7. GONE WITH THE GOBIES

There are around two thousand species of gobies in the world. Luckily, or unluckily depending on one’s view, there are only four in the northern Baltic proper; or used to be, because since the turn of the century the fifth, the round goby, has already been observed in the Finnish waters. For the purpose of this book we’ll just forget about the newcomer, though.

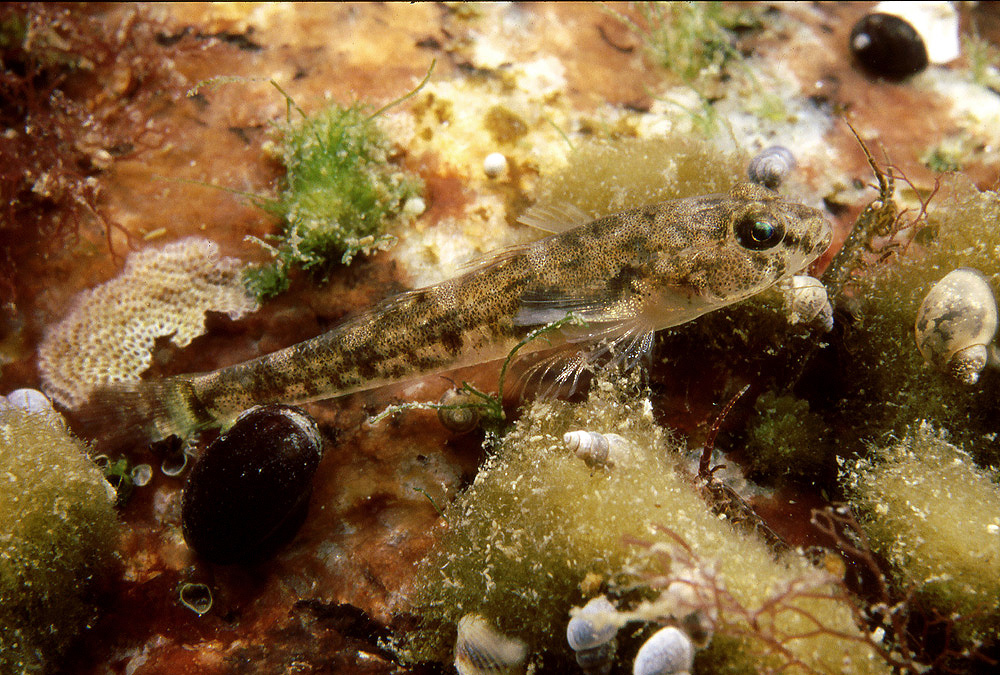

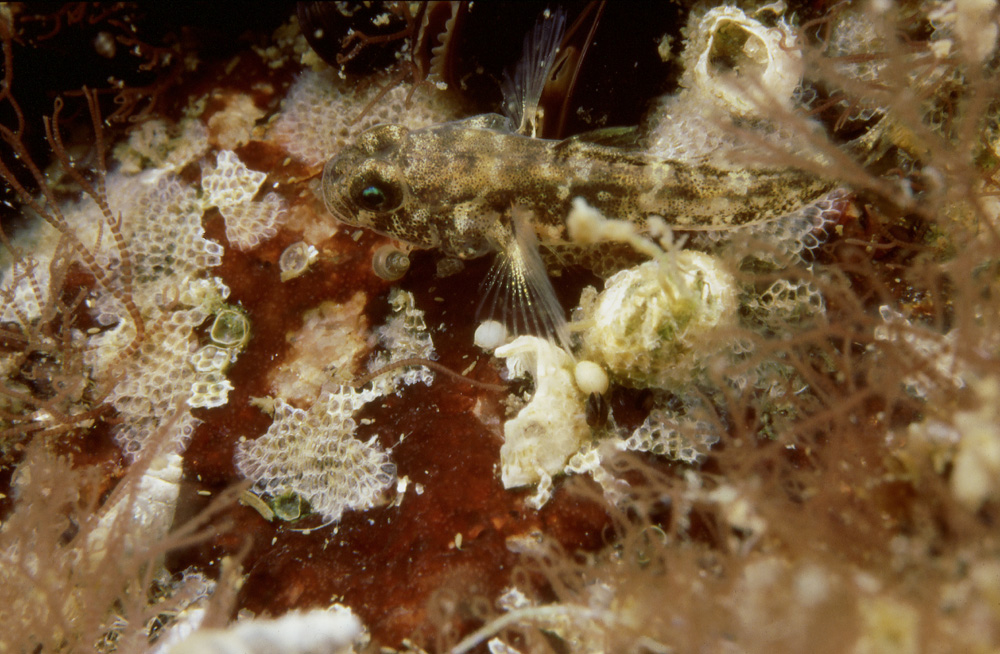

The common goby frequents the shallowest parts of the shores and is more fearless in its behavior towards a diver than a sand goby, which it otherwise very much resembles. Identification from the colors and markings is difficult but the common goby is usually also rounder in the head area. When either one of these two is lying on sand its identification is less certain and, in any case, only by using some kind of magnification and checking the decisive characteristics it’s possible to be absolutely certain of the species.

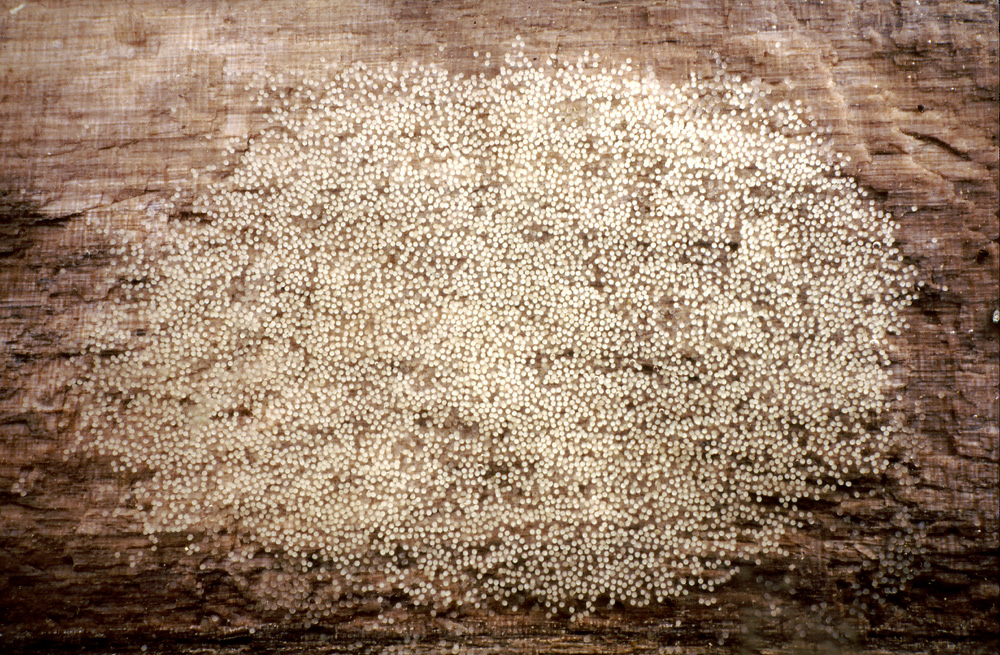

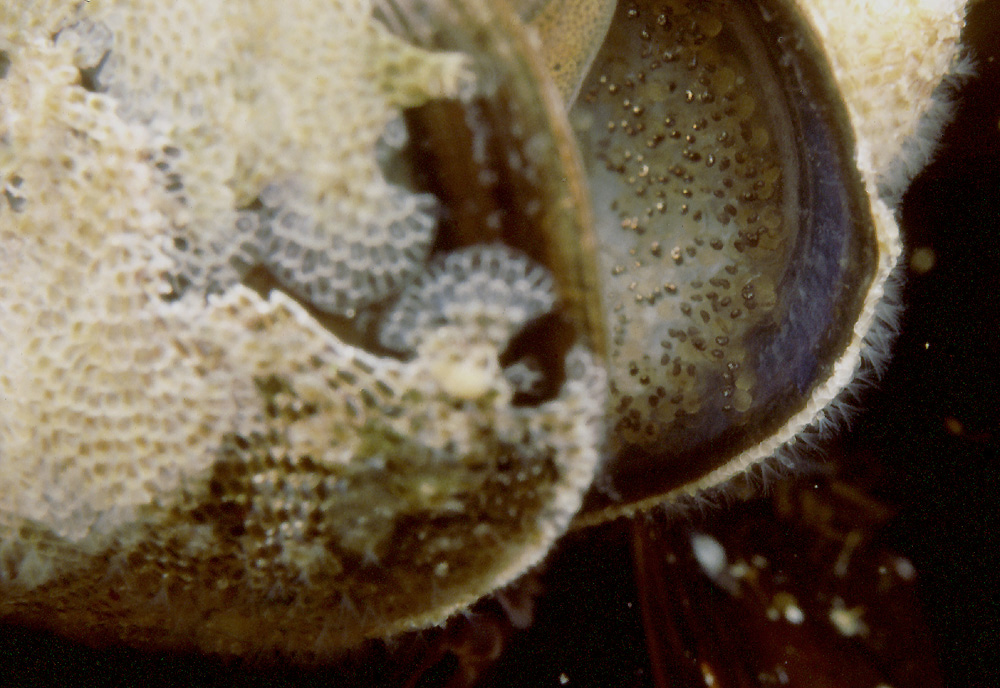

The sand goby also lives in areas where there are no sand gaper shells for nest building. A piece of wood, like here, will also do as a substrate to lay the eggs on.

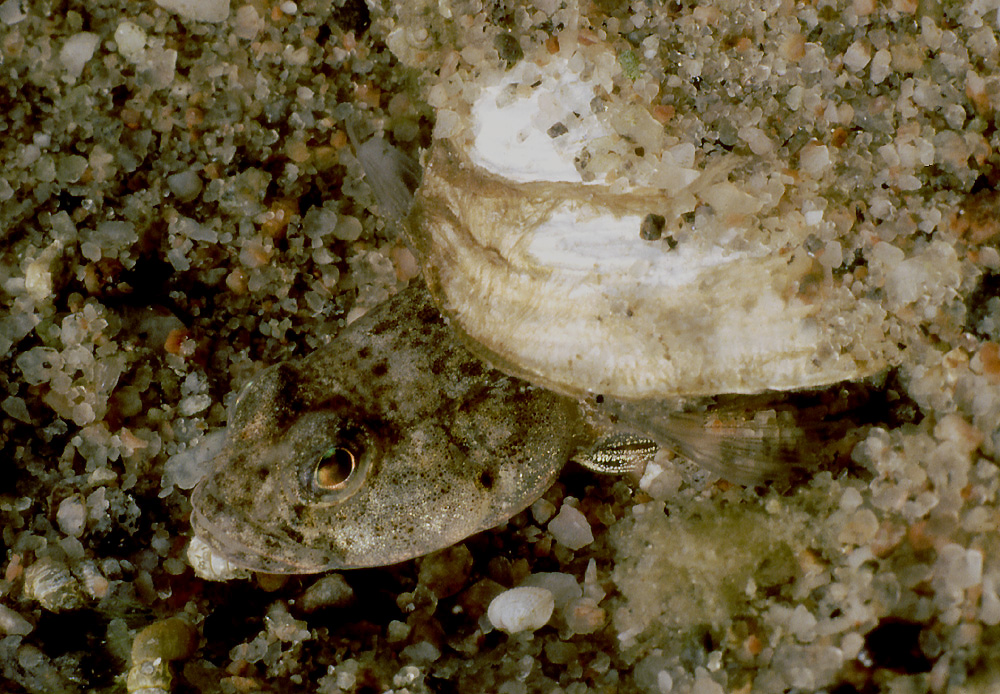

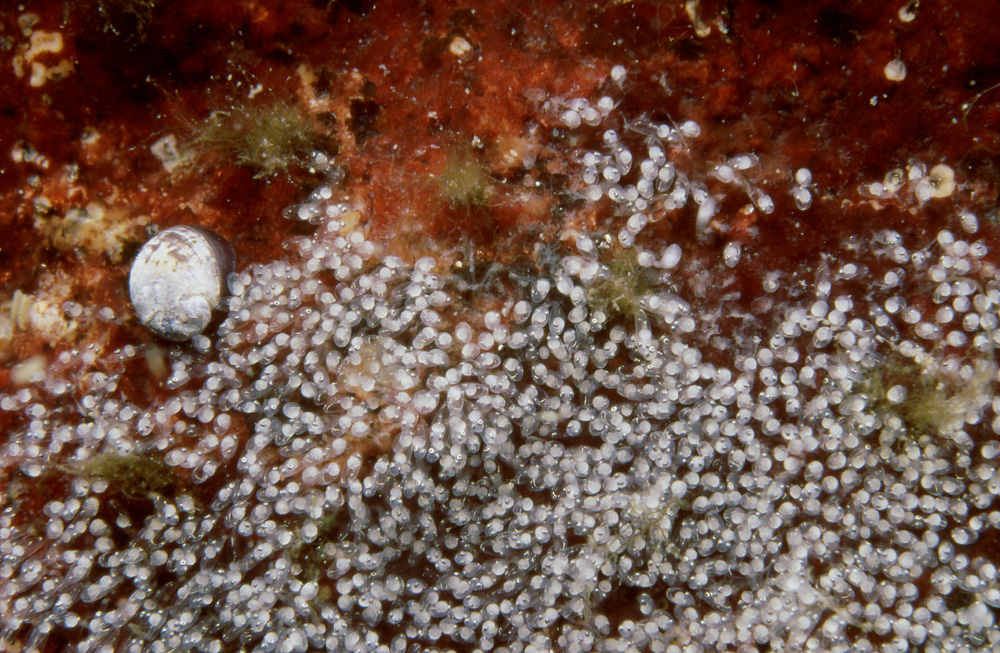

For the best reproduction success, though, the sand goby needs sand gaper shells, and, the bigger, the better. The biggest males tend to conquer the biggest shells and are the most capable to defend their offspring against intruders.

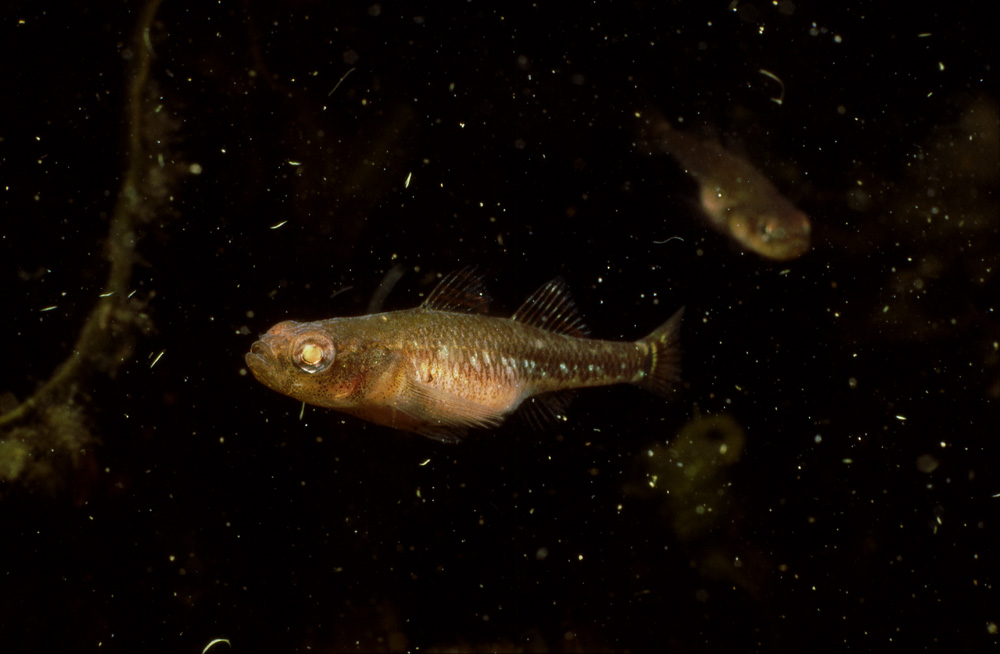

If there is a photographic legacy I’d like to pass on, perhaps it’s this: go and take this photo of the two-spotted goby males demonstrating for the right to spawn with the female, and do it with the camera at the right shooting distance. For me the situation was over too quickly to have time to bring the camera close enough.

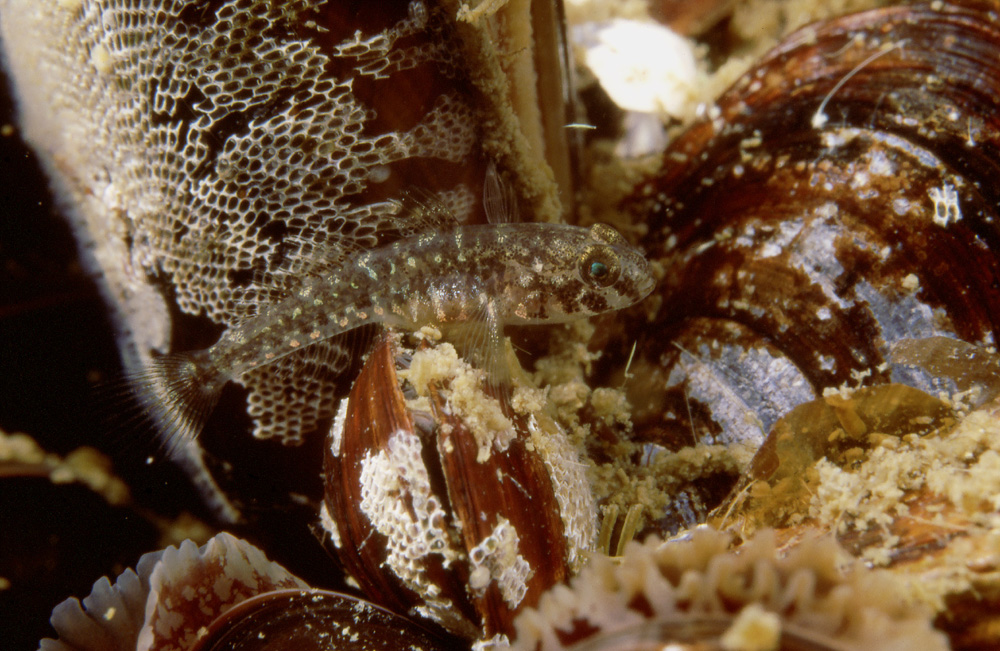

My observation is that when the spawning time is at hand the females gather in a group and hang around in areas where the males have enough empty mussel shells to build their nests of.

When the nest is ready and the female has visited it, the male keeps hanging around, and rests on the bottom nearby, swims around or aerates the eggs in the nest.

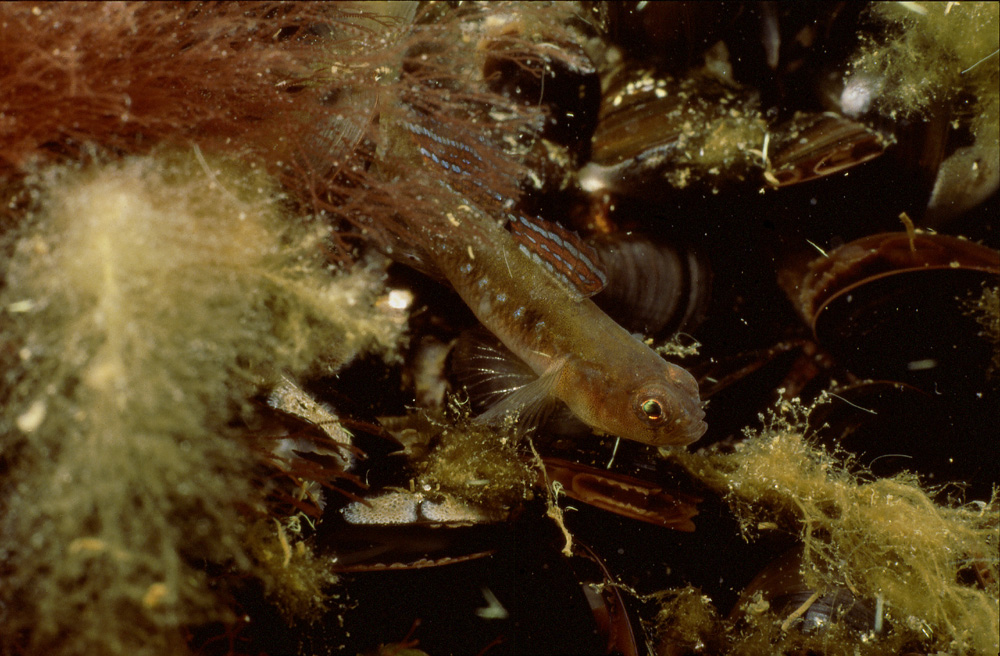

Juvenile black gobies are not as dependent on their hiding holes as the adults are. They tend to live in parts of the littoral zone where adult gobies are rarely seen. Typically, the juveniles move around in the shallower part of a rock cliff, in the little crevices formed by the sessile animals and even among the filamentous algae.

The urge of the typical black goby behavior is there from an early age on: this fish approaching adulthood took shelter in a mussel shell in the middle of a large area of sandy bottom.

At a later age the hiding behavior is all the more clear with even territorial tendencies. The black goby will hide in any hole available when feeling threatened but when the spawning period approaches, there is another reason for being interested in the holes: the fish lays her eggs preferably in protected openings of a rock cliff. It’s the duty of the male to conquer a suitable spot and protect the eggs.

Crevices and holes are the favorite spawning site but even a completely open surface of rock will do, if the better places have been taken already.

The round goby will soon be the biggest of the local gobies, no doubt, and will dominate the area it pleases but it will hardly be prettier than the black.

|

Lisää pääkuvan päälle tekstiä klikkaamalla ratas-ikonia,

joka ilmestyy tuodessasi hiiren tämän tekstin päälle.