6. A FACE IN THE SAND

A formation of three separate ridges runs across most of Finland south of the lake area, from the southeastern corner of the country first towards west, then west-southwest. The first and largest of the ridges, Salpausselkä One lies where the edge of the continental ice cover stopped some 10 500 years ago while retreating. The part on dry land of Salpausselkä One ends where the town Hanko lies, east of the Archipelago sea, but the signs of the other two, notably Salpausselkä Three, can be seen in the area that is the main target of this book. The example beyond all the others is the island of Jurmo in the middle of the southern limits of the area.

When the ice stopped, it allowed the melting waters to sort the stony material created by the grinding of the ice by its pebble size. The sandy areas created in these processes can be seen here and there on the map as forms peculiar to sandbanks.

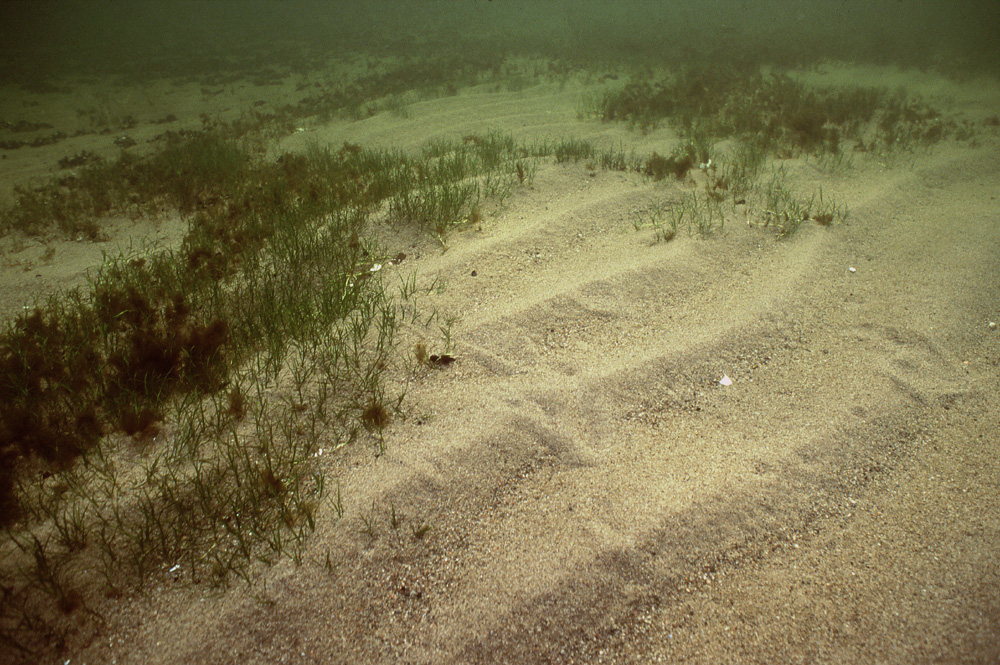

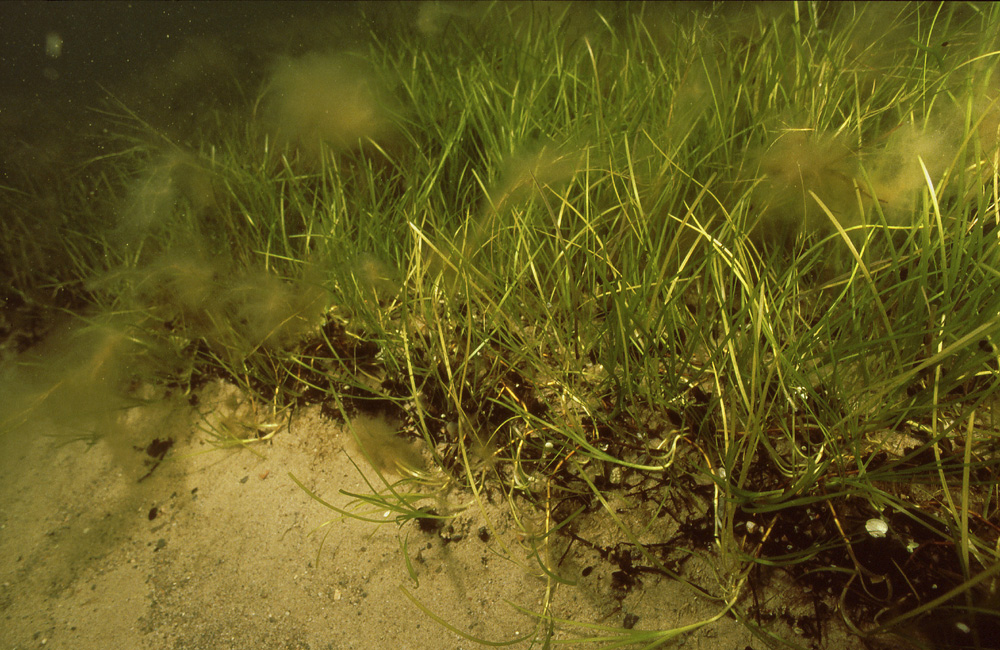

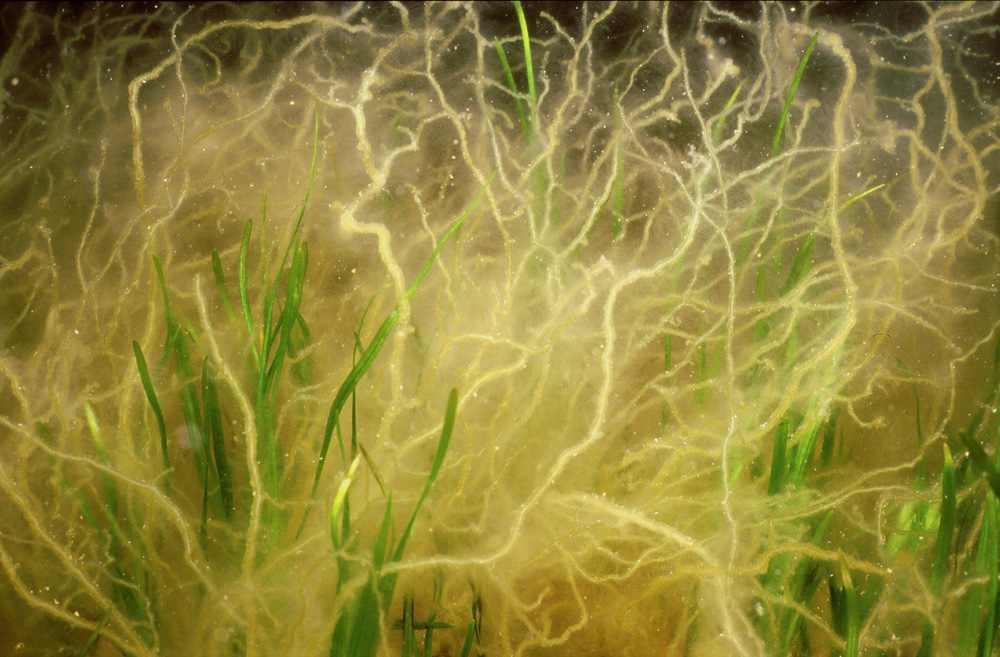

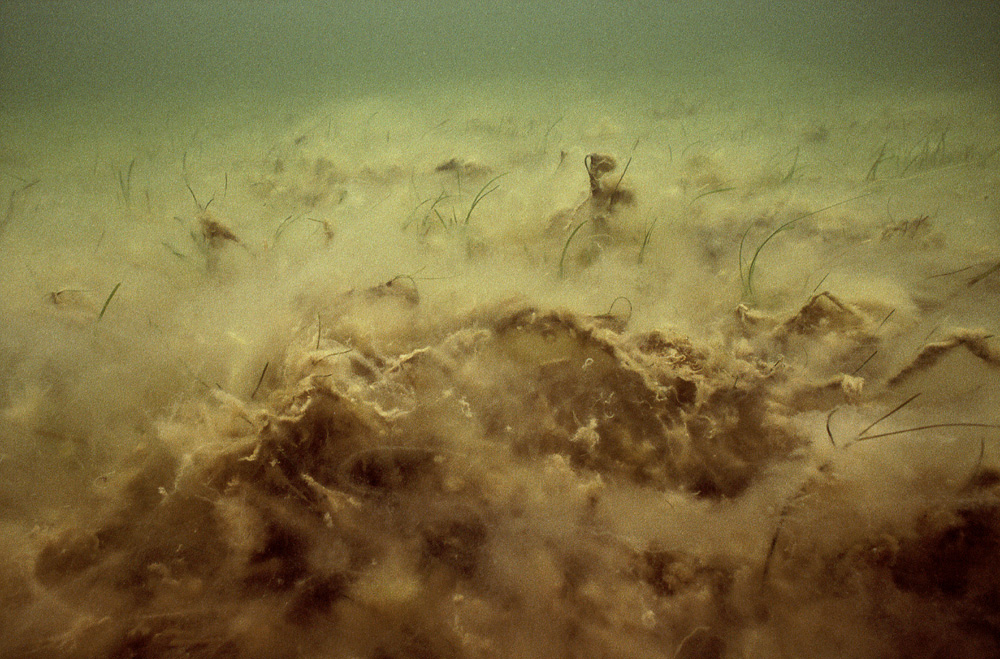

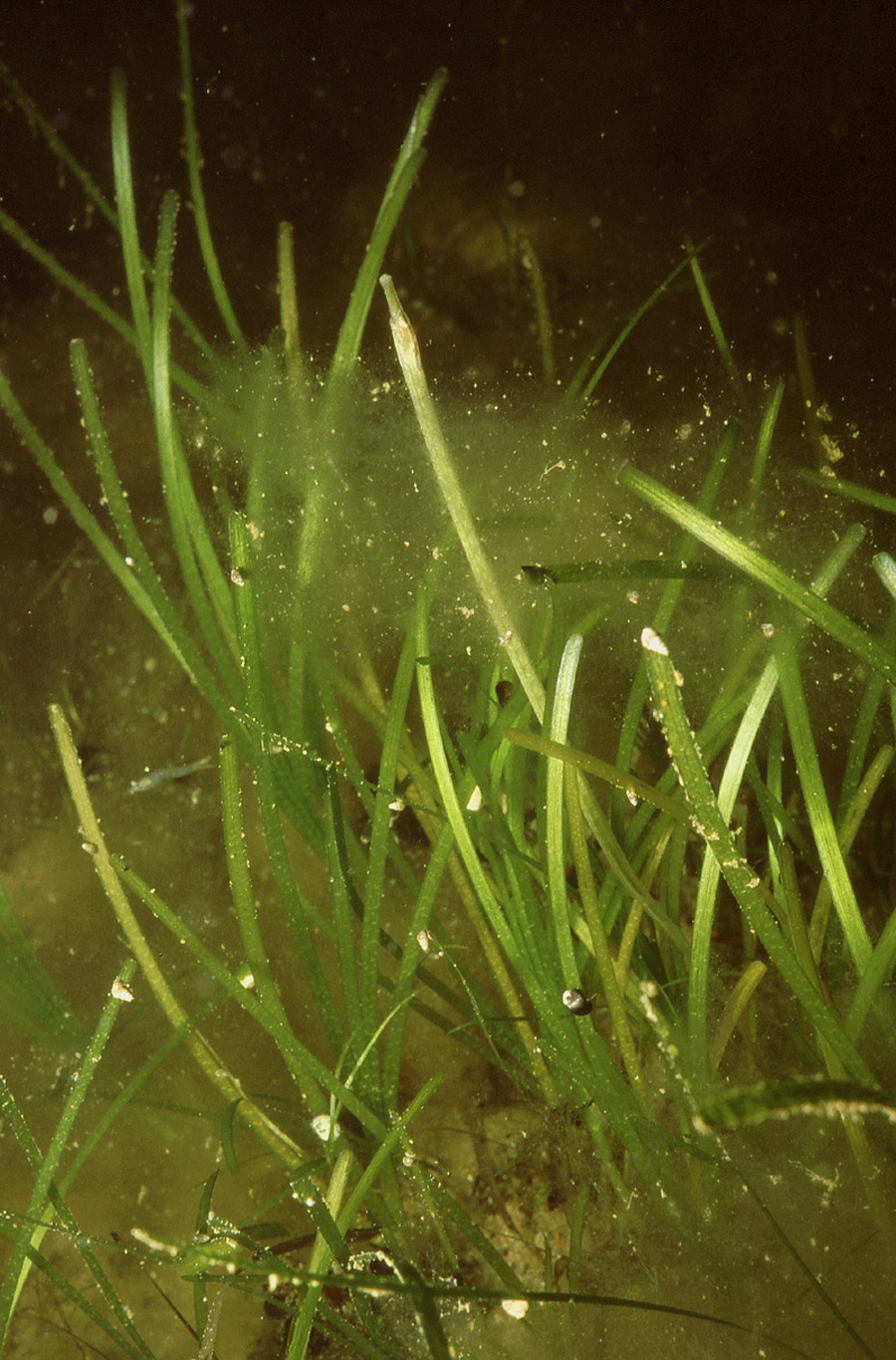

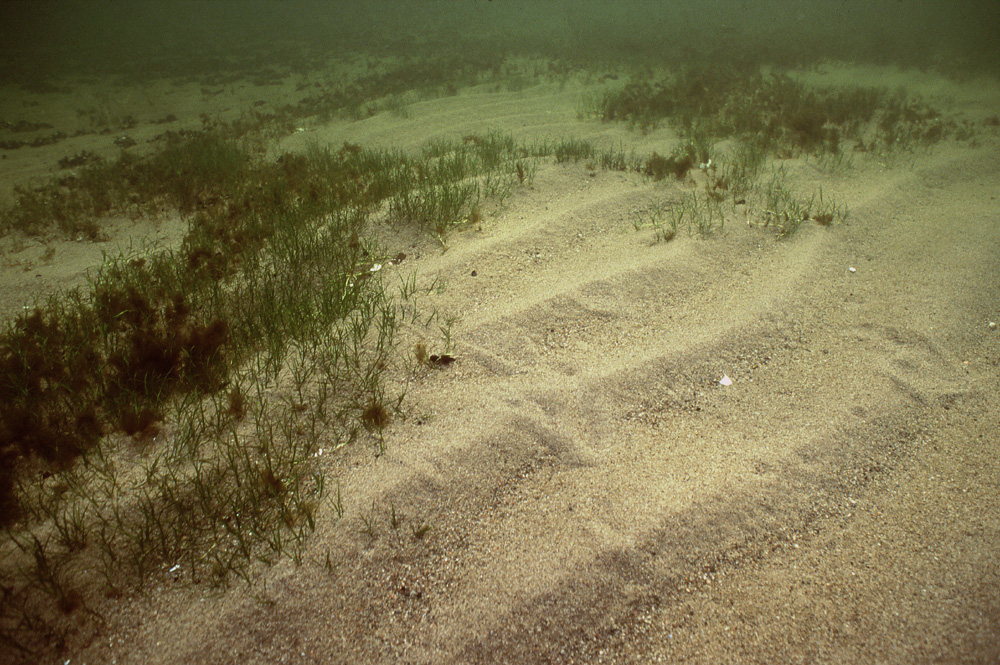

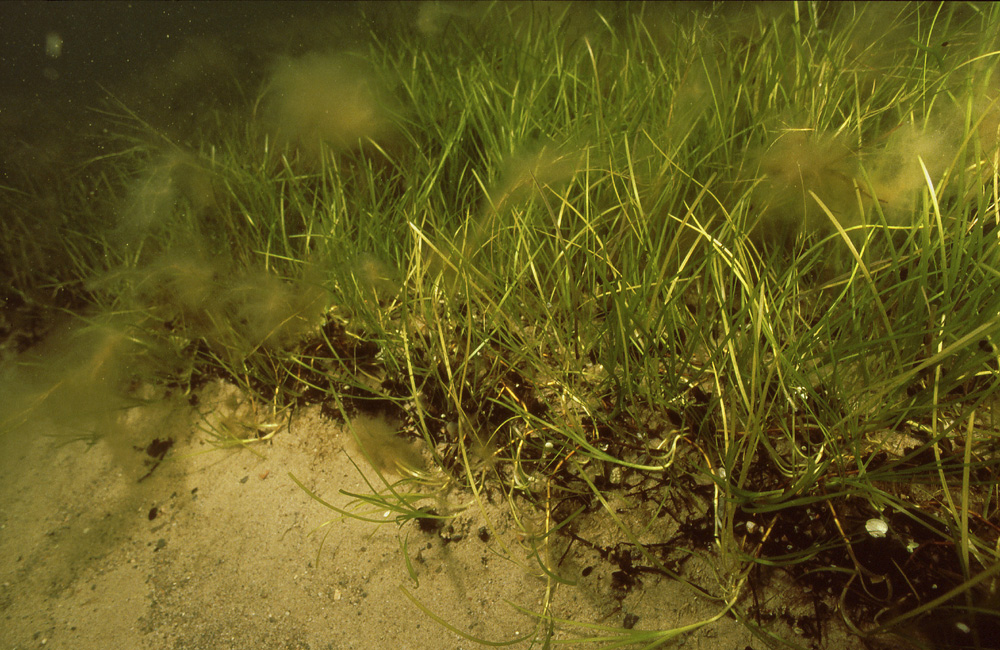

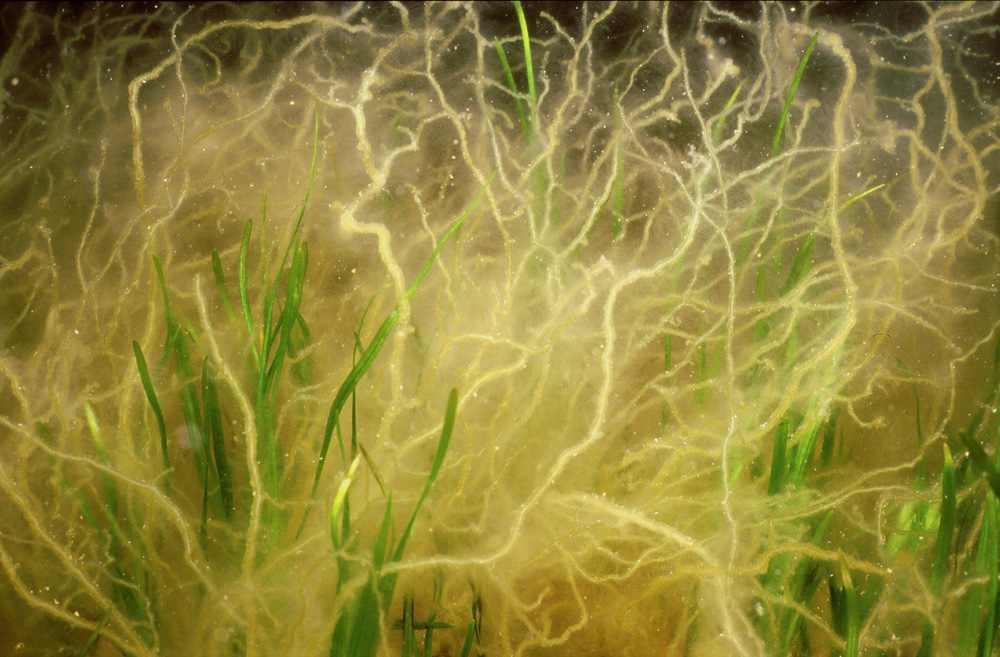

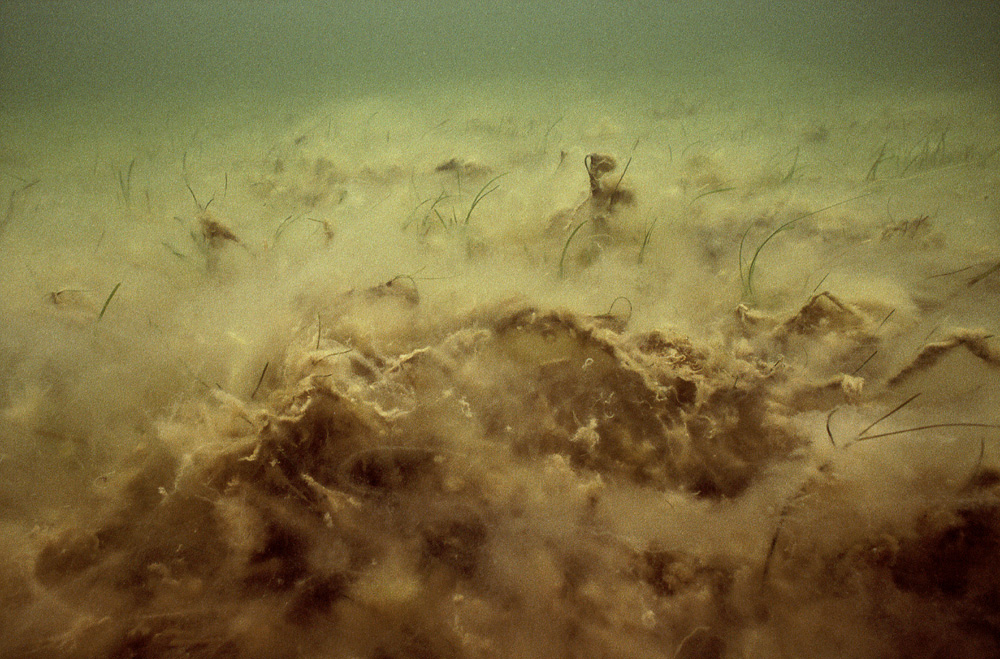

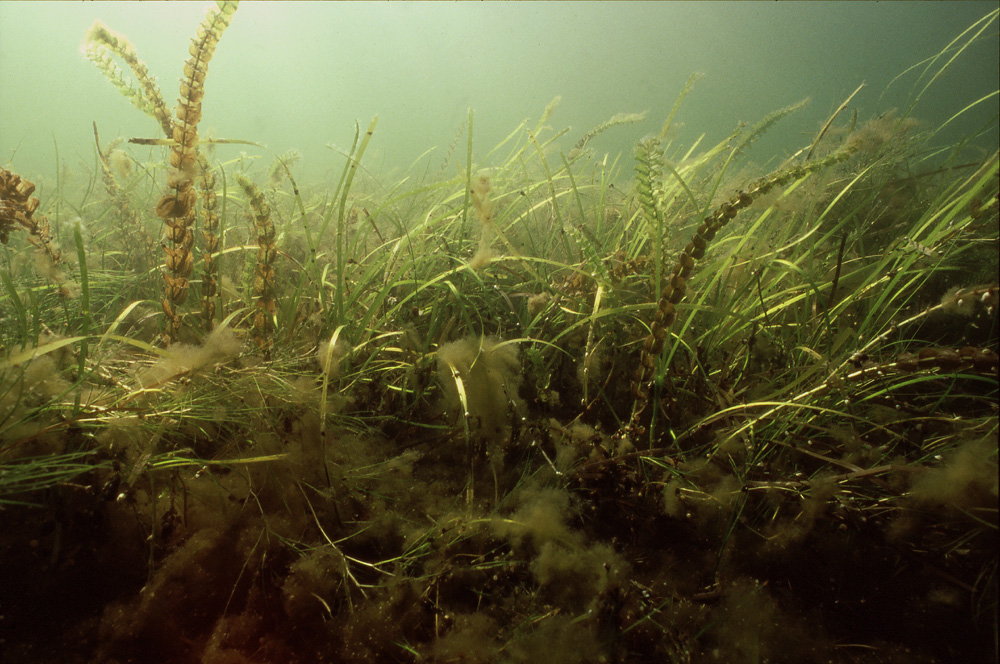

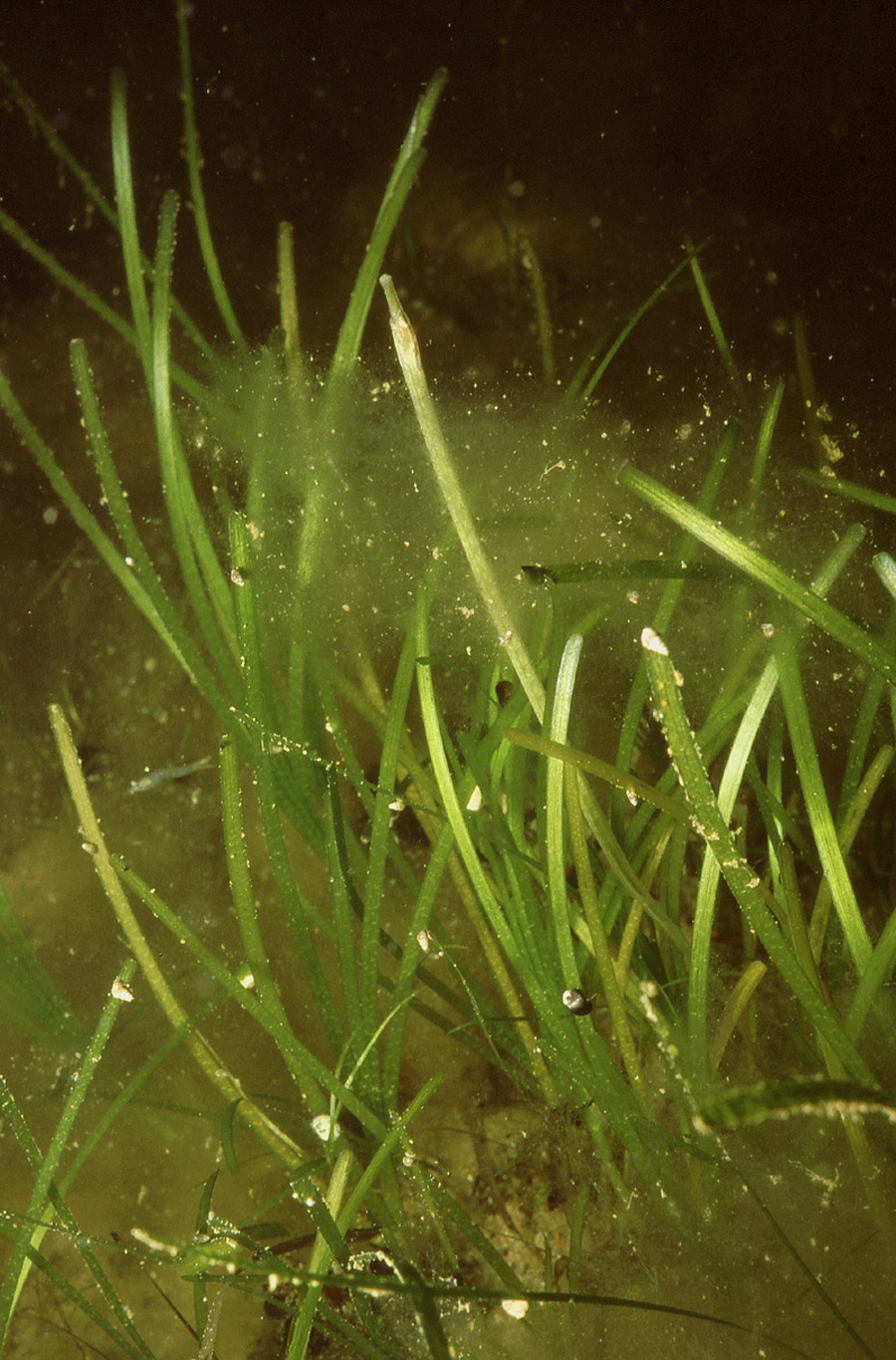

The sandy bottoms in their purest form are unstable, prone to change shape and place under the workings of waves and currents. This is challenging for both the vascular plants and animals living in these environments and they’ve had to make various adaptations to cope with the conditions. The plant most adjusted to this type of life, eelgrass, will only grow in depths where it is able to resist the forces of the waves and still has enough light to grow, in other words from around three meters down to six meters in depth.

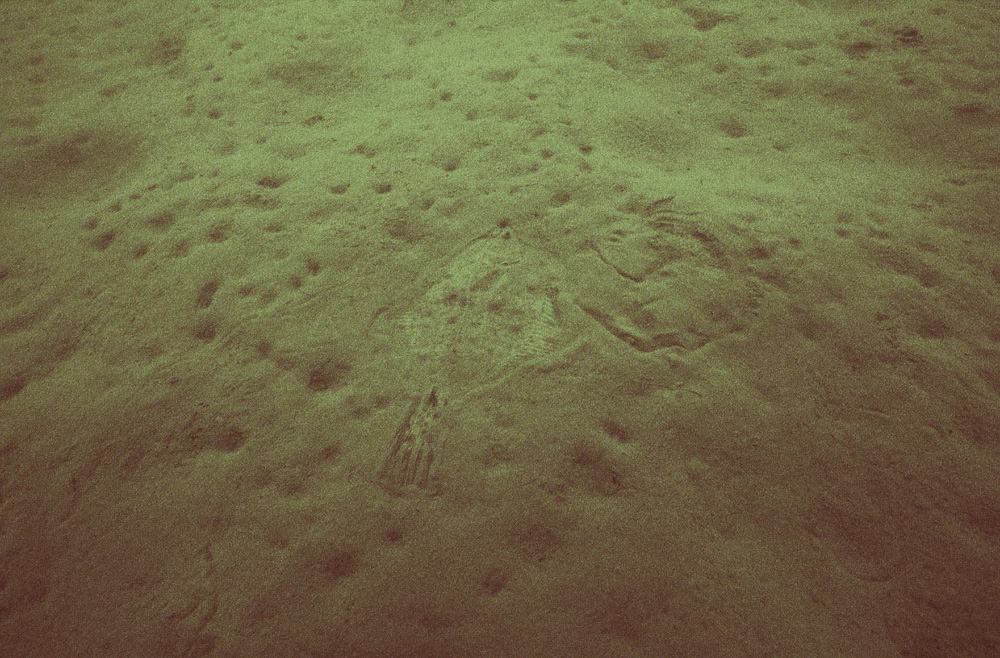

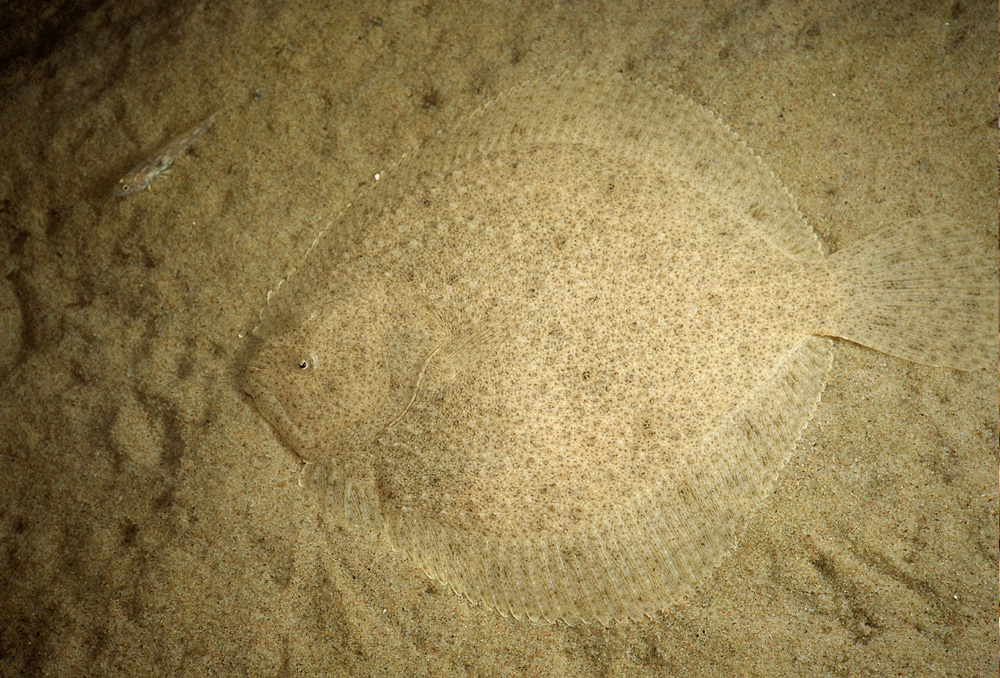

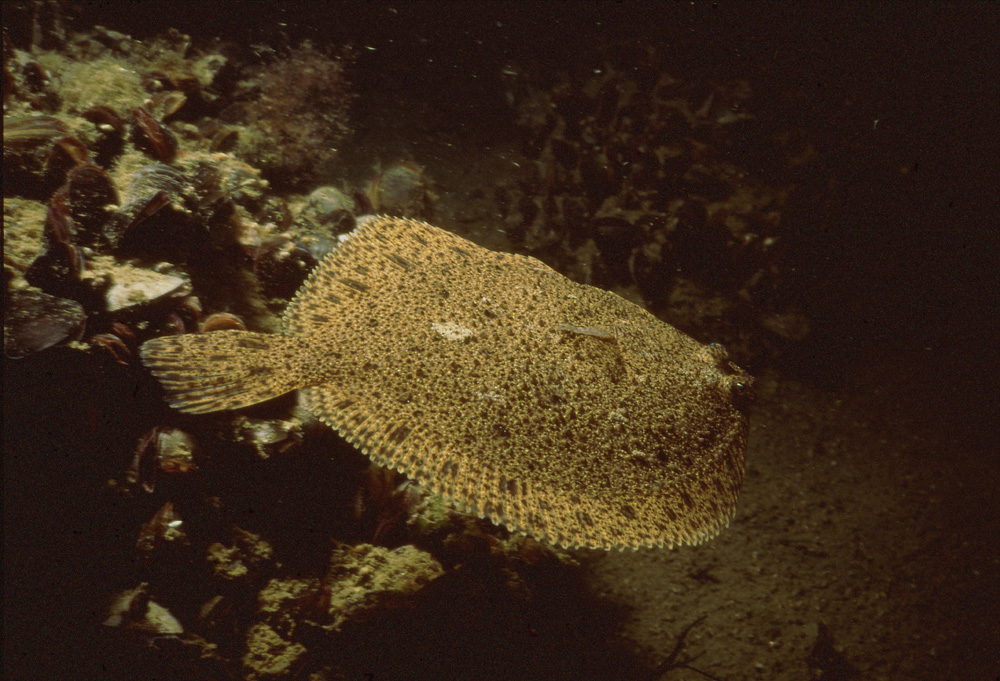

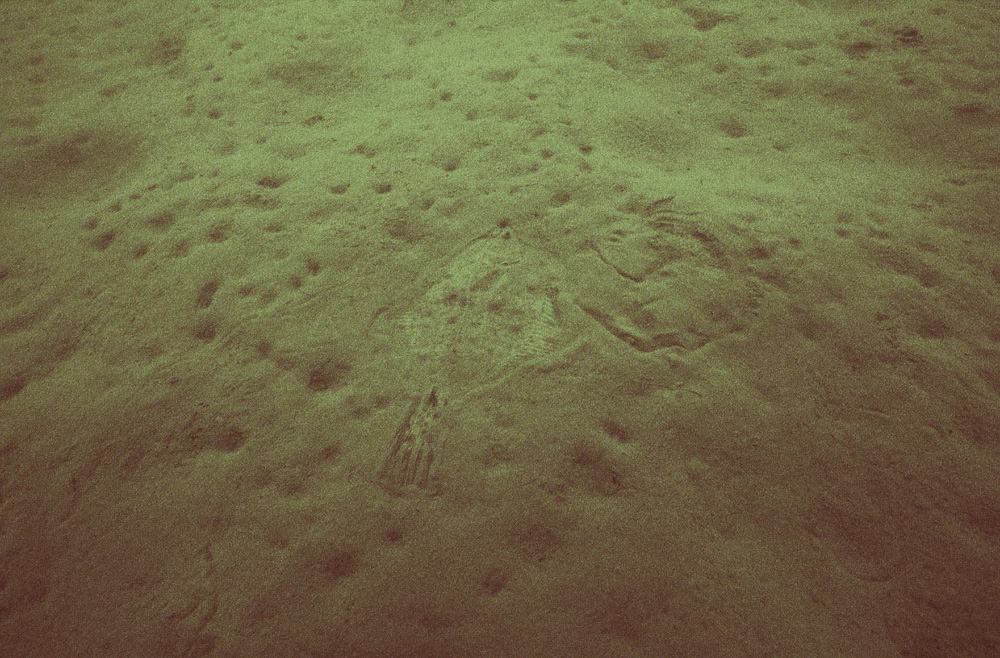

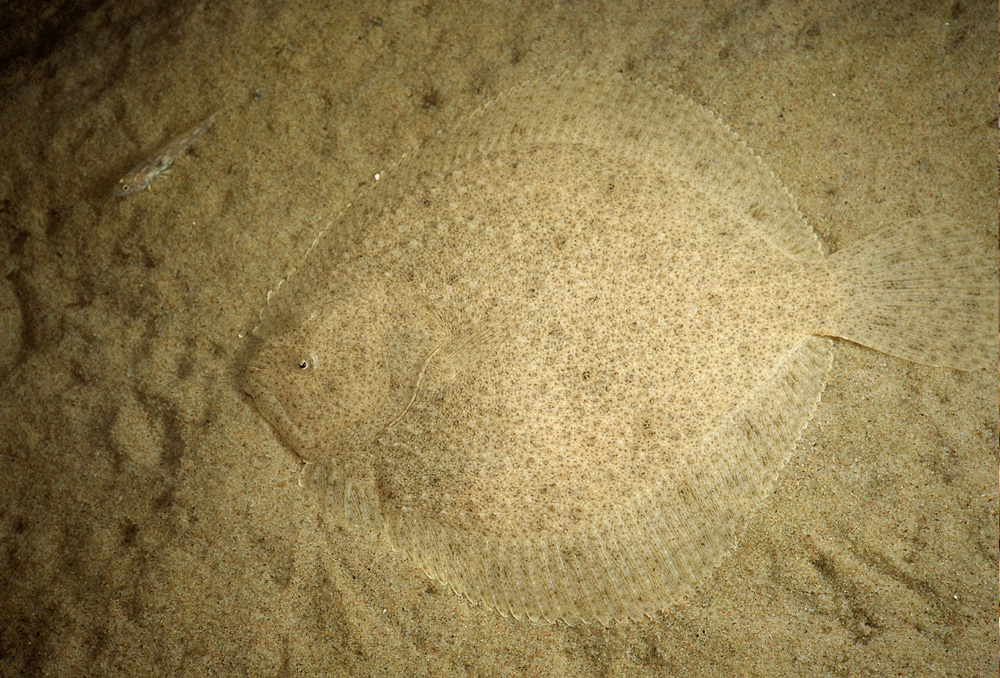

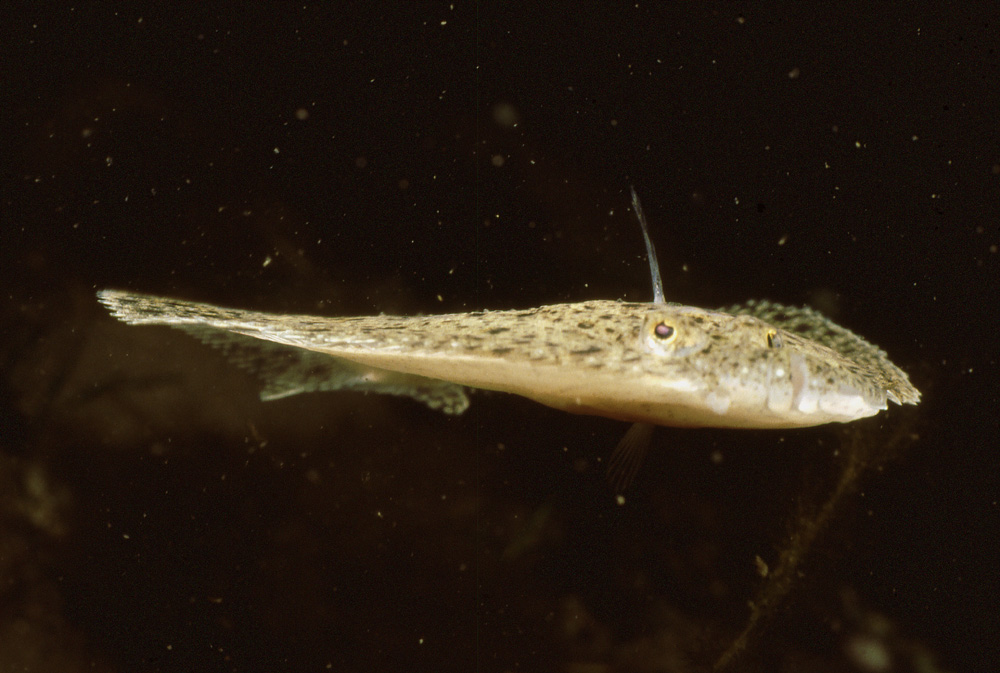

In the environment devoid of places to hide the animals have two major choices of adaptation, either to blend with the surroundings or burrow into it. The animals can burrow permanently, like the bivalves and worms usually do, or burrow for the day, like the common shrimps, and move around at night when the predators are inactive. The flatfishes burrow just enough to be covered and invisible to their predators and prey. The common goby and sand goby may also burrow partially at times, but it's when they build their nest that they become major constructors of the sandy material.

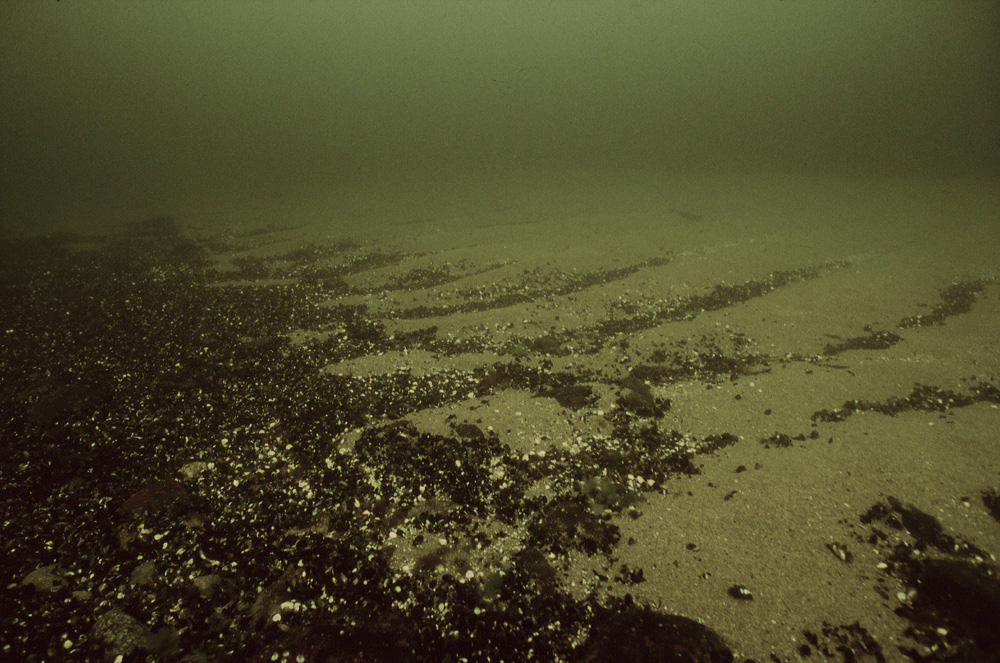

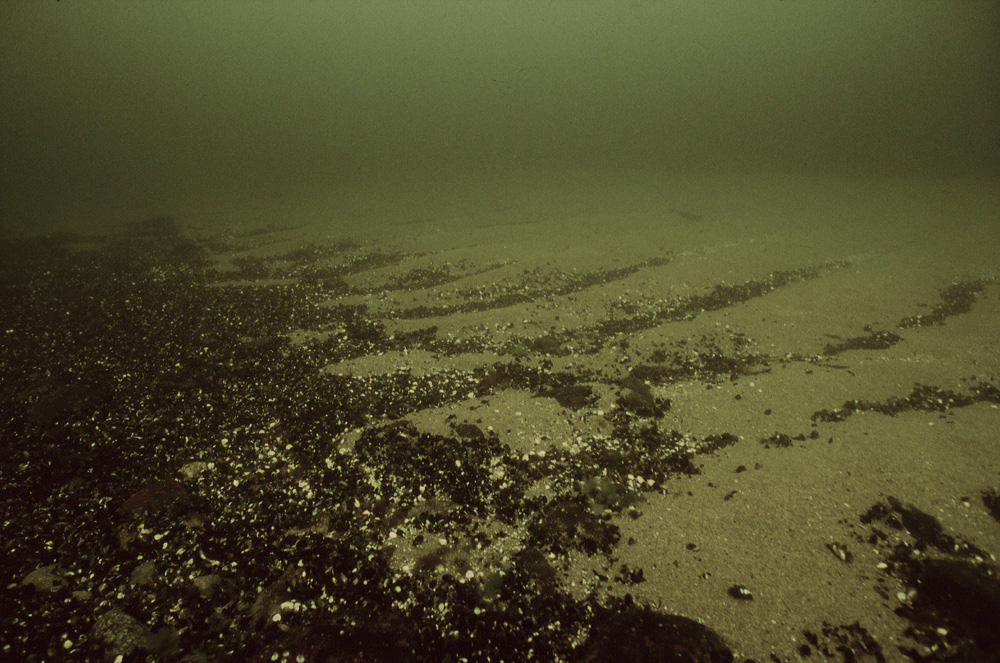

Sand in the sea tends to move from one place to another restlessly just like the sands of a desert. The currents and waves pile sand into dunes especially in shallow water but in the more open waters traces of wave motion, in form of dunes, can be seen to a depth of several meters. The dunes can move back and forth, disappearing altogether at times, but the end result is that the sand stays wherever it is now, since it's been subject to the present conditions long enough and the wanderings tend to cancel each other out. Finally, in greater depths pure sand bottoms are rare: the bottom material is finer and keeps accumulating since there is hardly any movement of water at all.

A sandy bottom at night, in an area protected from the winds: the stickleback fishes are mostly inactive but the two common prawns have come out for feeding. For the viviparous blenny it’s just one of its living environment.

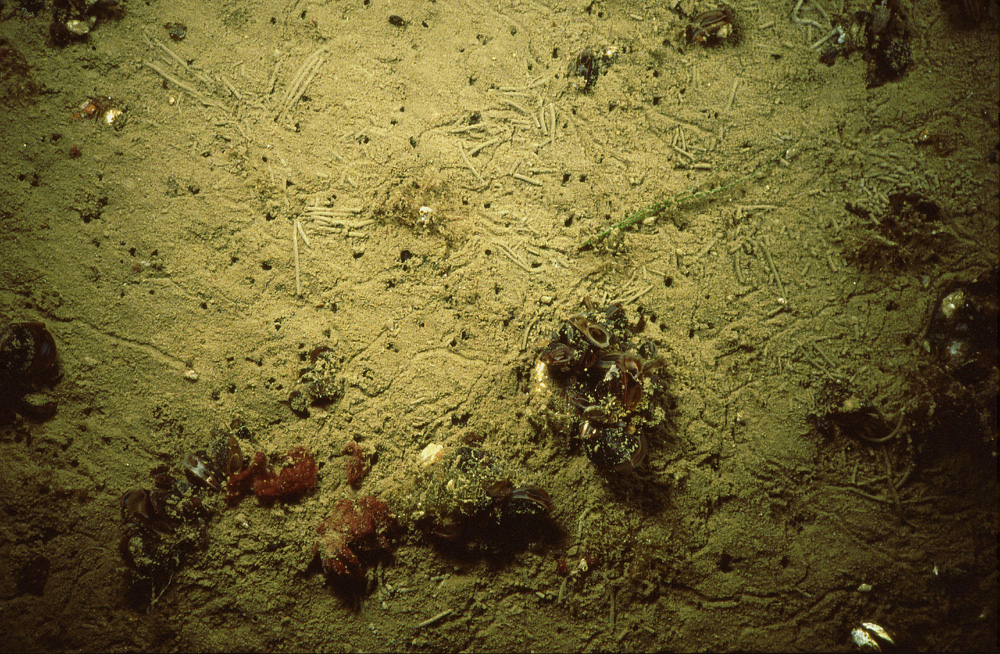

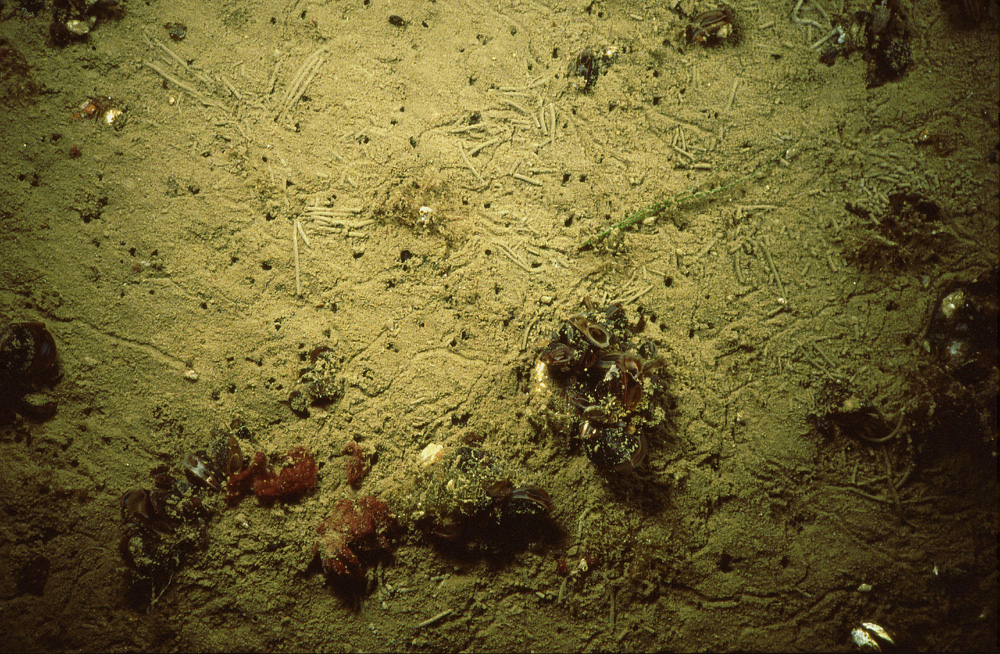

In slightly deeper water finer organic matter is already starting to accumulate on a sandy bottom. The burrowing life leaves its marks on the surface, mainly the excretions of various worms in this case. Tracks of shells, indicating accumulation of organic material the shells feed on, can also be seen. The mussels are actually attached to pieces of rock in the sand.

If digging a bit deeper into the loose bottom material, another sign of organic matter, blackening caused by anaerobic bacterial activity, can be seen: the sandy bottom is pure only in shallow water, under the influence of the waves. Besides the burrowing “tunnels” of worms there is a siphon of a sand gaper in this photo.

Worms are typical burrowers in any kind of soft material. An oligochaete and two polychaetes, genera Nereis and Marenzelleria, are shown in these three photos. Although the nereis, or common ragworm, does not live in a tube like some of the other worms, it does excrete a tube-like slime formation when moving around. The marenzelleria, being a deep burrower, is rarely sighted but it has already spread out widely onto the coasts of Finland even though it is a recent immigrant.

The sand gaper needs a bottom, which is soft to a depth that will accommodate its larger size. When disturbed, it will retract its siphon as much as possible, which means that part of the siphon remains visible. It will soon try to burrow again using its foot and when at the right depth, only the twin opening of the siphon remains visible, level with the surface of the substrate.

The lagoon cockle has only a pair of short siphons and cannot burrow very deep. Although not usually moving around actively it can do so at will. For the isopod Saduria entomon both walking on the bottom and burrowing are part of its usual behavior.

The common prawn is active at night and hides in the soft bottom during the day; or, when being threatened, even at night. When it’s in a hurry even a bottom lacking oxygen will do temporarily. When it’s got its claws into a tasty meal, like a whole dead fish in the last photo, it will defy its destiny and not let go of its livelihood.

Besides frequenting the most shallow parts of the shore the common goby has the same kinf of a close connection with sandy bottoms as the sand goby also has: it builds its nest by digging a cave under an empty bivalve shell, preferably of a sand gaper.

The flounder is normally right-sided, meaning its both eyes are on that side. Exceptions are common, though, as can be seen on these photos.

That there is enough food, mainly bivalves and small invertebrates, available for the flounders is a thought that unavoidably comes to mind seeing them lie on the bottom after a successful feeding. It could be that their habit of hiding in the sand is more an adaptation of avoiding being preyed on than preying on others. Be that as it may, at its best the flounder shows an admirable mastery of the art.

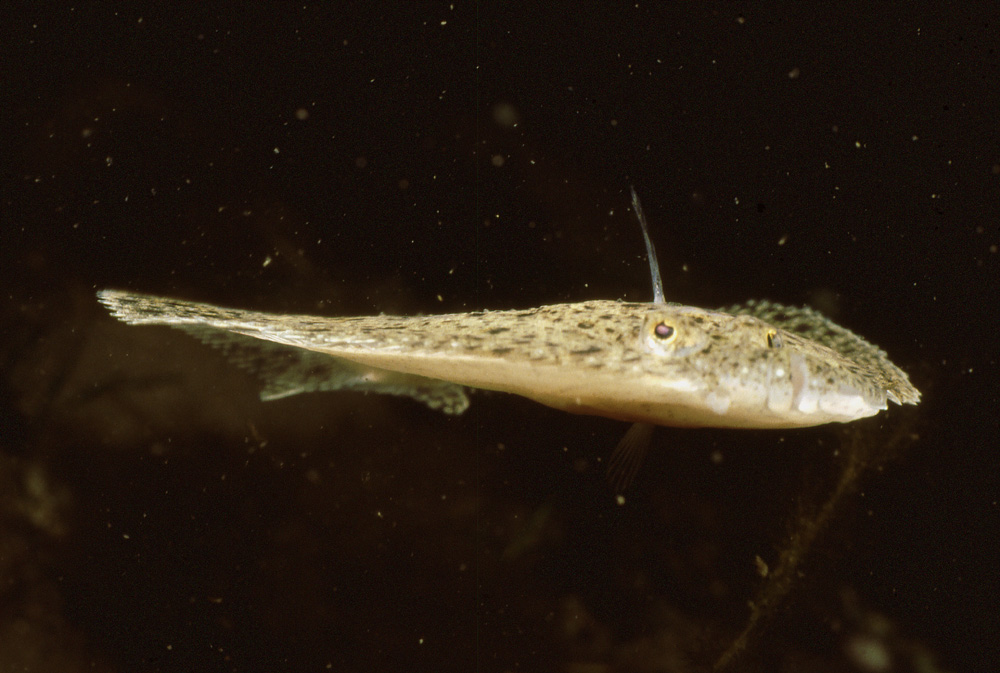

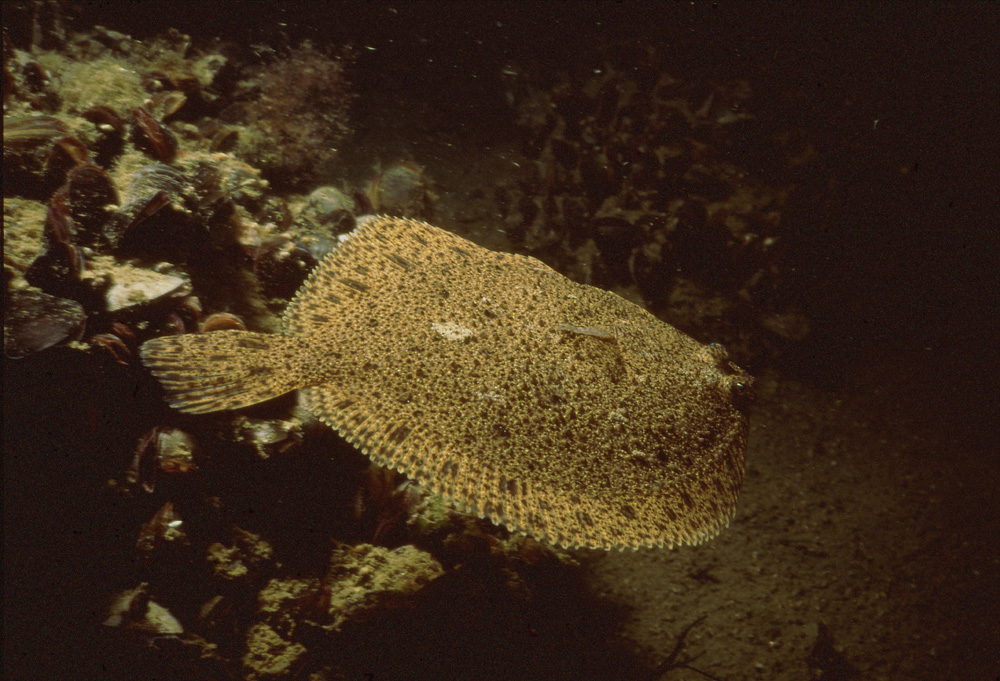

The turbot has its eyes almost invariably on the left side. It’s less common and the fully grown specimens one only rarely sees in shallow water. It’s clear from the impressive mouth and sharp teeth what the turbot’s feeding habits are: its main catch is made of fish, including such species as Baltic herring and sand eels. To catch them it will have to be able attack without a warning and be a fast swimmer.

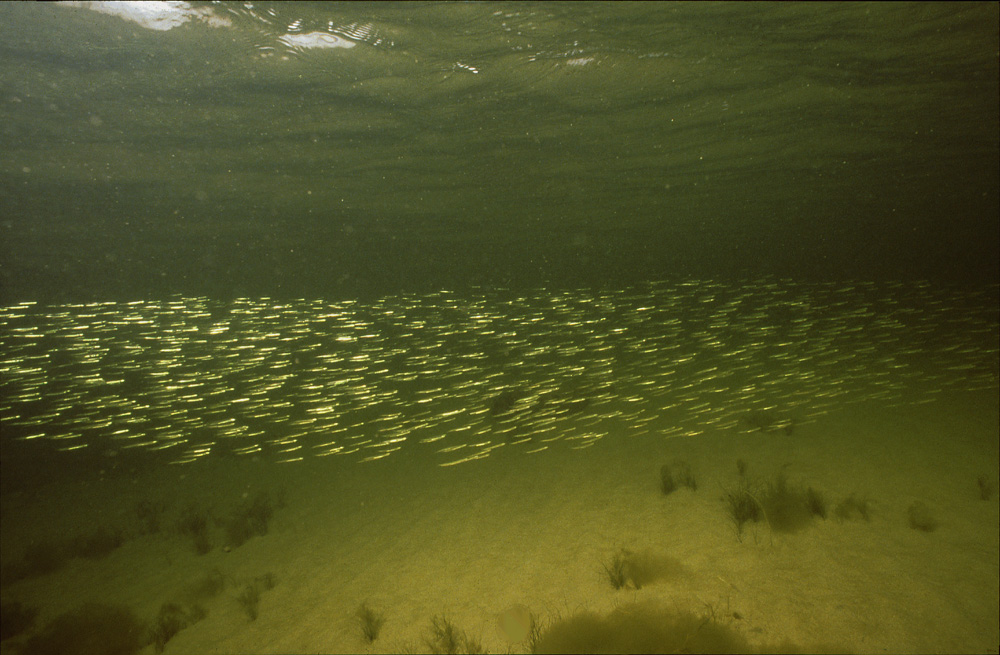

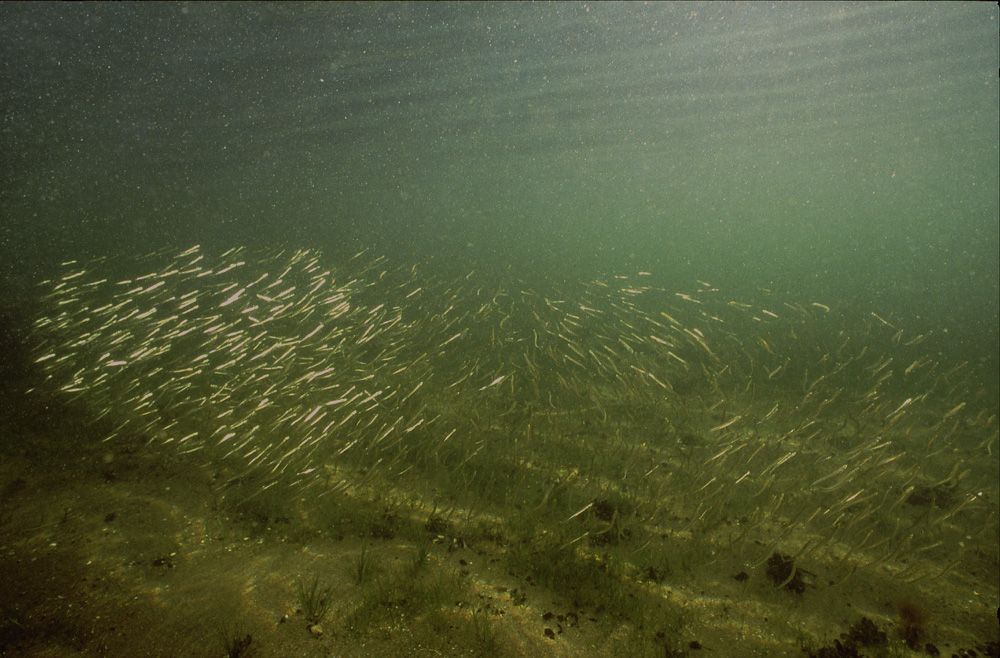

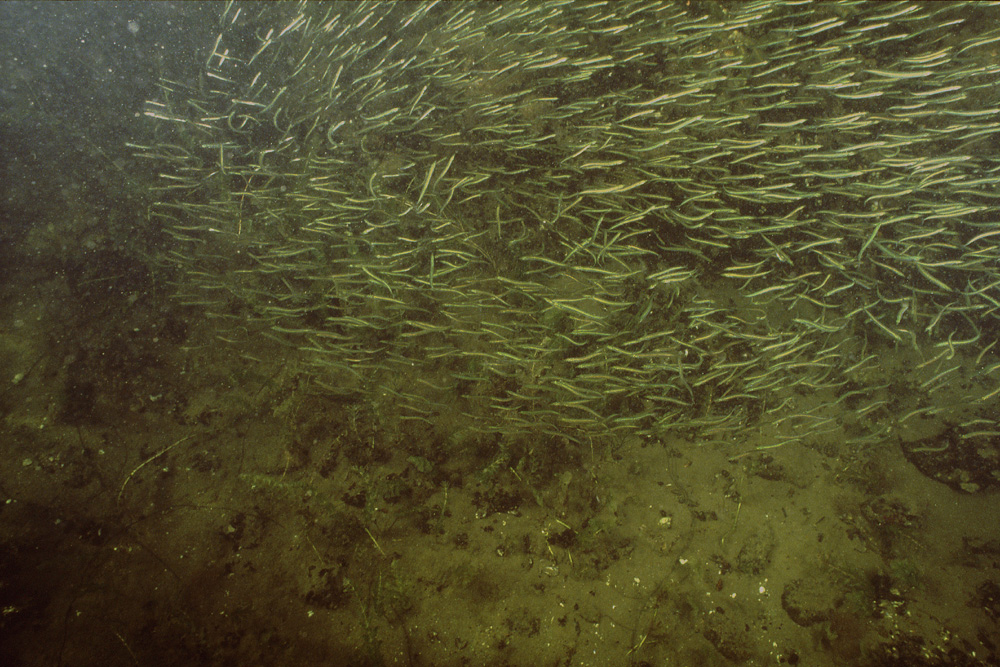

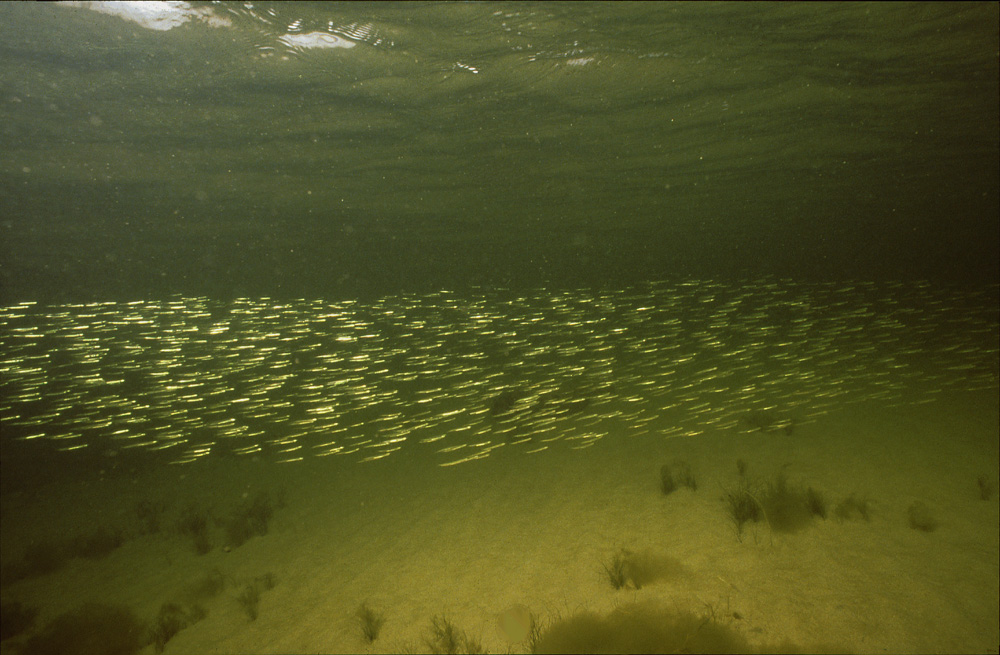

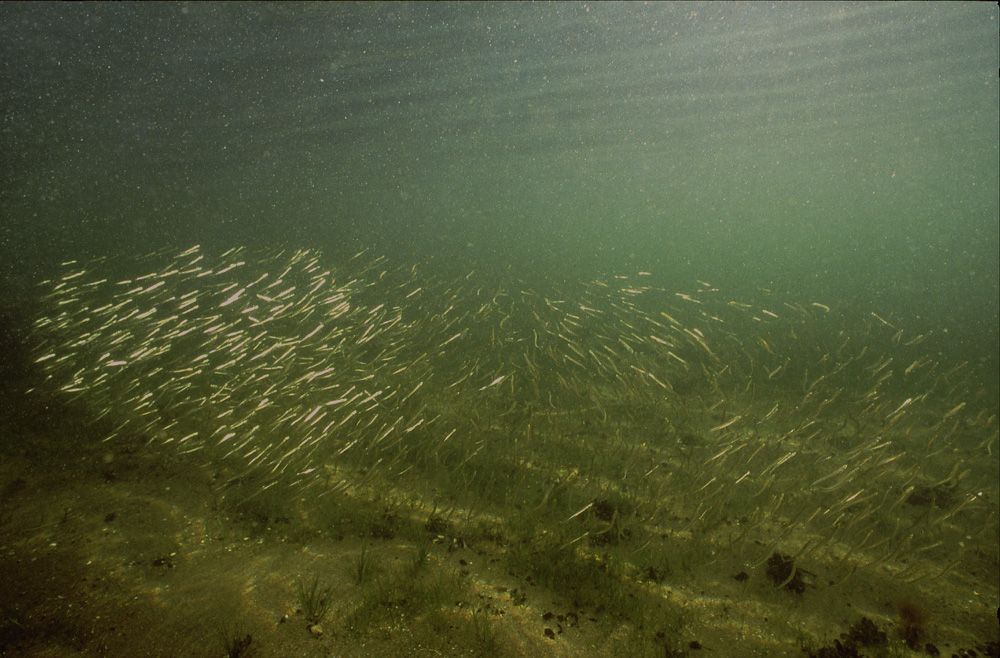

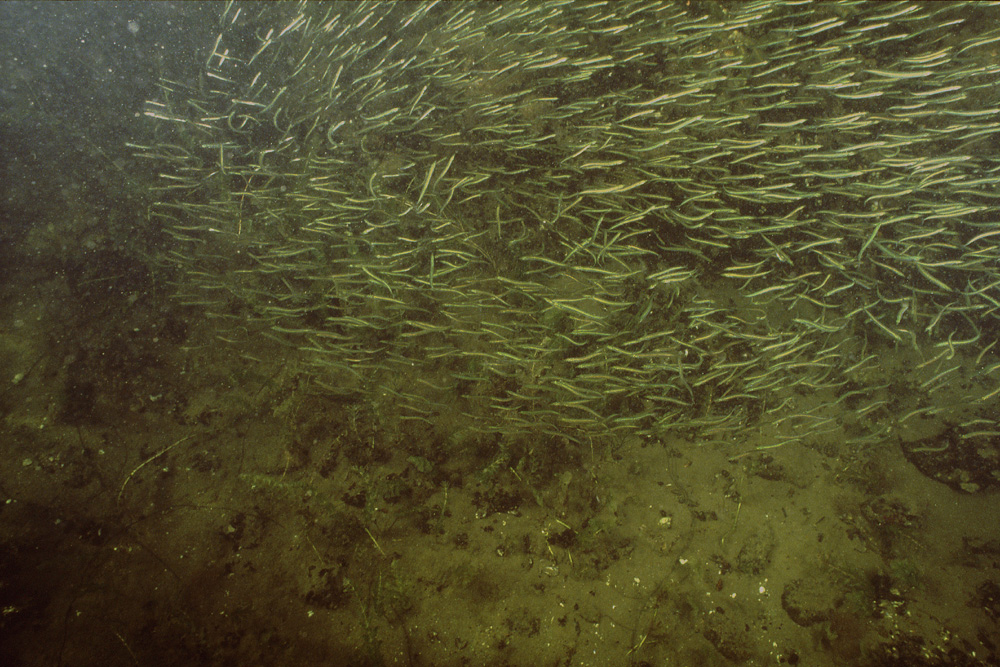

There are two species of sand eels in the northern Baltic proper, the lesser being more abundant than the greater. They resemble each other in appearance and sometimes greater sand eels mingle with the lesser and feed on them. The way to differentiate them by eye is their size, otherwise their behavior, too, resembles one another. A school of sand eels changes shape constantly, swimming in unison when feeling threatened and loosening formation when feeding in a leisurely manner.

The schooling habits of the sand eels could be of any species seeking shelter in numbers but the sand eels have their unique predator avoidance tactic of burrowing in sand. When a school of sand eels decides that it’s time to go hiding, they disappear in sand in a twinkling of an eye. Their secret is in the pointed shape of the head and lots of loose sand on the bottom.

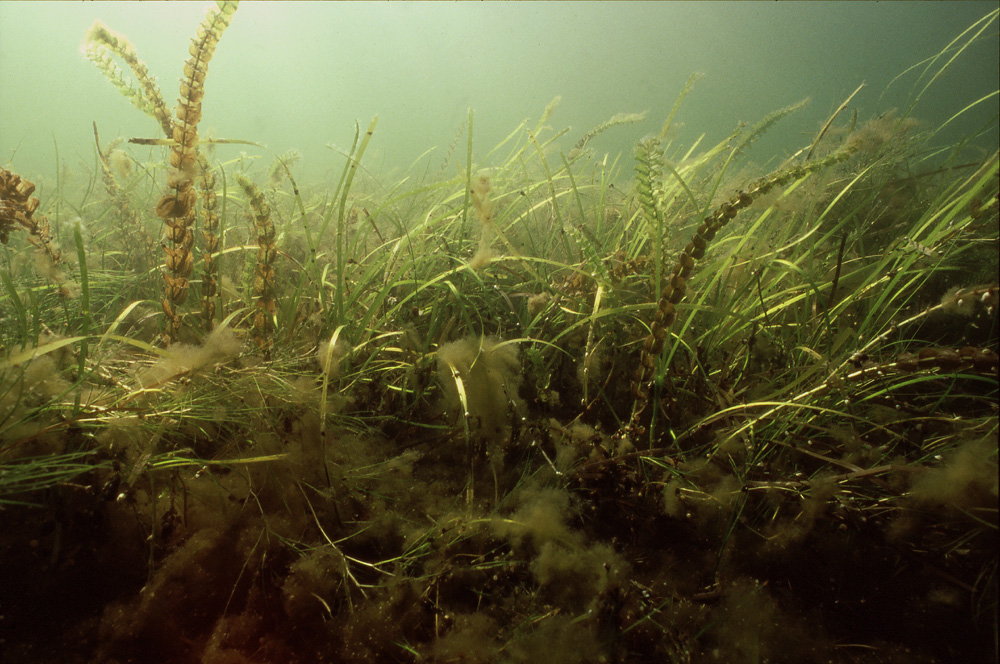

The eelgrass has a tendency to form a carpet of vegetation holding the otherwise freely moving sands down. Filamentous algae are a major threat for the eel grass, either growing fixed or drifting around in great masses. One of the ways in which the stress to the eelgrass is manifested is the other species of vascular plants intruding into areas formerly dominated almost exclusively by the eelgrass.

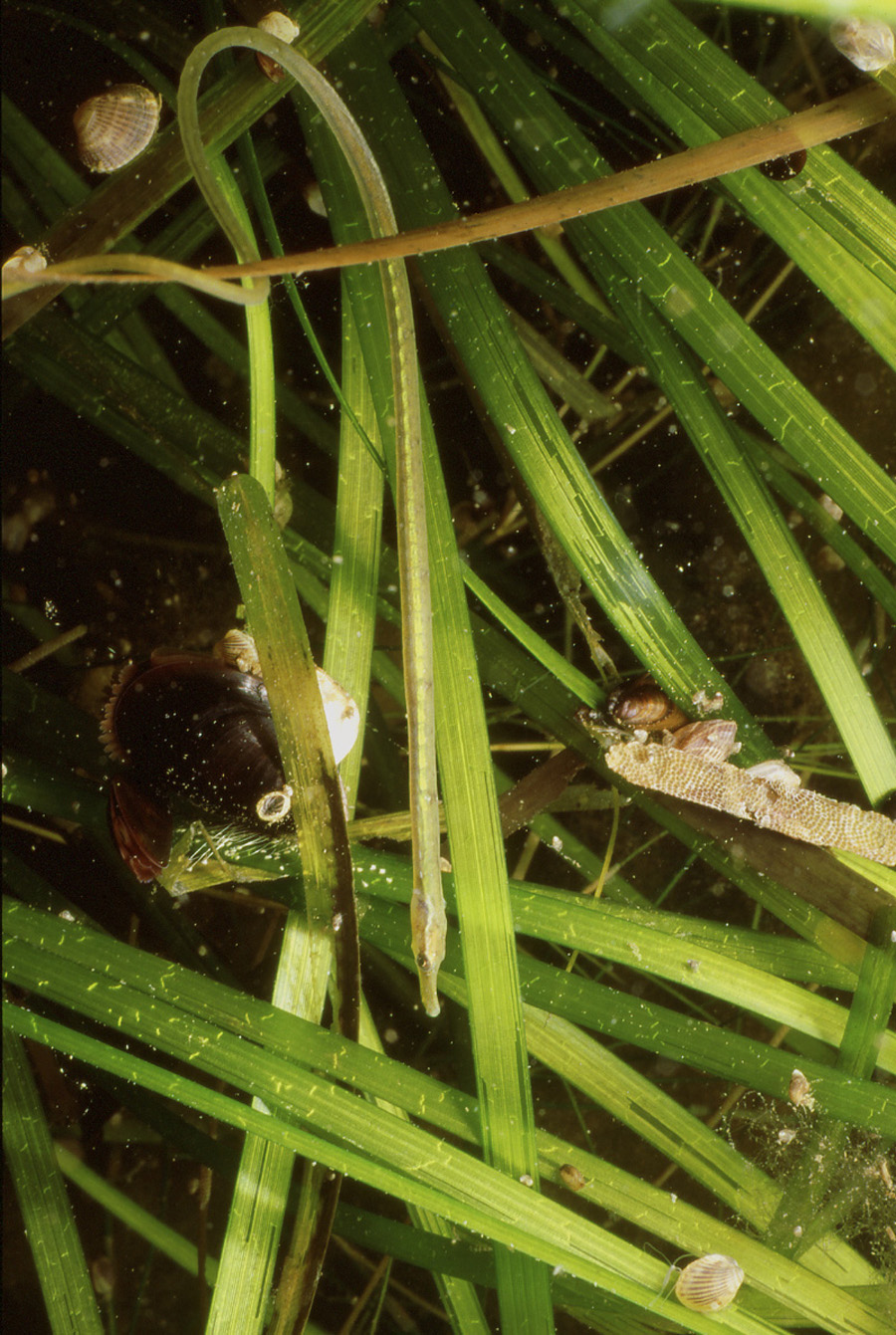

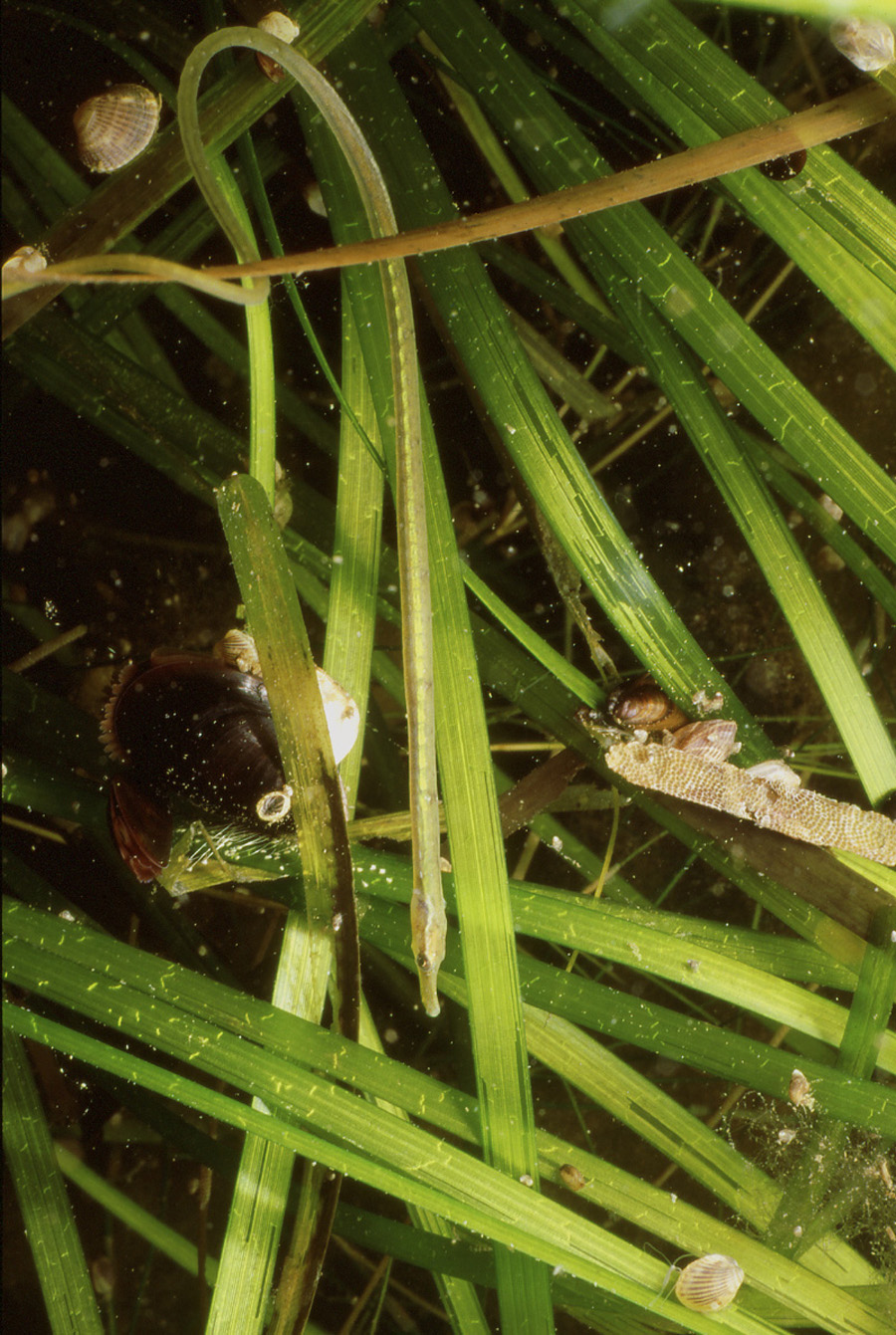

When the eelgrass vegetation has settled down, it offers shelter for a number of small sessile and motile animals. For the sessiles living longest the life span of the eelgrass is still short.

Whether standing among or hanging from, the straight-nosed pipe fishes are like created for the life in the eelgrass.

A nudibranch Embletonia pallida is taking a free ride on a straight-nose. With the pipefishes hanging around in the eel grass and sea slugs being present in great numbers anything can happen but this is by no means a common occurrence.

The broad-nosed pipefish and the perch, here in form of its eggs, are frequent visitors into the eel grass vegetation, the Homo sapiens less so. It can be that the sandy bottoms are readily available for research but, to get the deep burrowing animals included in any single sample, digging deep enough can present certain difficulties.

previous chapter

next chapter

|