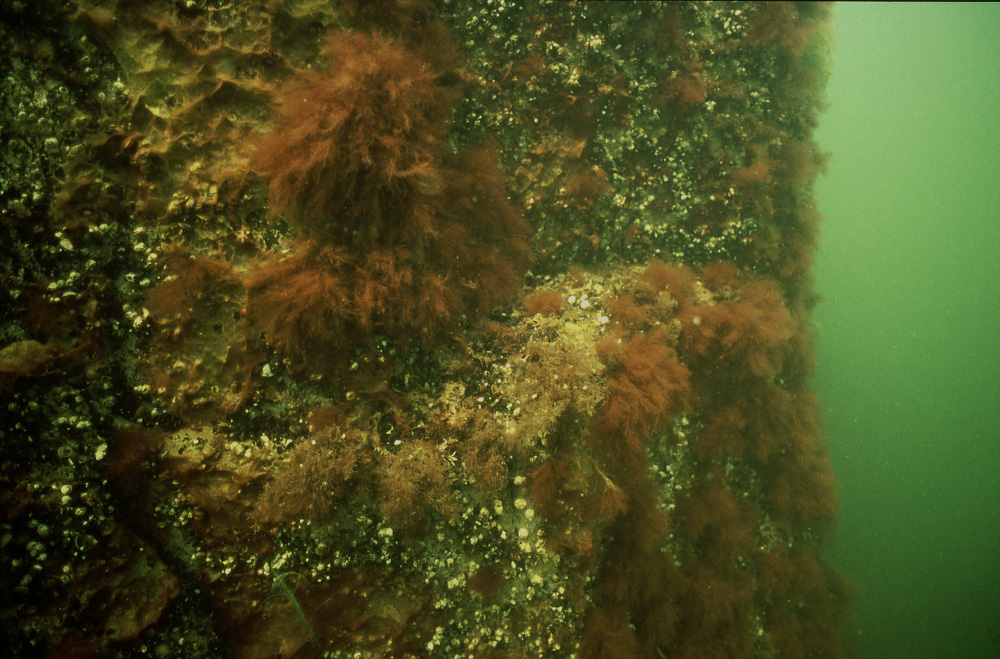

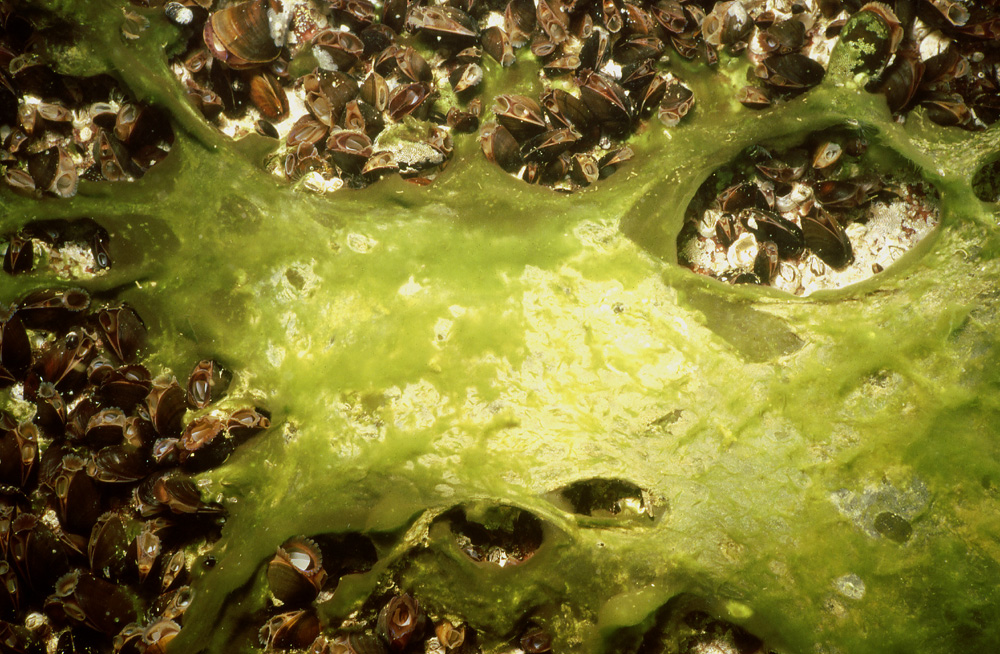

The cliffs come in different shapes: here the wall starts from above the shoreline, giving the larger algae little room to grow on. The abundance of the little blue mussels could be taken as a sign that there has not been a thick ice cover the winter before this photo was taken.

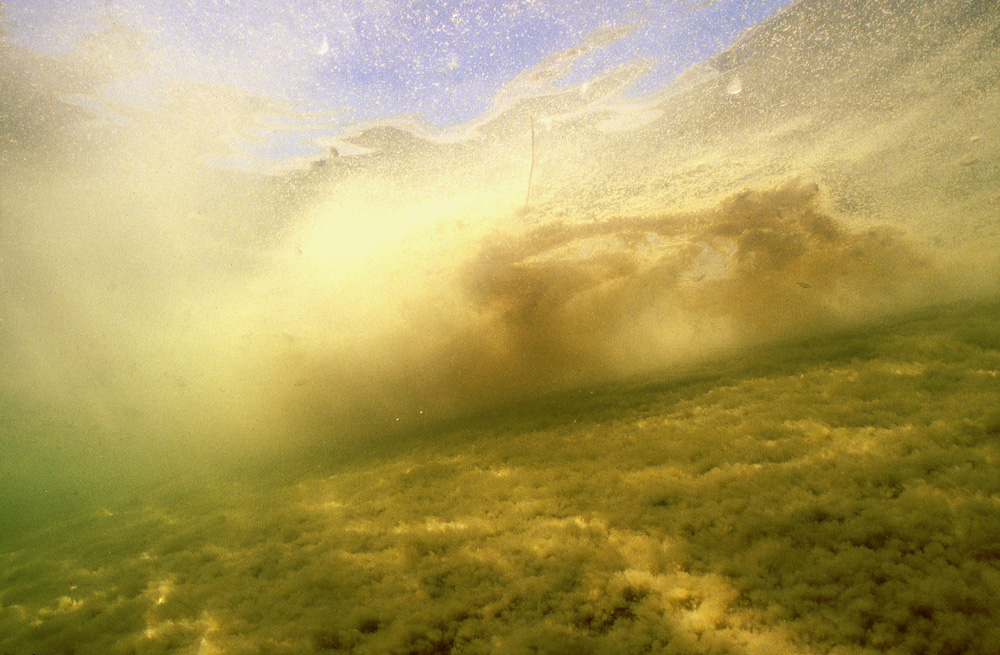

The first algal bloom of diatoms, in spring, is vital for the blue mussel growth in general and its reproduction effort in particular. Typical for the bloom is that it turns the water brown in color, the change usually starting even before the ice has melted totally. Later, before midsummer, the diatom bloom is followed by others, often even more distinctive. The second one here, pollen of the Scots pine, has little to do with the condition of the sea whereas the third, blue-green algae bloom is indicative of the recent eutrofication of the sea

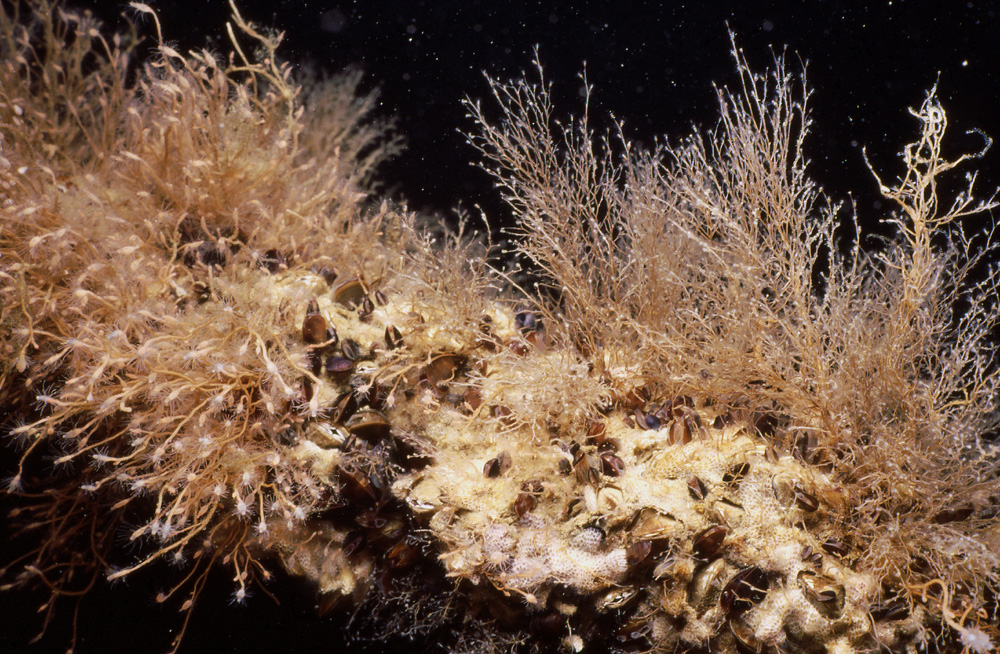

In this place there is a cliff top, where the wrack has enough room to grow under the ice cover of winter. The location is in the outer belt of the archipelago where the decline of the mussel is, allegedly, even more clear than in the middle parts.

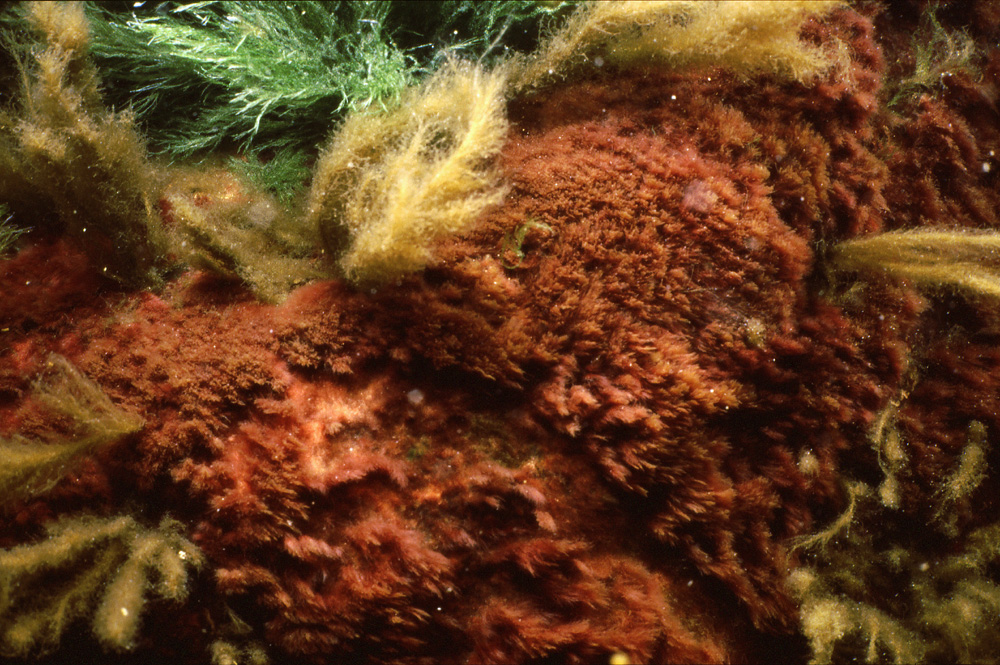

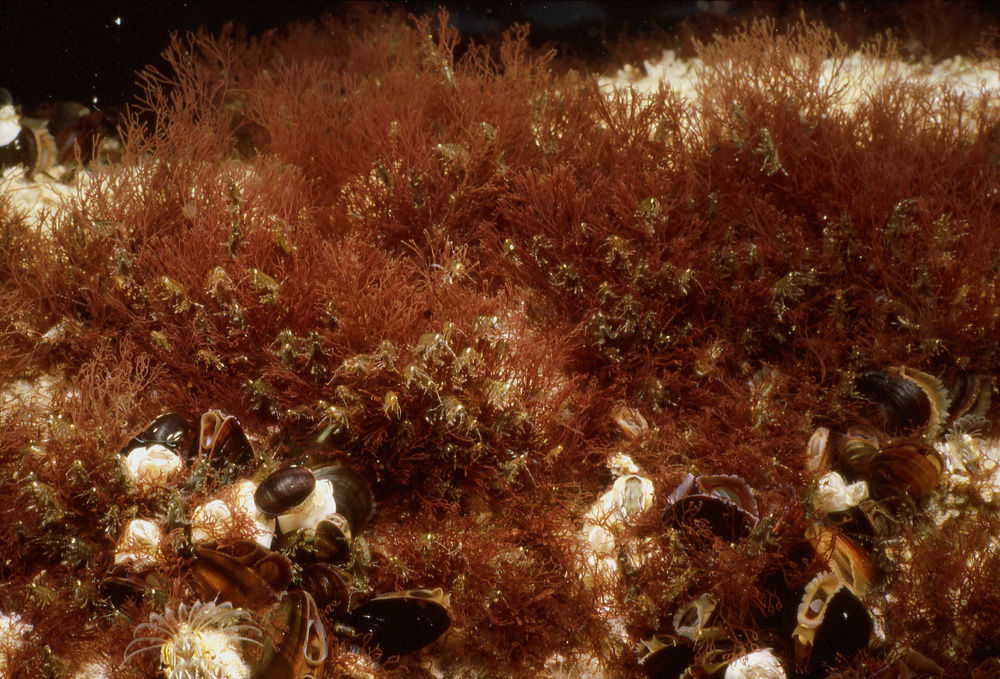

Underneath the wrack and in the upper parts of the cliff certain species of algae often grow, getting just the right amount of sunshine and being protected from excessive competition by the constant movement of wracks in the waves. Some of the typical species for these conditions are the carpet-like Audionella sp, the green Cladophora rupestris and the more broad-formed Phyllophora sp.

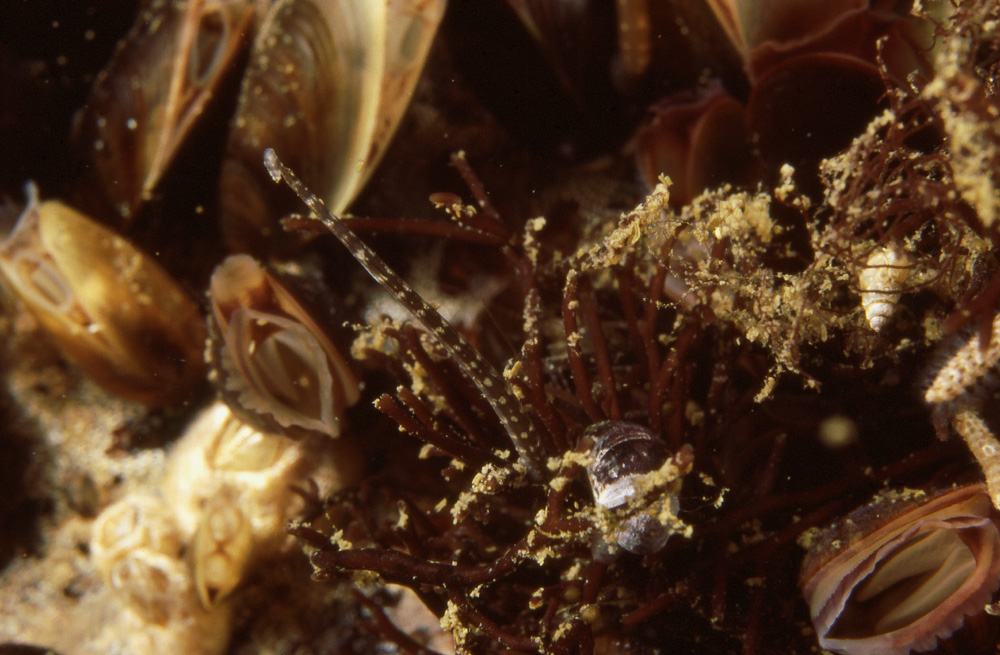

Going down along the cliff the red algae dominate, filamentous ones mostly in the upper parts and Phyllophoras in the lower.

Blue-green algae of genus Spirulina seem to be on the increase. Certainly, at places they are abundant enough to be suffocating to the sessile animals of the cliff.

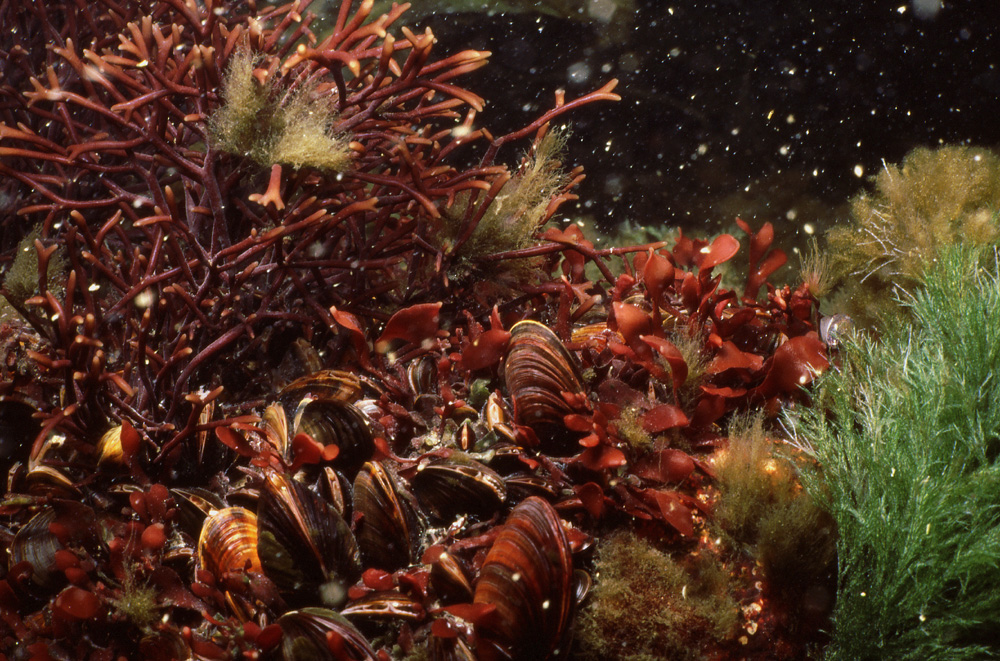

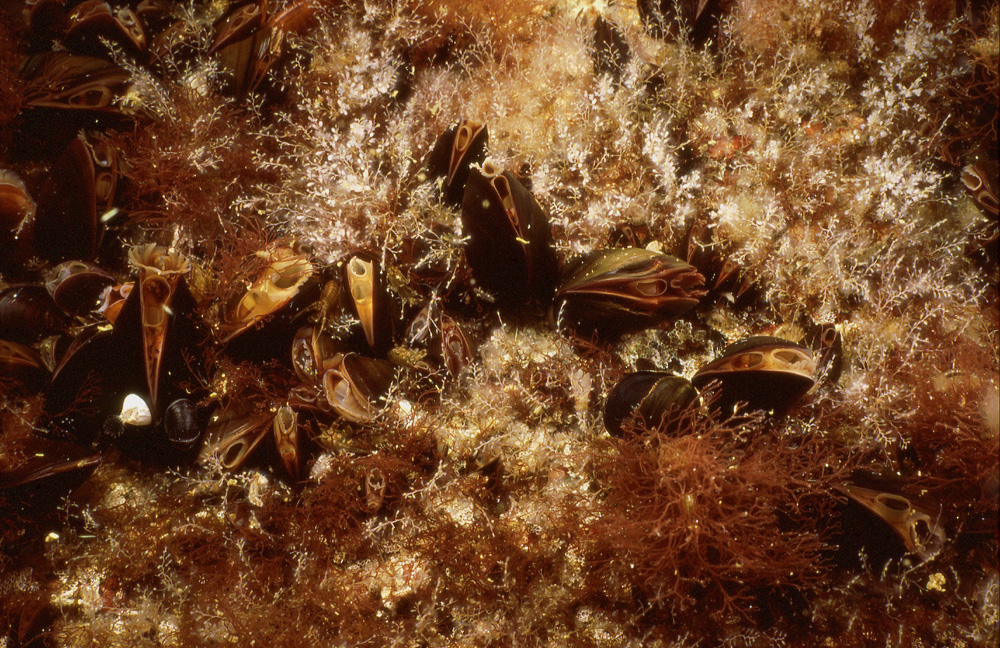

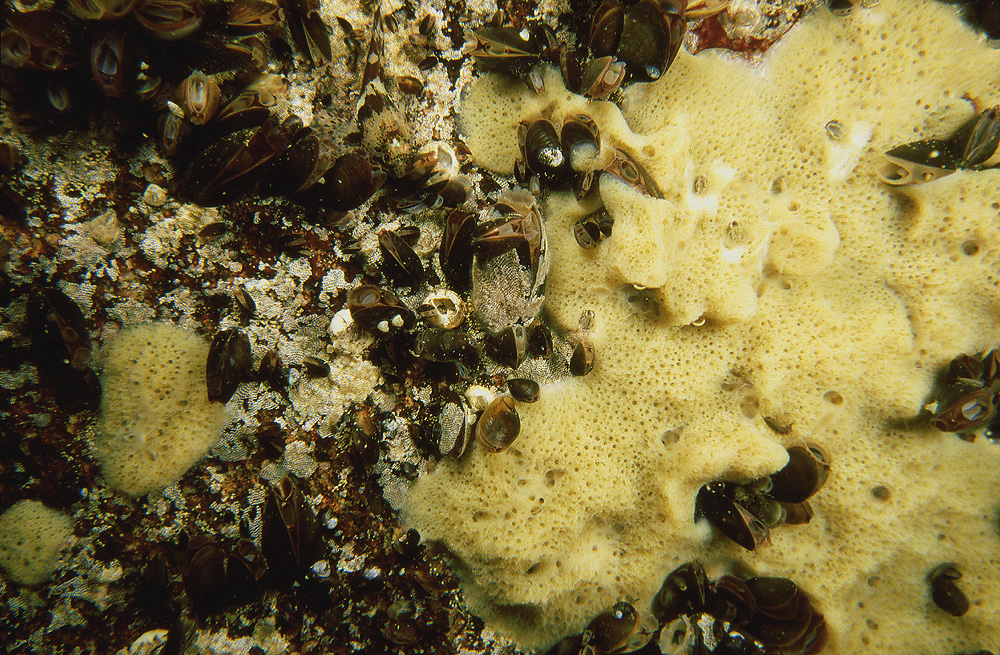

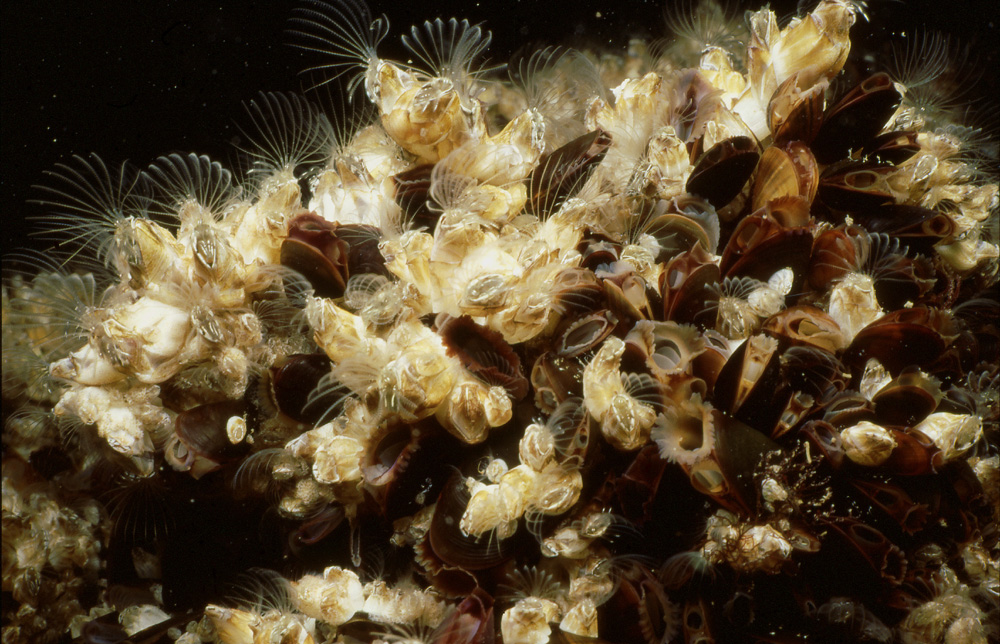

Blue mussels (recent studies suggest that they are of the species Mytilus trossulus) are still so abundant that they filter significant amounts of organic matter from the sea. It’s been calculated that together they are capable of filtering all of the water of the archipelago annually. The gills of the bivalves do the double job of breathing and filtering the food. Once the mussel settles on one place, it is anchored so strongly that it cannot move at will. If loosened by external forces, the foot will make it possible for it to move to another place and create threads to tie it down again.

The best places to grow, from the viewpoint of the mussel, are the ones where there is enough flow of water and protection from too much of the organic matter falling on them. At such locations the mussels can dominate close to hundred percent, at others there can be surprisingly high number of other species competing for a place to grow on.

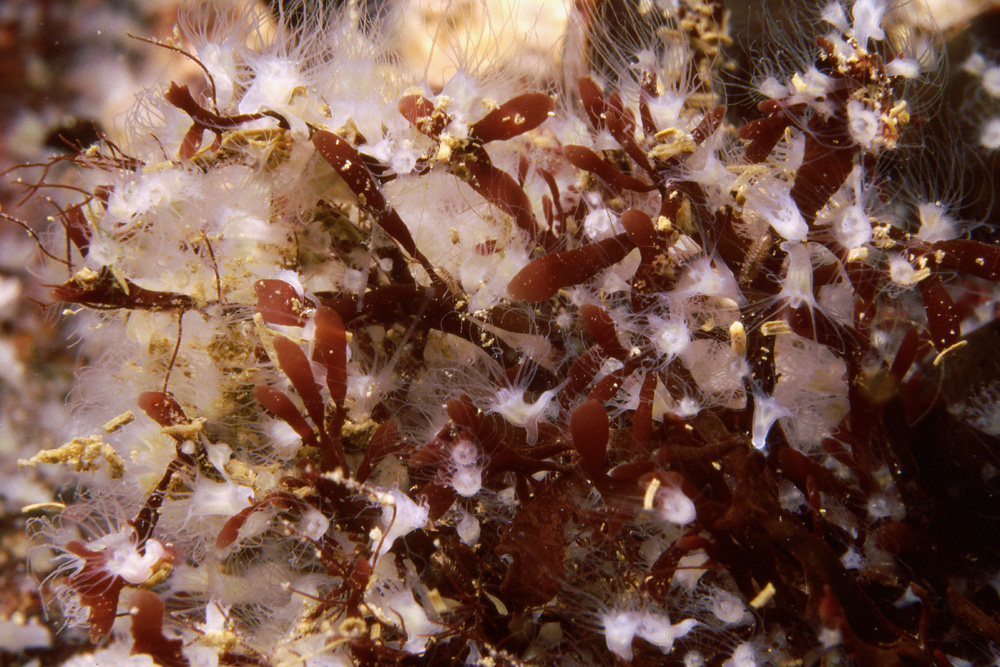

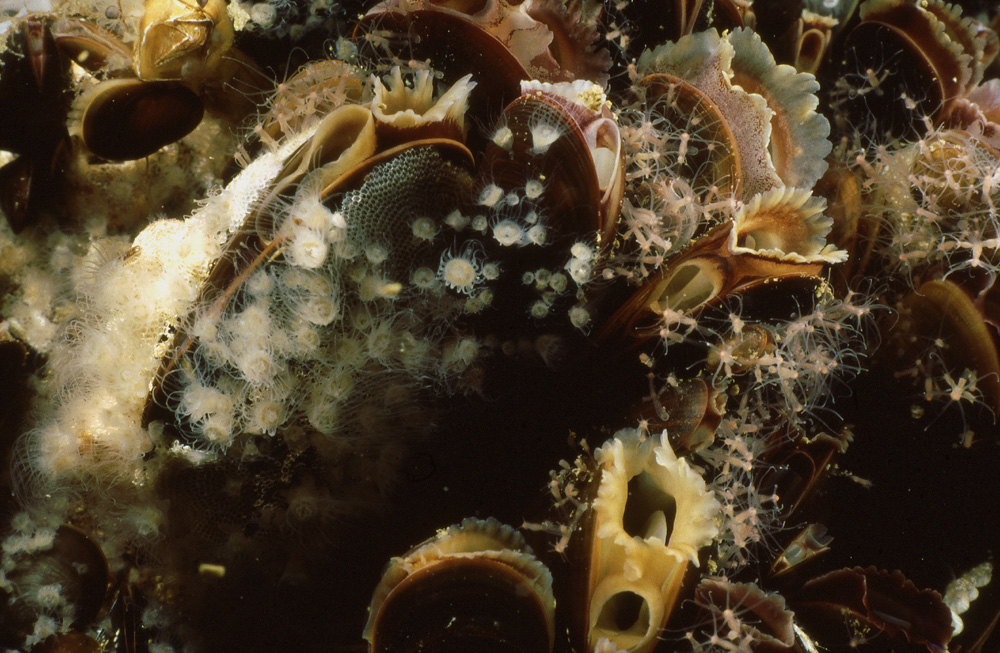

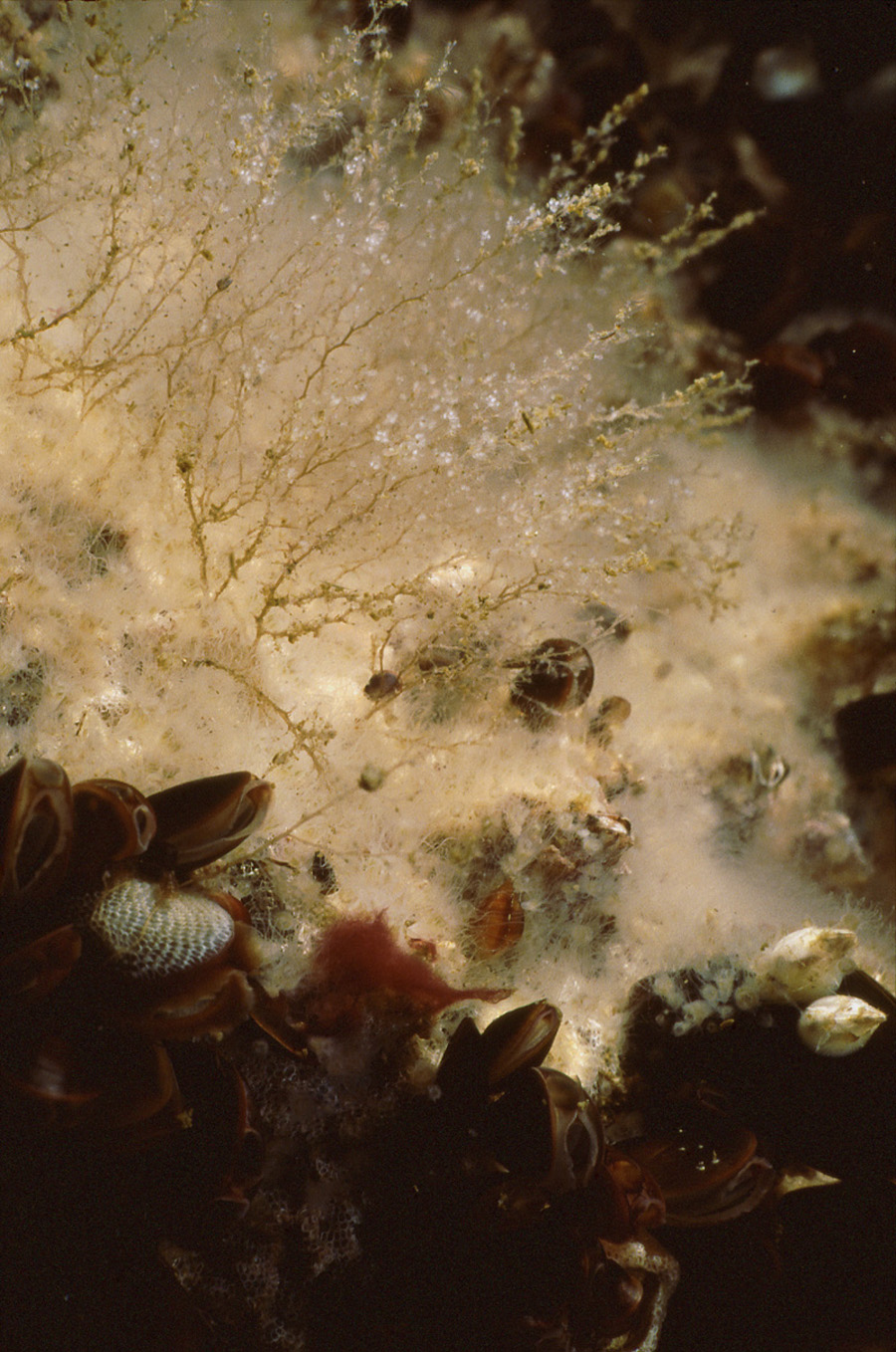

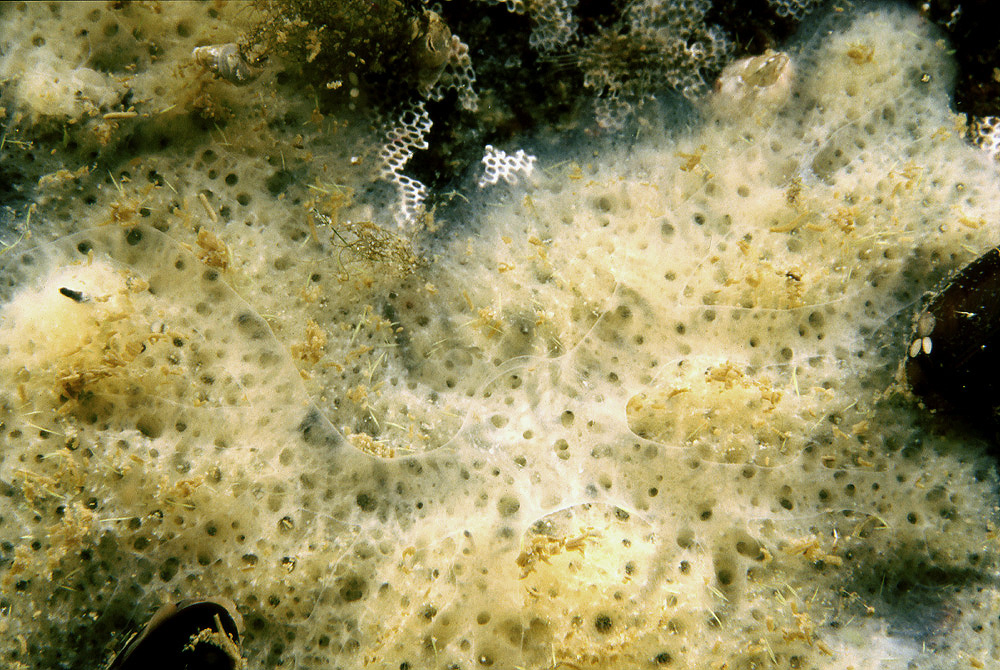

The upper parts of the cliffs are usually occupied by the smaller filamentous algae. Of the sessile animals the moss animals of genus Electra are often the dominant ones, and for a good reason: their reproduction period is earlier than that of most of the other sessiles and they are therefore the first to reoccupy the parts destroyed by the winter ice cover. In fact, with the decline of the mussel the appearance of other layers of the wall has started to change towards a general whiteness, for which the spreading of the electras is just one reason.

Two of the typical fishes of the cliff are the black goby and the scorpion fish. In the upper parts of the cliff the juveniles of these fishes have enough hiding places in spaces created by the sessile animals but in adult life they move downwards to seek shelter in the crevices (in the case of the goby) and hunt in a surrounding better suited for their bigger size.

Some of the most typical motile invertebrates of the cliff are the various species of gammariids. The juveniles may occupy the filamentous algae belt at the top of the cliff in great numbers in autumn but when the conditions are calm, even the adults sometimes congregate in unlikely piles at the shoreline

The colonial hydrozoan Laomedea lovenii is more abundant than Cordylophora caspia and can cover wide areas of a cliff, from the shoreline all the way to a few tens of meters down. Cordylophoras, although more outstanding, grow only here and there and the colonies are smaller in width.

Barnacles grow on any firm surface, as every boat owner can tell. One of the earliest immigrant species with a known record of arrival, it is doing well in the Baltic. Although the reproduction is only once a year in the Baltic, instead of the twice a year of the oceans, the barnacle will spread eagerly everywhere. Being a hermaphrodite it can always fertilize itself, if there are no other barnacles around to use its remarkable penis on.

Also typical of the cliffs but found only at places is the sponge Ephydatia. Although defining a single specimen is difficult here, the colony grows in coordination, as if it was a single specimen, forming channels for the flow of water.

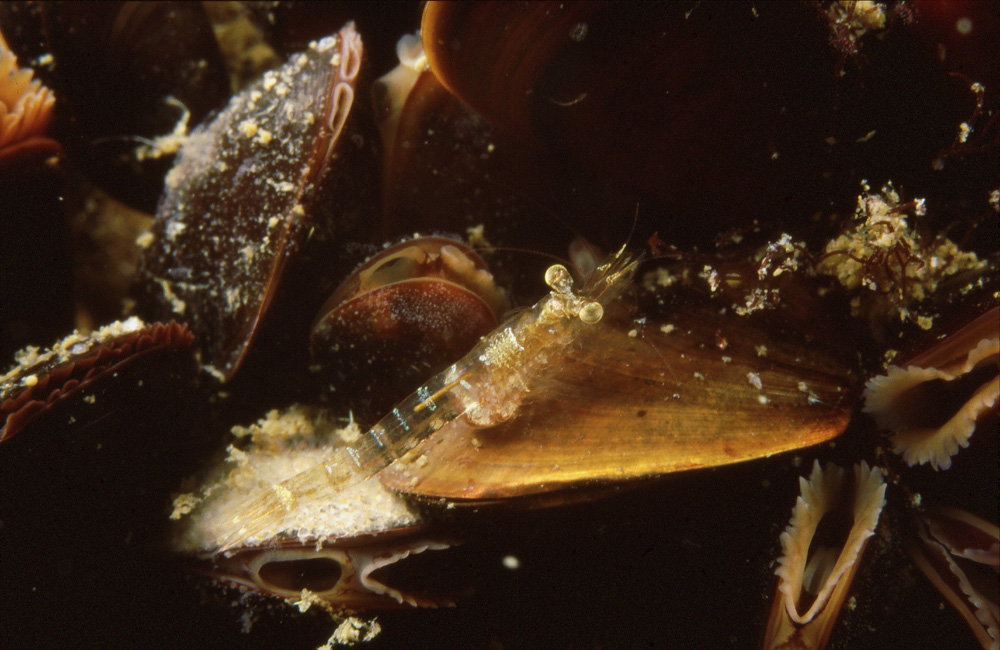

The cockle Cerastoderma glaucus normally lives its adult life buried in a soft bottom but during its youth it can be seen on algae or fastened whatever happens to be available. At times in great numbers, it should be added.

Should we not also mention the more elusive of the cliff animals, like the worms. Here there are two examples, the common ragworm and the fish leech.

In the smallest scale available for a well-equipped photographer the world of the cliff reveals itself as ever more fascinating. The sea slugs (the second hiding left of the more obvious one, behind a small bunch of organic matter), for the naked eye, appear as just a whitish spot. And the four small Jaera isopods are in fact abundant but usually not noticeable at all. The jellyfish polyps, the gammariid amphipod, barnacle, mussels and moss animals are the more usual inhabitants, which, at least in great numbers, catch the eye of the beholder.

All of the six northern Baltic mysid shrimp species (counting Mysis relicta as just one) can be seen at or near the cliff, at one time or another. The Neomysis integer, a number of which can be seen on this photo, is a regular inhabitant as are the two species of Praunus. With a bit of imagination both of the Praunus species can also be spotted. Praunus inermis, in the second photo, behaves here as it does in the wrack belt, drops down when threatened. That is all it does, though, luckily for the photographer, because it can then be photographed easily.

The moray-resembling butterfish blends with the background surprisingly well, catching one’s eye only when it is moving. The numbers are fairly low, compared with the reports one hears from just a few decades ago. It’s a pity since this is certainly a fish one would like to know more about.

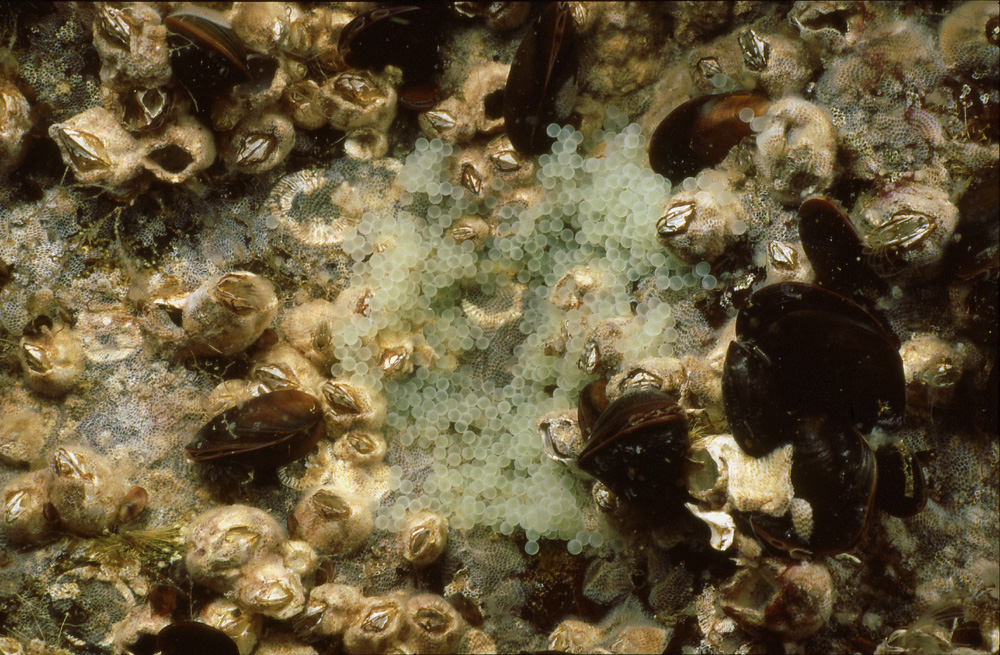

The bull rout is noticeably bigger and less spiny than the scorpion fish but otherwise they resemble each other quite a bit. The bull rout normally spawns in winter but in this case the male is guarding its eggs in April. Was it, that the eggs were not developing and the fish was about to abandon them anyway?

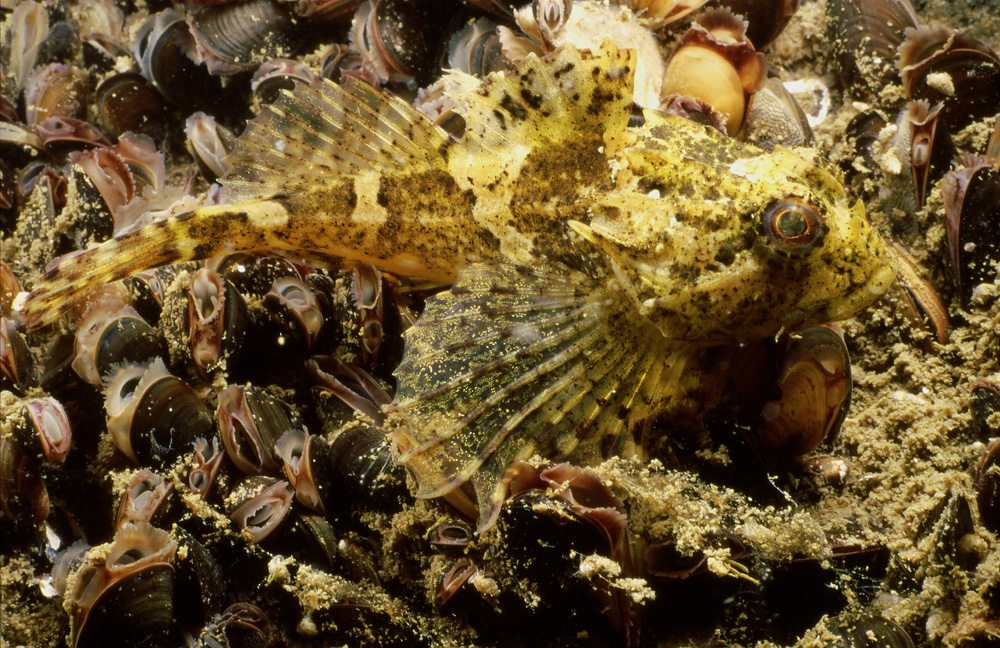

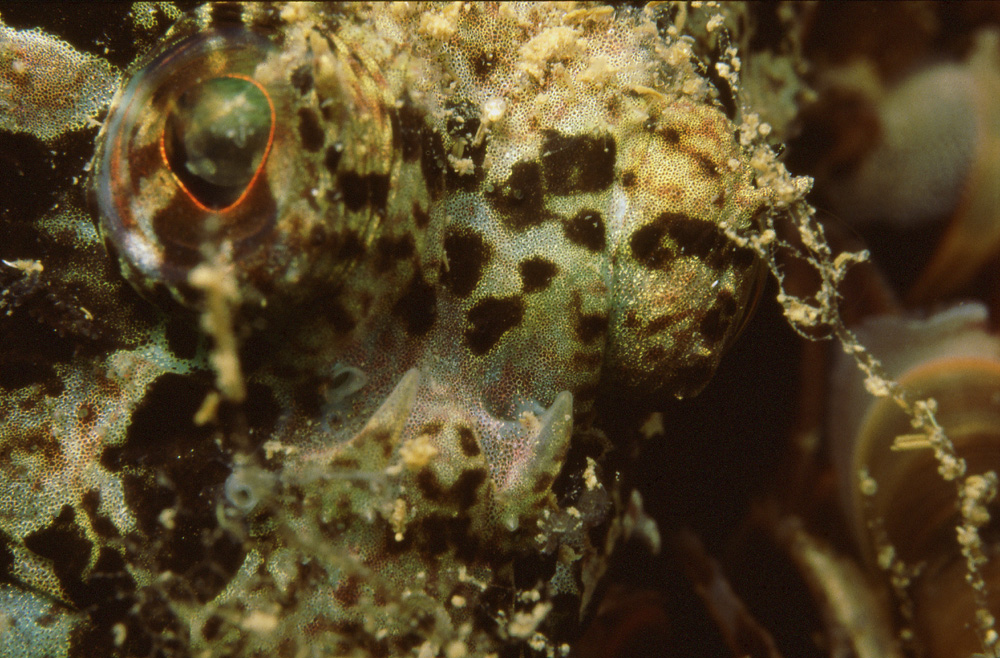

The scorpion fish is a master of disguise, with an ability to change its color to match the surroundings. It will mostly just lie on the shelves of the cliff or even hang upside down with the aid of its spiny fins. It is much more common in these areas of the Baltic and it spawns later than the bull rout but seeing it actually spawn or guard its eggs is rare indeed.

The cliffs are a possible breeding ground for the lump fish but its numbers, too, are so low that one is just delighted to see them at all. Not so with the viviparous blenny, which is a regular visitor. Its preferred habitats are boulders and the crevices of the cliff.

Any firm surface placed in the water will do as a miniature cliff. The sessile animals will try to take over all the surfaces, competing fiercely with each other for a place to grow on. A submerged log, and a polypropylene rope holding floating docks of a marina in place. Both of these locations are obviously well suited for the sessiles but the dominating species differ from the ones typical for the real cliffs, even for just the reason that the surfaces have not been available for very long. The sessiles on the log could be from anywhere on a typical cliff but the two colonial hydrozoans on the rope are flourishing in a way unseen on any natural substratum.

|

Lisää pääkuvan päälle tekstiä klikkaamalla ratas-ikonia,

joka ilmestyy tuodessasi hiiren tämän tekstin päälle.