9. WHERE ARE THEY FROM

As none of the Baltic species are endemic, they each come from a source of their own. With a connection to the oceans via the Öresund strait the maritime origin is the most obvious of the alternatives. Almost as natural is receiving species from the lakes, via rivers running into the Baltic basin. The human influence in transporting species from far-away water areas is common knowledge nowadays because of the increased threat it poses worldwide. Perhaps the least obvious source are the so-called glacial relicts, in other words, species from lakes formed by the melting waters of the retreating continental ice.

But recent studies based on the use of DNA analysis have caused at least a minor upheaval in the way we have been thinking about the borders between species. Even an established species like the blue mussel, which was always thought to be Mytilus edulis, in other words the same as the one on the western coasts of Scandinavia, has turned out to be Mytilus trossulus. Why is it that the nearest of its kin are found as far away as on the eastern coast of North America? Even though the details of the M. trossulus in the Baltic are still not clear, this puts the earlier studies based on the conventional assumption to a new light, to say the least.

Also, the glacial mysid species Mysis relicta is now thought to be two species in the Baltic alone, with a third, isolated one in Lake Pulmanki. It’s typical of the Baltic that the relict mysid has a counterpart, Mysis mixta, from the oceans. The three species co-inhabit the sea, spread out according to their ability to live in a certain salinity, with only two of them being present at any single location.

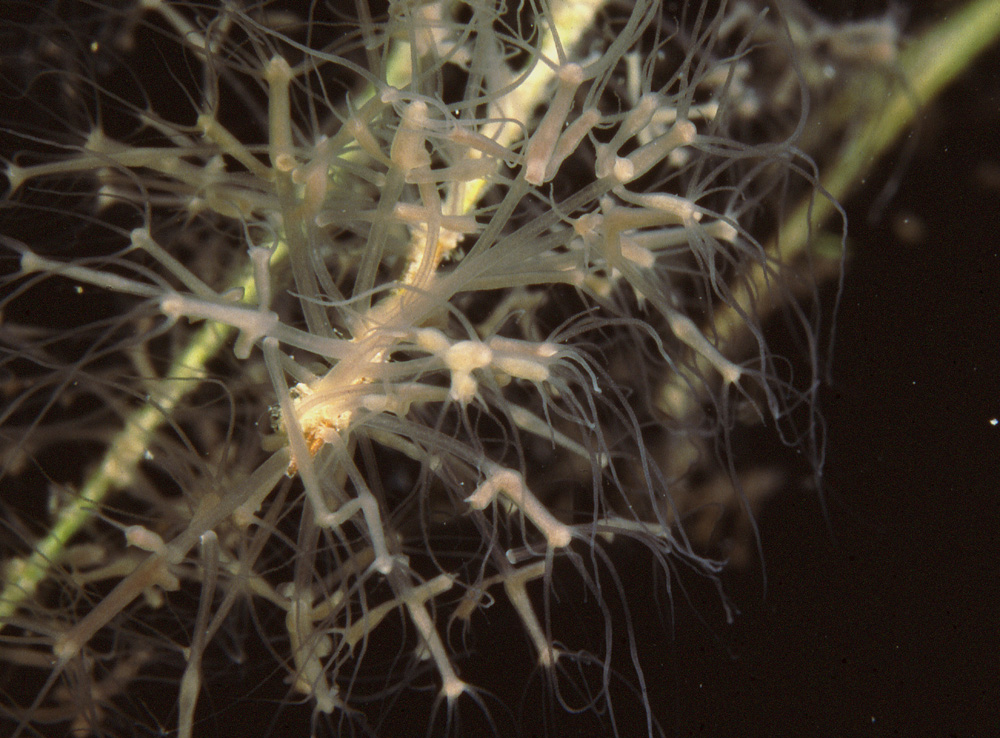

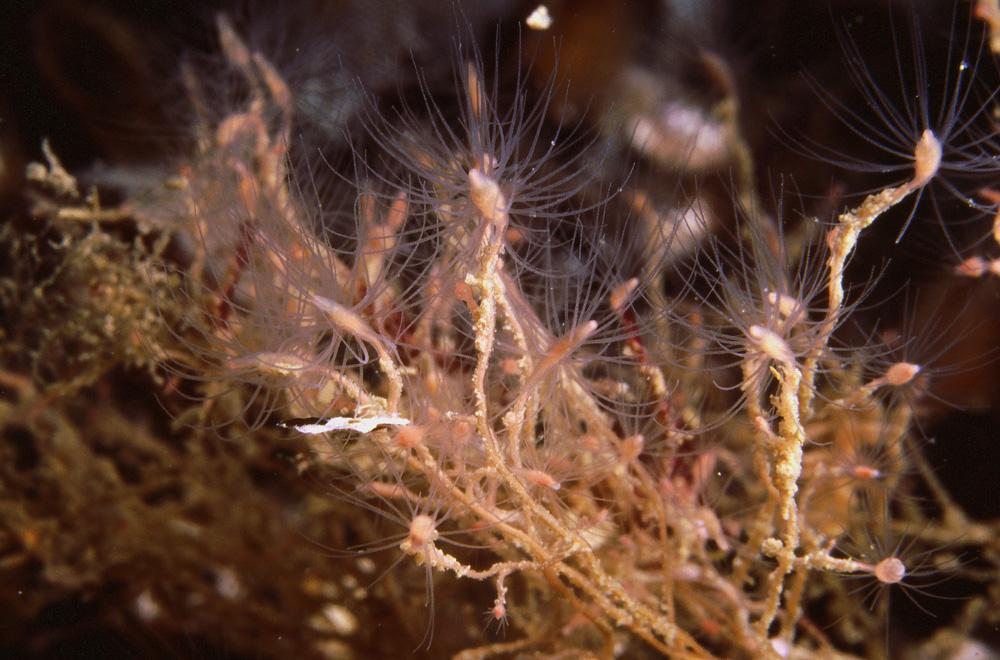

The colonial hydrozoan Cordylophora caspia is often given as an example of an early brackish immigrant and the barnacle Balanus improvisus as a marine one. The inflow of animal species continues at an ever-increasing pace, it seems. One of the recent immigrants, the mysid shrimp Hemimysis anomala, is an example of an apparently successful but harmless one. Its background is yet another example of the ways in which man influences her surroundings: this mysid has spread out of the cultivations of the Soviet era. It was once planted in lakes as food for fish but, having reached the Baltic in a yet unknown method, it is expected to spread out into the whole range of salinities of the basin.

Even with her limited diversity the Baltic can still take you by surprise. The lagoon cockle was, until quite recently, thought of as being one of the four species of bivalves in the Finnish waters. The zebra mussel was discovered at the eastern end of the Gulf of Finland in the nineties but seems to be still limited to a low salinity only. It’s not known how long another bivalve species Parvicardium hauniense has inhabited these parts of the sea but it’s likely that for decades already. Its secret is that it resembles the lagoon cockle quite a bit but, unlike this other cockle, does not grow larger than to a millimeter size.

Two freshwater animal species of the Baltic: the polyp of genus Pelmatohydra and, in the second photo, the shell of genus Lymnaea, being followed by another freshwater shell Theodoxus and ridden on by a seawater shell Hydrobia.

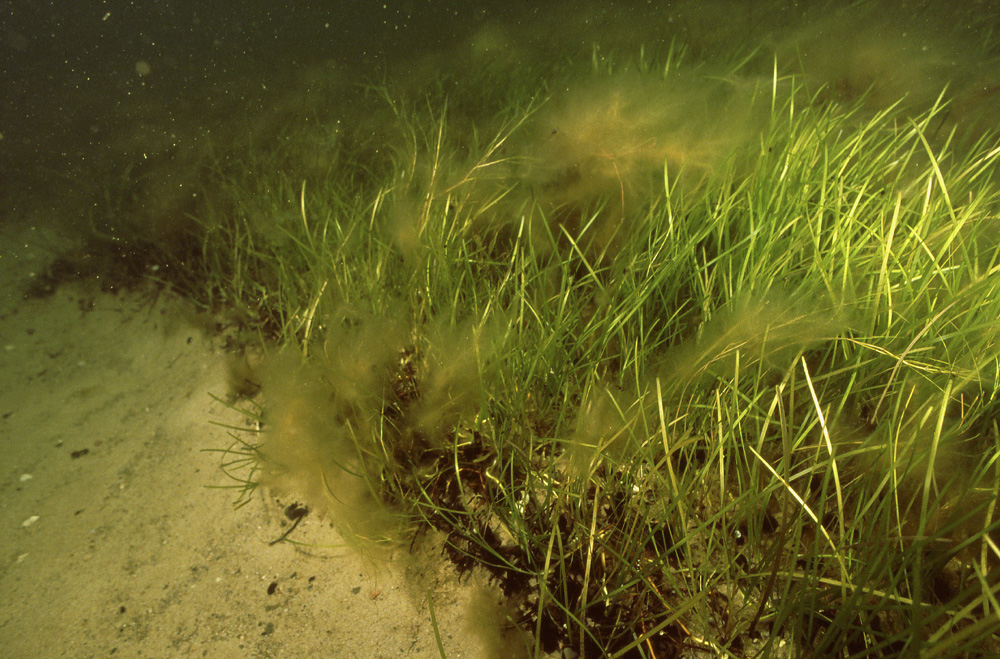

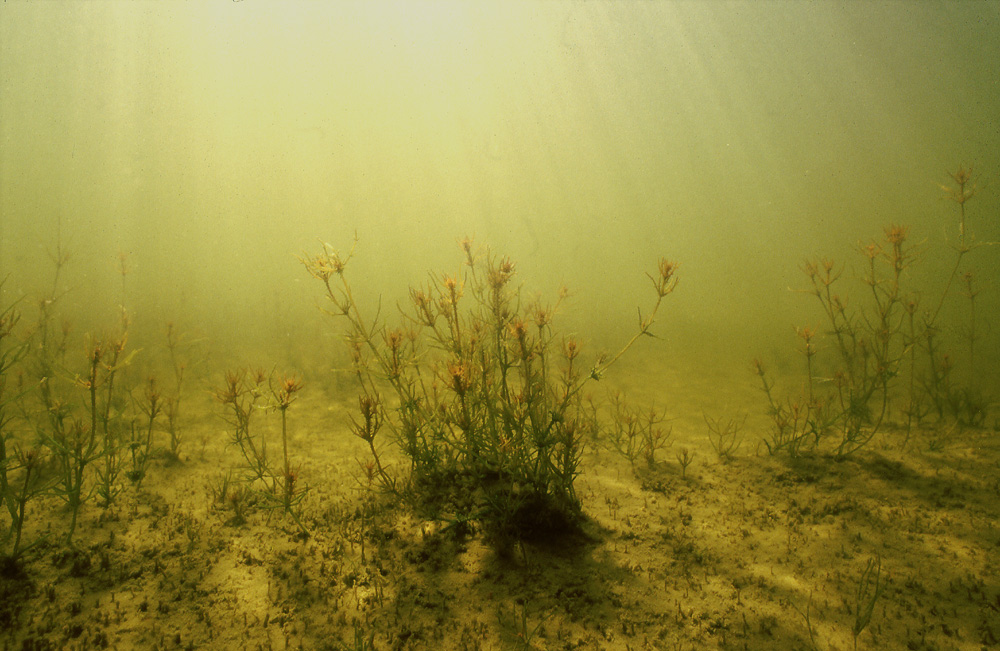

Usually, the vascular plants come from lakes and algae from the sea. In case of the globally dominating true marine plant, Zostera marina and the alga Chara tomentosa, of course, the roles are reversed.

The glacial relicts are out of nature bottom-loving since that’s what they have been used to: cold water. In case of the isopod Saduria entomon it’s a general habit and for the mysid shrimp Mysis mixta a lake deep enough to offer cold water all year round is a requirement for freshwater life. When living in the sea the mysid is pelagic most of the year and visits the coastal waters in autumn for spawning.

Truly brackish species are rare worldwide, as the brackishness is either a geologically speaking short-lived or locally limited phenomenon. Of these two the colonial hydrozoan Cordylophora caspia is from a the Pontocaspian region but the three-spined stickleback is almost a cosmopolitan species with a capability to live in lakes as well as the coastal waters of the oceans.

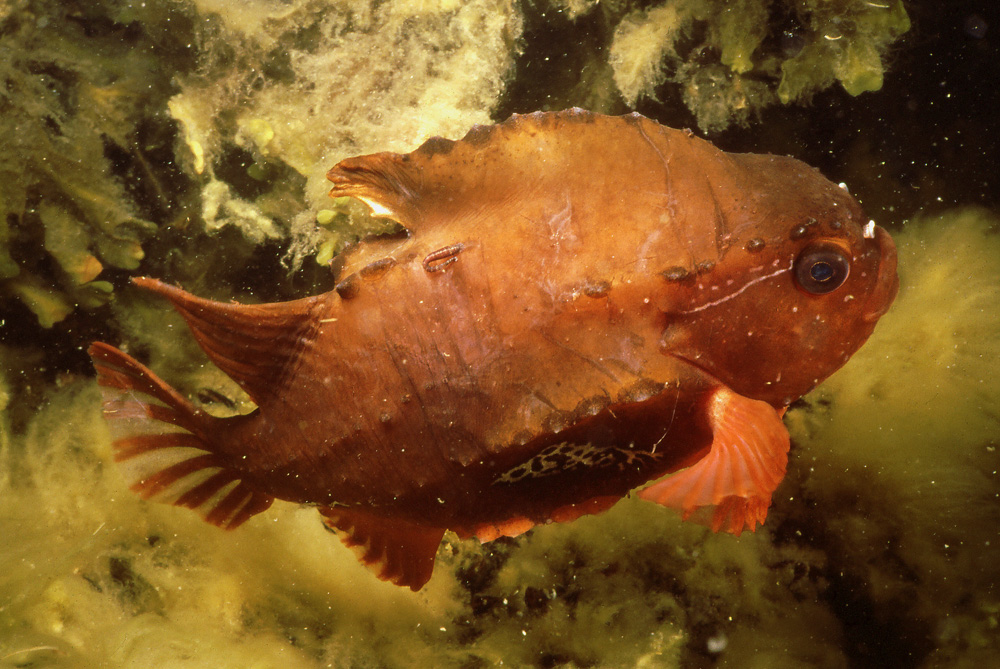

For fishes, immigrating into the Baltic is primarily a question of tolerating the lower salinity. For the lumpfish and bull rout this does not seem to be a problem.

The secret behind the sessile animals also spreading into the relatively young sea area of the Baltic basin is in their method of producing free-swimming larval offspring. The barnacle Balanus improvisus had to cross the Atlantic with the help of man, though, before settling in the Baltic and for the Mytilus trossulus we still need an explanation why its nearest relatives are on the east coast of North America.

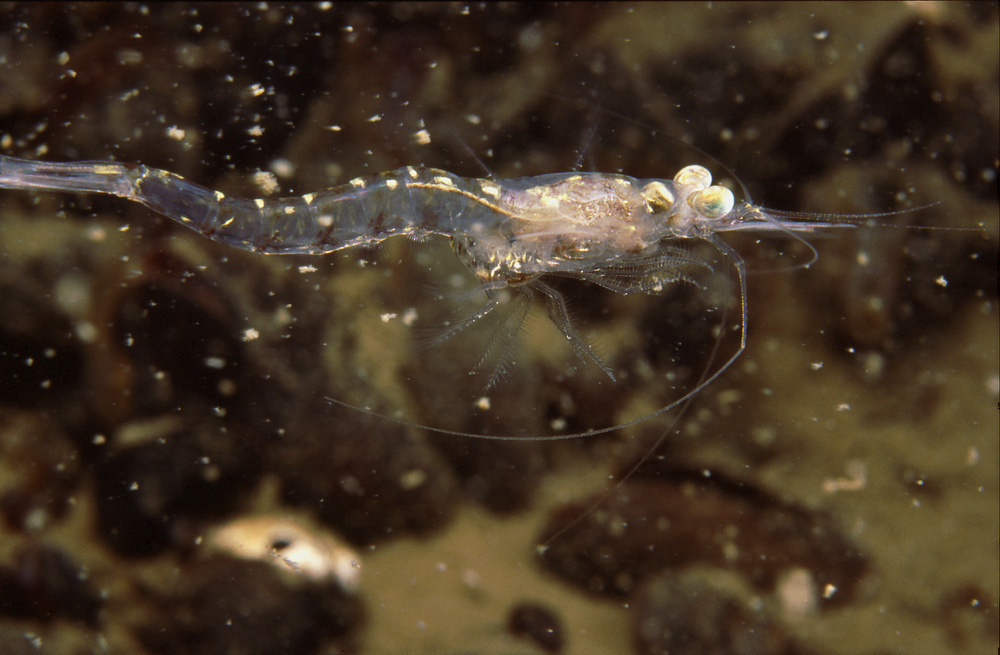

Most of the mysid shrimps of the northern Baltic proper are of marine origin. Mysis mixta is mostly pelagic and Neomysis integer almost its complete opposite, a species that is usually only noticed when staying near the shoreline in huge schools.

Not so long ago we thought that there was just one cockle in the coastal waters of Finland. We don’t really know for how long the other cockle Parvicardium hauniense has been living around because it resembles the young Cerastoderma glaucum a lot and grows to a size of millimeters only. The parvicardium, in the first photo, when looked at from the side, is more asymmetric, while the cerastoderma, in the second photo, is more of a coffin shape. When older and burying into the soft bottom the cerastoderma, in the third photo, can no longer be confused with the parvicardium.

Would you like to have a guess at these cockles living on the eelgrass? Mine is that quite a few of them are parvicardiums, but perhaps the cerastodermas are still the majority. One of the ways in which the parvicardium reveals itself could well be its bigger motility: it will use its foot more often to move around the vegetation it lives on.

Enter the mysidskaya rossiya. The species was identified out of a sample collected in 1993 but my first photo of it is from 1992. It’s a proof of my biological innocence in those days that I was thinking of taking a photo of fish fry, when in fact it was juvenile mysids of the species Hemimysis anomala. Taking the second photo I already knew what the little dots in the shade of a small crevice meant.

The red mysids really caught my attention during a night dive as a lively mass of rapidly moving red dots, their large eyes reflecting the light of the dive lamp. The red color, large stationary swarms during the day and individuals moving around in the proximity of crevices in search of food at night are all unmistakable characteristics of this species.

A runaway offspring of Soviet fish food farming, the Hemimysis has, fortunately, proved to be a welcome addition rather than a threat for the resident species. It is a powerful swimmer but if even that is not enough to keep it out of the harm’s way, it can always jump into the hyperspace!

|

Lisää pääkuvan päälle tekstiä klikkaamalla ratas-ikonia,

joka ilmestyy tuodessasi hiiren tämän tekstin päälle.